Deep Dives

The onset and continued impact of the pandemic has accelerated a range of existing trends within the fashion industry and retail more generally, as we have seen in many instances over the past two years. This includes the increased reliance by consumers on e-commerce and the resulting appetite among even very digitally-hesitant brands to embrace the medium. This has implications for companies from a branding perspective (battles over website trade dress come to mind) and a privacy one, as well, prompting us to ask this year whether fashion industry players are in need of chief privacy officers.

The pandemic has also brought about a heightened awareness of – and emphasis on – sustainability and ESG by consumers and brands, alike, and growing efforts by lawmakers, watchdogs, and plaintiffs, among others, to crackdown on the largely unregulated nature of ESG disclosures and sustainability-centric marketing.

At the same time, in 2021, we witnessed the continuation of the “Great Resignation,” which has seen employees quitting their jobs in the U.S. and other countries, including China; the striking rise of Buy Now, Pay Later financing (and the commencement of corresponding regulator attention); the fashion industry’s adoption of the special purpose acquisition corporation – “SPAC” – as seen in the very recent listing of Zegna; and a slew of retail developments, prompting questions about what a sale in a physical outpost, for instance, really entails in light of the robust role of e-commerce, and whether companies are more valuable when their physical and e-commerce operations are split.

As the year comes to a close, we take a quick look at a few of these trends in order to take the temperature of the retail space and corresponding legal landscape of 2021, and what we can plan to look forward to in the year ahead …

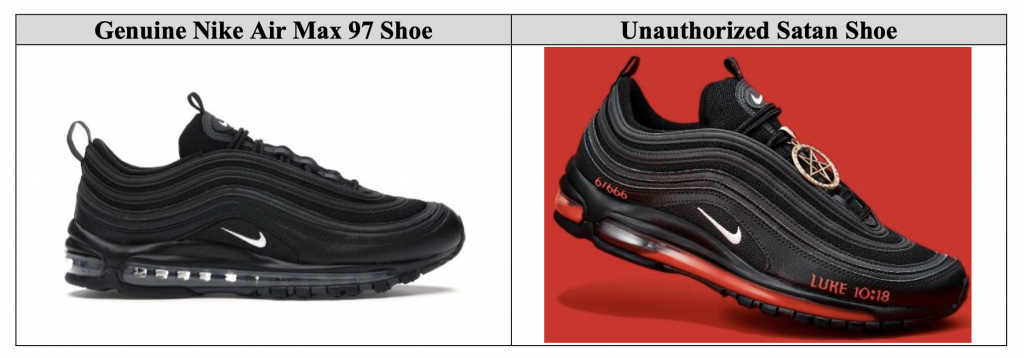

In what was easily one of the most attention-grabbing trademark cases of the year, Nike filed suit against MSCHF in March, accusing the “art collective” of running afoul of trademark law by taking 666 pairs of otherwise authentic Nike Air Max 97 sneakers and “materially alter[ing] them to prominently feature a satanic theme,” including by injecting red paint and a drop of human blood into the heels. As a result of such modifications, Nike argued that the customized sneakers were no longer “genuine Nike products,” despite bearing Nike branding.

The case settled in a matter of two weeks, but still managed to raise a number of timely issues, such as ones that center on the legality of marketing and selling trademark-bearing goods that have been modified, which has been a theme in a number of recent cases, as “bootleg” products and customized goods continue to find favor among consumers, much to the displeasure of the targeted brands.

Fast forward to September and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit took on an unrelated modification case that Swatch subsidiary Hamilton Watch filed against Vortic LLC, a company that converts antique pocket watches into wrist watches. On the heels of a district court siding with Vortic, the Second Circuit agreed that the company did not run afoul of trademark law by selling restored and modified watches consisting of a combo of original Hamilton Watch parts and Vortic parts, as well as the original Hamilton watch branding. The crux? Vortic’s use of the Hamilton marks is not likely to confuse consumers.

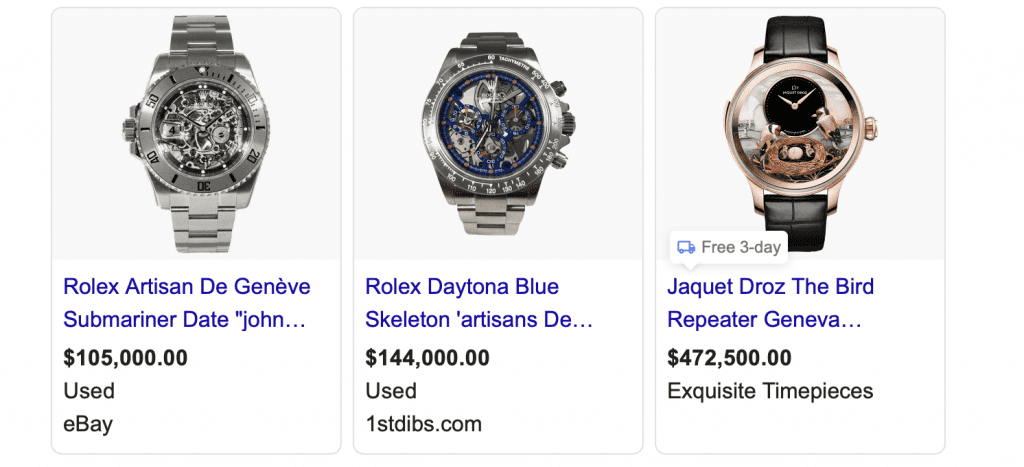

And as I have mentioned before (and stand by going into 2022) … brands should be paying attention to the burgeoning customization market, but not just from an enforcement perspective. This is fertile ground for brands, as indicated by the craze created by MSCHF’s “Satan” sneakers, and the demand for more upmarket customizations coming from Swiss watch workshop Artisans de Genève, as well as London-based watch customizer Titan Black, and Privé Porter founder Michelle Berk, which have been successfully trying their hands at respectively making already ultra-valuable watches and Hermès Birkin bags even more exclusive (and even more expensive).

A few of Artisans de Genève creations at resale

Forward-thinking luxury brands – like Gucci – will likely start inching further into this space in an effort to connect with their most loyal and deep-pocketed consumers, who are looking for hard-to-get goods to supplement their collections of their accessories of choice, and to stand out in a market where luxury goods are more readily available than ever thanks to the rise of the secondary market.

The future of retail is unabashedly omnichannel, and this is prompting retailers to reevaluate their established ways of doing business, taking into account the role of physical outposts and the need to prioritize e-commerce and mobile commerce. This means that at least a few big-name department stores, in particular, are navigating (or better yet, being pushed by investors to navigate) the swiftly-changing retail landscape – and looking to maximize the benefits of their historically brick-and-mortar-dependent model – by putting a formal divide between online and physical stores. Enter: the e-commerce spin-off.

Saks has, of course, been the posterchild of this move, but other names – from Neiman Marcus to Nordstrom – have been cited as potentially attractive targets for such a reorganization, and this trend will likely continue into 2022, as companies look to bolster their values for shareholders. You can read more about this here.

Consumer interest in sustainability and broader ESG issues has pushed many brands to bolster their bottom lines by making oversized marketing efforts and/or more-ambitious-than-objective “eco-friendly” statements. To date, brands have largely managed to appease consumers and investors with proclamations about their “eco” efforts, and skirt legal ramifications for questionable claims due to the traditional lack of regulation in the ESG realm.

The status quo appears to be changing, though, potentially even in instances when the marketing is vague and aspirational in nature. One need not look further than the messages being sent by the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) – and the frequency of those messages – to see that developments are afoot. The SEC posted five public statements and two press releases on its website between February 24 and April 12, alone, all of which focused primarily on ESG. Among them: an announcement about the creation of a Climate and ESG Task Force in order to “develop initiatives to proactively identify ESG-related misconduct,” and another about a potential plan to adopt “mandatory, rather than voluntary, standards” for reporting ESG disclosures.

At the same time, consumers are taking issue with the veracity of companies’ claims, with Allbirds and Canada Goose both landing on the receiving end of lawsuits that aim to hold them accountable for sustainability centric advertising claims. Regulators and watchdogs are paying attention, too, as indicated by an investigation into an adidas ad in France, and the recent probe by the NAD into Everlane’s marketing.

Still yet, in a different kind of lawsuit, David Yurman made mention of ESG marketing in the trademark infringement case that it recently filed against Mejuri, asserting that “Mejuri’s business practices contradict its claim to customers,” namely, its marketing of itself a “socially-responsible” company, and its claims that “[s]ince day one, it’s been our mission to engage with the jewelry industry in a way that compliments [sic] our values and those of our customers.”

It will be interesting to see if more companies begin taking issue with defendants’ ESG claims in connection with infringement cases, if for no other reason than to shed a negative light on competitors from a PR perspective.

The rise in online consumption has taken on increased importance for brands from a distribution point of view, leading to lawsuits over sales taking place on sweeping marketplace sites. A decision centering on unauthorized sales of cell phone and tablet cases online, including on Amazon’s marketplace, in a pending trademark and false advertising case is one of the most striking of the year, and one that is likely to have an impact on fashion’s longstanding fight against gray market goods.

In an order and opinion dated November 10, Judge Regina Rodriguez of the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado sided with Otter Products, granting the Colorado-based electronics accessory company’s motion for partial summary judgment in the case that it filed against Triplenet over its unauthorized sale of OtterBox products. The case got its start in February 2019 when Otter Products filed suit against Triplenet and affiliated entities, accusing the companies of trademark infringement, unfair competition, false advertising, and deceptive trade practices in violation of the Colorado Consumer Protection Act.

According to Otter’s complaint, the defendants were offering up products bearing its trademarks on various e-commerce sites, including Amazon’s third-party marketplace site, and advertising them as “100% authentic” and as coming with an “OtterBox limited lifetime warranty,” despite falling outside of the company’s carefully-controlled network of authorized sellers. The problem, according to Otter, is that the “products sold by Triplenet are materially different from genuine Otter products because they do not come with the Otter warranty,” as the company’s warranty only extends to products sold by authorized sellers.

Addressing Triplenet’s argument that it should be shielded from Otter’s trademark infringement and unfair competition claims by the first sale doctrine (i.e., the trademark tenet that provides that the resale of genuine trademarked products generally does not constitute trademark infringement), Judge Rodriguez pointed to the two exceptions to the doctrine – the “material difference” and “quality control” exceptions – and held that both are apply in the case at hand.

Not limited to sales on Amazon, Chanel also seemed to take issue with the sale of its products online in a trademark lawsuit this year, in which it argued that reseller Crepslocker’s offering of its products and use of Chanel trademarks diverges from the conditions traditionally associated with the sale of Chanel goods, and thereby, infringes Chanel’s famous trademarks. The luxury stalwart was put off, in part, by Crepslocker offerings of its goods online, arguing that it “has never made nor permitted any online sales” of its “fashion products,” and instead, “such products can only be purchased in person, in a very small number of carefully chosen and controlled luxury retail environments.”

The Chanel case has since settled, but the district court’s decision in the OtterBox case very well might serve as ammunition – and a blueprint – for brands looking to take similar action in 2022.