From Tiffany & Co. and LVMH’s much-anticipated merger and the rival lawsuits that came with it to L Brands, and Sycamore Partners’ $525 million deal for lingerie giant Victoria’s Secret, and the resulting string of since-settled cases tied to that acquisition, which ultimately never came to be, to VF Corp.’s acquisition of Supreme, the $1.1 billion Farfetch “mega deal,” and Ferrari majority owner Exor’s snap-up of Chinese luxury brand Shang Xia from Hermès, 2020 was filled with headline-making M&A transactions and legal actions in connection with those acquisitions, as well as previously-negotiated deals, much of which was complicated – or at least, more nuanced – as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Here is a look at some of the most noteworthy deals and M&A-related legal battles of 2020 …

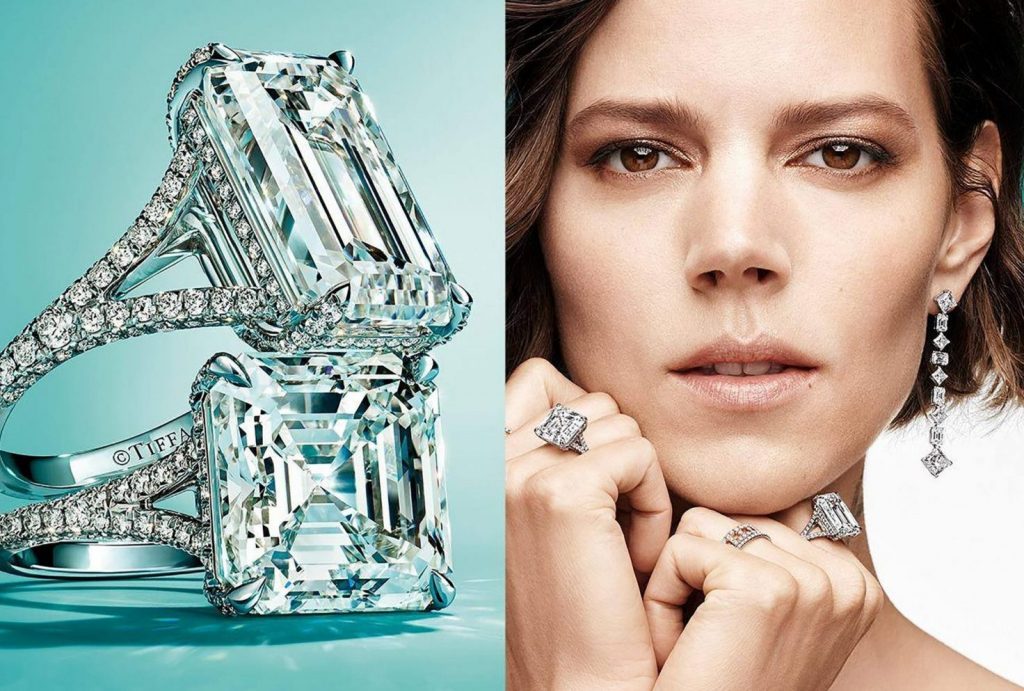

1. LVMH, Tiffany Reach New $15.8 Billion Deal, Agree to Settle Legal Dispute

LVMH and Tiffany & Co. managed to salvage their multi-billion dollar acquisition deal in late October. In a statement on October 29, the parties confirmed that LVMH will pay $131.5 per Tiffany share, down from the $135/share price tag they initially agreed to in November 2019 before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a whole, the deal amounts to a whopping $15.8 billion merger.

In announcing the new merger terms, the French luxury goods conglomerate and the New York-based jewelry company revealed that they had settled the bitter legal dispute that Tiffany & Co. initiated in a Delaware court this fall. LVMH’s attempt to back out of the initial $16.2 billion deal swiftly prompted Tiffany to file suit, seeking an order from a Delaware Chancery Court judge requiring LVMH to “abide by its contractual obligation under the merger agreement to complete the transaction on the agreed terms.”

LVMH responded by threatening litigation of its own on the grounds that its board “had the opportunity to examine the current economic situation of Tiffany and its “first half results and perspectives for 2020 are very disappointing, and significantly inferior to those of comparable LVMH Group [brands] during this period.” In the complaint that it did eventually file, LVMH argued, among other things, that Tiffany “hemorrhaged cash for the first time in a quarter century, with no end to its problems in sight,” and asserted that “Tiffany’s performance will continue to be poor.” With that in mind, and given “the decision by two sophisticated parties, represented by sophisticated advisers, to omit a pandemic carve,” LVMH stated the pandemic has, in fact, “caused a material adverse effect that allows LVMH to terminate.”

2. Farfetch’s $1.1 Billion Deal with Richemont, Alibaba Exemplifies Some Existing Trends in Luxury

A $1.15 billion deal between Cartier’s parent company Richemont, Chinese e-commerce titan Alibaba, and fashion retail platform Farfetch was big news in the luxury market this year. In a statement in early November, Swiss conglomerate Richemont and Alibaba revealed that they will invest a total of $1.1 billion in Farfetch and its new venture specifically tailored to the Chinese market, confirming rumors that a mega-deal was in the making. Meanwhile, Artemis – an investment vehicle tied to Gucci owner Kering – simultaneously announced that it would increase its stake in Farfetch with a $50 million injection of cash in exchange for Farfetch’s Class A ordinary shares.

Beyond the focus on China, the headline-making deal plays to two existing but ever-accelerating trends in fashion/luxury in light of the COVID-19 pandemic: the rampant adoption of e-commerce by notoriously digitally-averse high fashion and luxury brands, and an enduring consolidation of players in the upper echelon of the industry.

The deal appears to play into the larger fortification-but-consolidation trend underway, which as the Financial Times wrote last year, has enabled “LVMH, Kering and Richemont [to] all grow through acquisitions while smaller players have sought the security of bigger groups, such as Versace, which was sold to Michael Kors, now Capri Holdings, for $2 billion in late 2018.”

Given the rising investments of these industry titans when it comes to e-commerce sales and the costs associated with perfecting the digital consumer experience, more generally, buy-outs by big players are expected to continue throughout 2021. The WSJ’s Carol Ryan points to “underperforming listed brands like Tod’s, or those still in founders’ hands, such as shoemaker Christian Louboutin,” as potential targets.

3. Vans’ Parent Company VF Corp. Buying Streetwear Brand Supreme in $2.1 Billion Deal

Supreme has a new owner. Three years after selling off a reported 50 percent stake to private equity giant Carlyle Group, VF Corp revealed on November 9 that it would pay $2.1 billion to buy popular streetwear brand. Denver, Colorado-headquartered VF Corp – which owns a number of brands, including Vans, The North Face, Eastpak, and Timberland – said it would make “an additional payment of up to $300 million subject to satisfaction of certain post-closing milestones.”

The headline-making deal will see VF Corp. take full ownership of Supreme, with current Supreme investors Carlyle Group and New York-based private equity firm Goode Partners agreeing to sell their stakes in the New York-based brand that American-British businessman James Jebbia founded in 1994 and catapulted to streetwear success over the past two decades thanks to its meticulously-crafted strategy of dropping limited edition wares, many of which are branded with Supreme’s name and red-and-white box logo, branding that has found significant fame and no shortage of infringement across the globe.

The key question from the time of the Carlyle cash injection remains in play, particularly in light of chatter about aggressive expansion: Can Supreme be cool and corporate at the same time?

4. Ferrari Majority Stakeholder Will Acquire Hermès-Owned Shang Xia in China-Focused Move

In a release from Exor early this month, the holding company revealed that it will invest “around €80 million [$96.9 million] in Shang Xia via a reserved capital increase that will result in it becoming the company’s majority shareholder.” Exor noted that Hermès – which “has accompanied Shang Xia successfully throughout the initial phase of its development – will remain as an important shareholder alongside Exor and [founder] Jiang Qiong Er.”

The pairing between Hermès and Exor by way of Shang Xia – whose array of upscale home goods, silk scarves, streamlined leather goods, and refined apparel offerings are not a terribly far cry from those of Hermès – is certainly an interesting one. While Exor is not known for its holdings in the fashion industry, it is, nonetheless, well equipped in the luxury space, as a leading shareholder in Ferrari, where Exor chairman and CEO John Elkann holds the chairman role.

Exor’s sweeping stake in Ferrari – which as of 2015 sees it maintain a total voting power of nearly 50 percent with Piero Ferrari, son of the Italian automaker’s founder Enzo Ferrari – speaks to its might in the luxury market. It also sheds light on a number of noteworthy commonalities between Hermès and Ferrari, given that Ferrari is far more a luxury entity in the business of employing luxury manufacturing, marketing, and distribution methods than a traditional automaker.

5. There’s More to it Than Market Share, What the FTC’s Quest to Block Billie-P&G Merger Means for DTC Buy-Outs

On the heels of P&G and Billie revealing that they had reached an M&A deal in January 2020, the Federal Trade Commission swooped in to call foul. The basis for its action: The acquisition would “eliminate substantial and growing head-to-head competition” between Cincinnati, Ohio-based P&G – “the market-leading supplier of both women’s and men’s wet shave razors” – and “nascent competitor Billie” in U.S. wet shave razor markets.

The FTC’s move to halt the Billie acquisition is not the first of its kind this year. In fact, the government agency filed an administrative complaint in February, in which it asserted that it had “reason to believe that Edgewell Personal Care Company and Harry’s, Inc. have executed a merger agreement in violation of [various sections] of the FTC Act,” as well as the Clayton Antitrust Act. As it turns out, Edgewell, the shaving company that owns a stable of household names from Playtex and Skintimate to shaving brands Schick Edge and Wilkinson Sword, had made Harry’s a $1.37 billion dollar offer, and the burgeoning direct-to-consumer shaving company took it.

The striking aspect of the FTC’s recent DTC shaving company-centric activity: it appears to go against the fact that antitrust agencies “traditionally consider current competition between merging parties and look to their existing market shares as indicators of competitive strength” in order to determine if anticompetition concerns are potentially afoot. The larger the market shares at play, the more likely there will be FTC pushback on the basis of competition, and thus, small share gains – such as 2.5 percent – have largely fallen outside of the realm of FTC action.

Yet, Billie and Harry’s – both of which relatively small when it comes to market share – caught the FTC’s attention, nonetheless, since “for several years, the federal antitrust agencies, particularly the FTC, have been developing a concept known as ‘nascent competition.’” In other words, the agency has been opposing instances in which the acquisition target is a small, but rapidly growing entity – or “disruptive” competitor of a larger, dominant company.

6. A $1.1 Billion Brand, 3 Lawsuits and COVID-19: The Breakdown of the $525 Million Victoria’s Secret Deal

As of this spring, a major deal was up in the air in the midst of turmoil in the COVID-19 retail landscape: Sycamore Partners’ $525 million proffer for Victoria’s Secret. After signing off on a deal in late February to acquire 55 percent of Victoria’s Secret from its parent company L Brands, Sycamore wanted out, and it pointed to the global health pandemic – and the ailing lingerie giant’s response to it – as its basis for attempting to retract on the deal.

A string of since-settled lawsuits between the two parties got its start on April 22 when Sycamore filed suit against L Brands in a Delaware Chancery court, arguing that while the retail group was legally “required to operate the Victoria’s Secret business in the ordinary course consistent with past practice” until the deal closed (which was slated for the second quarter of this year), it failed to uphold its end of the bargain when it “decided to close the lingerie brand’s U.S. stores, furlough the majority of its workers, and skip April rent payments.”

More than that, counsel for Sycamore – which sought the court’s blessing to terminate on the deal that valued Victoria’s Secret at $1.1 billion – asserted that the onset of the “extraordinary” COVID-19 crisis brought an MAE clause in the parties’ agreement into effect, thereby, enabling it to walk away from the deal without incurring a steep penalty.

L Brands responded to Sycamore’s complaint with a lawsuit of its own on April 23, asking the same court to uphold the terms of the deal on the basis that “Sycamore’s current position is pure gamesmanship,” and “its invalid and improper termination” amounted to little more than a quest to scoop up the Victoria’s Secret brand for less than the formerly-agreed upon price.

And seemingly attempting to double-down in light of the potential weakness in its initial suit thanks to the pandemic exception, Sycamore filed a second complaint on April 24, arguing that if the parties’ deal was not already off the table, L Brand’s countersuit has formally “invalidated the financing that [Sycamore] had lined up” to acquire the company.

The parties revealed that they had formally called off the deal, and settled their rival lawsuits by early May.

7. Why Two Retail Giants Are Buying Distressed Mall Brands Out of Bankruptcy

Mall giant Simon Property Group and Authentic Brands Group – the owner and licensor of over 50 well-known brands, ranging from Juicy Couture to Judith Leiber – have been working together over the past few years to buy-up bankrupt companies’ assets (from their real estate but more importantly their intellectual property and large swathes of consumer data), in some cases, at a notably discounted rate – with Barneys, Brooks Brothers, Lucky Brand, and Forever 21 among their targets.

“In the short-term, these acquisitions should prove to be lucrative for both Simon and Authentic Brands,” according to Goulston & Storrs PC attorneys Vanessa Moody and Yara Kass-Gergi. “As a result of [their acquisition of these retailers, Simon – the largest shopping mall operator in America – is able to better control the occupancy rates at its shopping centers, helping to ensure their continued viability,” they note, “while ABG benefits by having its retail business partner also be the landlord of many of its brick and mortar store locations.”

As for their prospects for longer-term success, both for SPARC Group – the joint venture that Simon and ABG launched in early 2020 – and the companies that SPARC is readily taking ownership of, Moody and Kass-Gergi say that is less obvious. “The future impact of COVID-19 on retail, including retailers’ ability to ride out any significant second or third rounds of governmentally mandated store closures, remains entirely uncertain.” As a result, they claim that “any expansion of retail holdings and physical store locations comes with some inherent risk,” including potential issues over “whether SPARC will be able to retain the high quality of the brands it acquires as it continues to acquire more and more companies is another question.”

Additionally, it is worth noting, per Moody and Kass-Gergi, that at least “some competitors and other interested parties are already starting to quietly wonder whether the growing list of retailers under the Simon and Authentic Brands umbrella does or should at some point raise antitrust concerns,” which could prove interesting.

8. Misappropriation by Acquisition: Are M&A Discussions Setting Companies Up for Complicated Lawsuits?

Misappropriation by acquisition cases are having a moment in the fashion/beauty space. On the heels of Olaplex landing a $66 million win in the trade secret suit it filed against L’Oreal in January 2017 (less than a year after the enactment of the federal Defend Trade Secrets Act), in which the haircare startup accused the beauty titan of pilfering confidential information about its products during potential M&A discussions, three similar suits have since been filed. Le Tote sued Urban Outfitters in June, alleging that the company has stolen its trade secret-protected business model under the alleged guise of a potential acquisition in order to create a rival fashion rental business, Nuuly.

Around the very same time, Seed Beauty – the Southern California-based company responsible for “creating, developing, manufacturing, storing, selling, and distributing” the products of the billion dollar beauty ventures of Kim Kardashian and Kylie Jenner – filed two separate trade secret lawsuits: one against Kardashian’s KKW Beauty, and another against Coty, Inc. and Kylie Jenner’s corporate entity, in connection with Coty’s acquisitions of stakes in the half-sisters’ buzzy brands.

In both of its complaints, Seed alleges that as a result of the cutting-edge nature of its business model, the details of its “creative and logistical development services” and the terms of the “exclusive relationships [it has] with its beauty brand partners” amount to “highly sensitive, confidential and trade secret information.” Those “highly sensitive and confidential” elements of its business are at risk, Seed claims, due to Jenner and Kardashian’s respective headline-making deals with Coty, thereby.

The cases present an important look at how trade secret information becomes an issue in the context of acquisitions. While traditionally under-discussed, trade secret misappropriation by acquisition has received increased attention in recent years in light of headline-making matters, such as the since-settled lawsuit between Alphabet’s Waymo and Uber, a case that centered on Uber’s acquisition of self-driving startup Ottomotto.

The currently-ongoing cases also come as part of a larger movement that includes a growing amount of trade secret litigation. As a result of “the digitization of intellectual property and ongoing competition across industries,” as well as an increase in M&A discussions in light of a larger trend towards consolidation, among other macro developments, companies are at elevated risk of trade secret theft, and no small number are responding to such threats and instances of misappropriation by “increasingly engaging in legal proceedings specific to trade secrets.”