Vans has scored a preliminary win in its trademark fight against Walmart. In an order dated March 31, a California federal court has granted Vans’ motion for a preliminary injunction, ordering Walmart to refrain from making, marketing, and selling footwear that bears Vans’ trademarks, including almost 30 allegedly infringing shoe styles that it has offered up in the past for the duration of the case. On order comes on the heels of Vans filing suit against Walmart late last year, arguing that the retail titan has embarked on “an escalating campaign to knock off virtually all of [its] bestselling shoes,” and is running afoul of its trademark rights in the process.

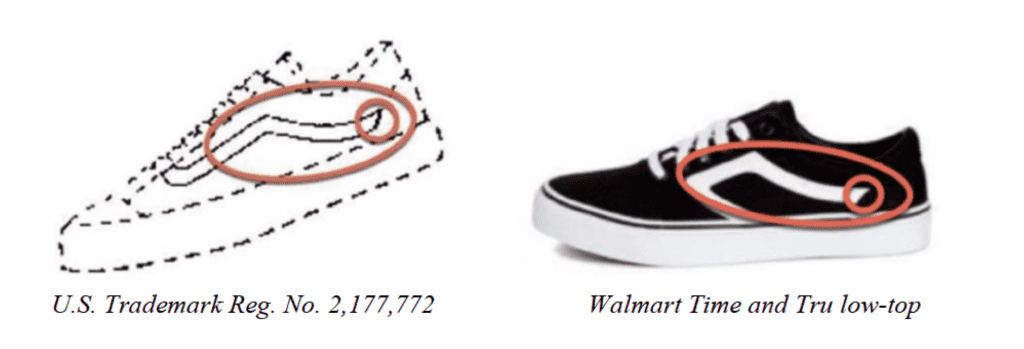

In the newly-issued order, Judge David Carter of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California sets out Vans’ allegations, namely that “each of Walmart’s infringing shoes uses a ‘knockoff’ of Vans’ registered side stripe trademark,” “each of Walmart’s infringing low-top shoes copies Vans’ registered stitching mark,” more than a dozen Walmart’s “knockoff versions of Vans’ Old Skool shoes imitate every element of the Old Skool trade dress,” each of Walmart’s high-top knockoff shoes “imitate every element of the SK8-Hi trade dress,” and Walmart’s Wonder Nation toddler shoe “imitates every element of the Old Skool Toddler trade dress.”

Reflecting on such alleged infringements in connection with Vans’ quest for a preliminary injunction, the court first considered whether Vans’ trademark and trade dress rights are valid and protectable. “Walmart does not dispute that Vans holds incontestable United States trademark registrations for its Side Stripe Mark and its Stitching Mark,” Judge Carter states, noting that the court accordingly “finds that both the Side Stripe Mark and the Stitching Mark are valid and enforceable trademarks and moves on to consider whether Vans’ unregistered trade dress rights are valid and enforceable under the Lanham Act.”

In terms of the Old Skool, Old Skool Toddler, and SK8-Hi trade dresses, Judge Carter states that Vans is likely to succeed in showing that they have acquired secondary meaning. The court states that Vans presented evidence of “extensive and longstanding use of the designs, significant expenditures to advertise the shoes, and considerable sales and revenues of the shoes.”

Specifically, Vans provided “testimony asserting that it has continuously and exclusively used” the trade dress; has spent “tens of millions of dollars advertising the shoes in both traditional and online media;” has generated revenues of more than $16 billion in the U.S., alone, from sales of footwear bearing the trade dress; and has provided secondary meaning survey evidence that purchasers associate the Old Skool and SK8-Hi designs with Vans. (Vans’ surveys found a net secondary meaning level of 39.4% for each of the designs, which the court found “falls within the range that courts have found to be sufficient to support secondary meaning,” and thereby, “corroborates Vans’ argument” about secondary meaning.)

Taken together, Judge Carter states that Vans’ “considerable promotional expenditures, sales, and revenues are evidence of the secondary meaning of the Old Skool, Old Skool Toddler, and SK8-Hi trade dresses.”

“Having determined that Vans is likely to succeed in showing that its trademarks and trade dresses are valid and protectable,” the Court turned its attention to whether a “‘reasonably prudent consumer’ in the marketplace is likely to be confused about the origin of the good or service bearing one of the marks.” A consideration of the Sleekcraft factors weighed in Vans’ favor here. For instance, the court found that the shoes that Walmart has offered up are, in fact, similar to Vans, “the parties’ shoes are in proximity to each other,” and the “typical purchasers of athletic shoes are ‘unlikely to exercise a high degree of care in selecting shoes.’” Moreover, the court determined that despite pushback from Walmart about the admissibility of consumer commentary about the Walmart sneakers, social media comments and posts on Walmart’s website that appear to demonstrate actual confusion, “move the needle slightly in Vans’ favor.”

The only factor that does not apply here, according to Judge Carter, is the use of similar marketing channels given that Vans is arguing only post-sale confusion, and “courts have held that the marketing channel factor is directed toward pre-sale confusion and is therefore ‘immaterial to the issue whether actionable confusion is likely to occur after the marked product has entered the public arena.’”

As for the critical element of irreparable harm, which Walmart previously argued is not at play here, as Vans is not losing sales and its reputation is not being diminished as a result of Walmart’s footwear, the court sided with Vans, holding that “Vans’ evidence of loss of market control, consumer confusion, and the poor quality of Walmart’s shoes is sufficient to establish that [it] is likely to suffer irreparable harm absent injunctive relief.”

With the foregoing in mind, the court ordered that Walmart refrain from “using Vans’ Side Stripe Mark, Old Skool trade dress, SK8-Hi trade dress, Old Skool Toddler trade dress (each as defined in Vans’ Complaint in this action), or any of Vans’ registered trademarks, or any trade dress or trademark that is substantially similar thereto, on or in connection with [its] shoes or related services” for the duration of the litigation.

The case is Vans, Inc. et al, v. Walmart, Inc., et al, 8:21-cv-01876 (C.D.Cal.)