The law is creeping on to the runway. We saw it in February, when Gucci tapped Brooklyn-based artist GucciGhost to put his mark on its garments and accessories. One of the bags from the Italian design house’s Fall/Winter 2016 bears a graffiti-tagged “REAL” situated just above a Gucci logo. On a jacket, the © symbol, which denotes a federal copyright registration. Another includes an ®, the equivalent trademark notation.

Skip forward to the Spring/Summer 2017 shows, which saw Dolce & Gabbana bring legal commentary to the runway. No, the design duo was not looking to shed light on their long-running (and not now concluded) tax evasion trials, but instead the vast market for designer knockoffs and counterfeits. As the Wall Street Journal’s Christina Binkley noted in connection with the brand’s “Dolce & Gabbaba”, “Docce & Gabbinetti” and other slightly off-kilter tees, “Dolce & Gabbana is having a laugh at knockoffs. The tees will be affordable to GenZs, I assume.”

Virgil Abloh, the creative behind Off-White, unveiled a makeshift Canal Street set up outside of his Spring/Summer 2017 show venue in Paris on Thursday evening, offering fake fake (aka real) Off-White bags, which will also go on sale tomorrow at Colette. The stunt fit neatly within the brand’s image this season, having revealed: “Off-White™ first ever ‘if the cops come run’ handbag campaign” earlier this month (pictured below).

A comment on the excessive amounts of fake Off-White garments and bags – many bearing the brand’s striped logo and “White” trademark – that have consistently been offered on e-commerce marketplaces like Alibaba and eBay for years now? Maybe implicitly. But according to the brand, it was more a statement on the “see now buy now” trend.

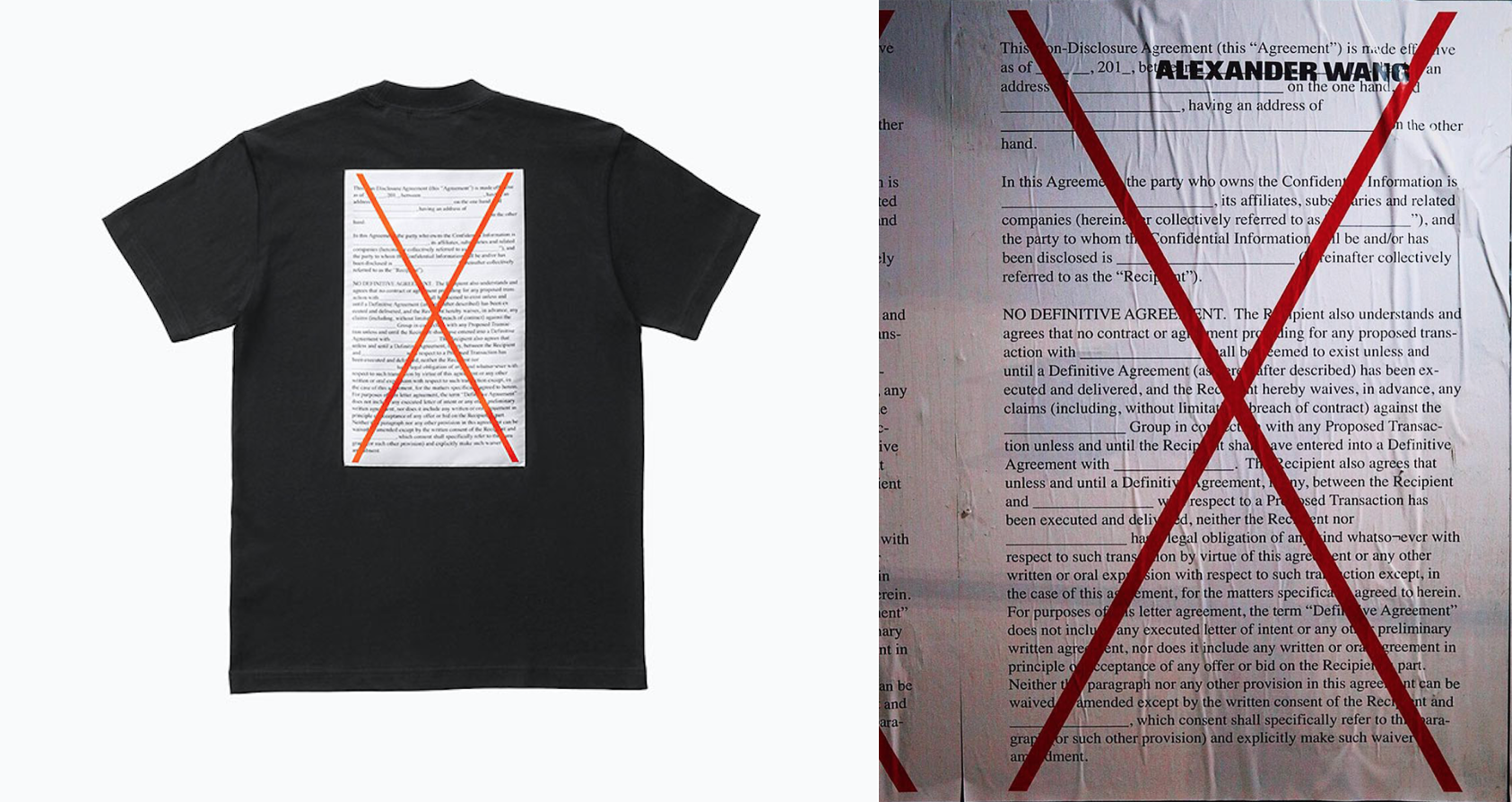

Earlier this month, we saw Alexander Wang printing copyright infringement correspondences with adidas on sweatshirts as part of his recently unveiled collaboration with the German sportswear giant. Blank non-disclosure agreements – which were presumably used between Wang and adidas – also found their way onto garments for the collection.

Pyer Moss, the New York-based brand headed up by Kirby Jean-Raymond, also took the legal route, embroidering “Please speak only to my attorney” on a purple satin jacket. On a turtleneck, he displayed the front page of a mock summons (the legal document that formally initiates a lawsuit), which reads “Greedy Asshole vs. Guad, LLC and Kirby Jean-Raymond.” This is in reference to the ugly lawsuit that Jean-Raymond’s former business partner, Rayon Baker, filed against him early this year, accusing him of an array of claims, including trademark infringement, fraud, breach of contract and unfair competition. That lawsuit is still ongoing.

The rise in visibility of brands’ legal battles is not just taking place on the runway, though. In fact, it is likely just a secondary reaction to a larger trend in the industry. While legal action has certainly always been prevalent in the fashion industry, just as in any other line of business, over the past several years, in particular, designers’ legal battles have become increasingly public. This is likely due to the instantaneous sharing of information online and on social media, and the widespread availability in downright accurate counterfeits, which was certainly on Gucci’s mind in connection with its Fall/Winter 2016 show and Abloh’s this season.

Maybe more significant, though, is the fact that the names behind many of the industry’s fashion brands are not just names anymore. Hardly behind-the-scenes forces, many creative directors and designers, alike, have become celebrities in their own right (another phenomenon that has come about in large part thanks to social media). With this in mind, much like it is “cultural news” when a celebrity is jailed or sued for any array of legal infractions, when a designer or creative direction or a design house in general is embroiled in a legal scuffle, it garners attention from the media, fashion fans and industry insiders.

You may recall the much-buzzed-about Christian Louboutin vs. Yves Saint Laurent legal showdown, which Louboutin initiated against YSL in New York federal court in 2011 after YSL began offering red-soled shoes for sale. (Louboutin maintains a federally registered trademark for its famed red soles). That lawsuit became a topic of conversation for legal scholars and fashion industry writers, alike, and to an extent, it set the stage – in terms of the growing interest among the general public – for many intellectual property and non-intellectual property lawsuits to come.

Other intellectual property battles have been lodged against Jeremy Scott, who was sued, together with Moschino, last summer, for copying graffiti artist RIME’s work and putting it on a dress for the Italian design house’s F/W 2015 collection. And seemingly aggressive (and in the eyes of most laypeople, unnecessary) trademark suits have been filed by a number of big designs houses, such as Chanel, against individuals for using the brands’ names in connection with their own businesses. Such lawsuit have been initiated – and won – even when those individuals’ birth names contain the brands’ names. You may remember one such suit that Chanel filed against Chanel Jones and her business, Chanel’s Salon. The Paris-based design house won that lawsuit and Jones was forced to rebrand.

More personal matters, such as John Galliano’s wrongful termination case against Christian Dior, following his ouster in 2011, have also proven quite attention-grabbing. After being banished from his roles as creative director for Christian Dior and LVMH-owned John Galliano following a drunken rant caught on tape, which involved anti-Semitic remarks, the industry icon filed suit against LVMH, seeking $18 million in damages.

The same can be said of the lawsuit that Balenciaga’s parent company, Kering, initiated against its former creative director Nicolas Ghesquière in 2013, alleging that Ghesquière breached his contract, particularly the agreement to refrain from making statements that could undermine the image of Balenciaga or its parent company. The lawsuit stemmed from a string of comments he made to London-based fashion magazine System.

And lest we forget the dueling lawsuits between Nike and three of its former upper-level employees, Marc Dolce (formerly Nike’s Global Design Director), Mark Miner (who was the Senior Global Footwear Designer at Nike), and Denis Dekovic (its former senior design director), who allegedly stole millions of dollars of confidential information before joining rival adidas AG. That lawsuit has since been settled, and the three men have begun work for adidas.

With fashion – and thus, the runway – serving to reflect the state of the world around it, the influx of legal-centric commentary by way of garment designs should come as little surprise. As fashion has become increasingly corporatized – largely thanks to the acquisition activities of conglomerates like Kering and LVMH beginning in the 1980’s – art and commerce arguably observe less of an even balance than they did when brands were small time affairs.

But most of today’s mainstream designers are not building small brands. They are competing in the global marketplace (thanks, in large part, to e-commerce and the instantaneous connectivity afforded by social media). The Alexander Wangs of the world are operating multi-national companies that manufacture fully fleshed out collections of garments and accessories. This is a far cry from focusing on a single aspect of the consumer’s wardrobe, which was a popular tactic not too, too many decades ago. Ralph Lauren did ties. Louis Vuitton produced leather goods. Hermès was known for its saddlery. Brioni for its suits, and Berluti for its footwear.

What was once the norm – small companies focused on individual wardrobe elements, which were largely shielded from the ugly lawsuits of the corporate world – has turned into international brands. As a result, brand owners are engaged in (and subject to) many of the same business and legal exercises as just about every other type of major company on the market – those companies just do not have bi-annual runway shows in which they can artfully display their comments on legality.