An interesting little trademark scenario popped up this week (in addition to those awfully-ugly red-soled Trump sneakers). Jacquemus teased part of its latest collaborative collection with Nike on Instagram. In particular, the French fashion brand showcased a handbag design, that of the Le sac Swoosh, which takes the form of Nike’s famed Swoosh – albeit with a zipper and adjustable shoulder strap, and a little golden-hued name plate that says Jacquemus.

Social media users were quick to note that the long nails and tattoos depicted in one of the images belong to Nike-sponsored American sprinter Sha’Carri Richardson, who will presumably serve as the face of the campaign for Jacquemus’ latest collection. However, what caught my eye was the shape of the bag, which is, of course, meant to evoke one of Nike’s most famous trademarks: the Swoosh that it has been using since the early 1970s.

What makes the Le sac Swoosh particularly notable (I think) is that the Swoosh-shaped bag is something of a reversal of what we are accustomed to seeing when it comes to trademarks rights and handbags. Traditionally, handbags garner trademark (or more specifically, trade dress) rights not by taking on the form of the underlying company’s most famous logo – and that probably is for obvious (and practically-driven) reasons. Instead, rights are usually amassed the other way around: Companies consistently sell “it” or other staple bags for long enough, market them with enough robustness, generate a sizable volume of revenue from sales of the bags, engage in enduring product placements and enjoy unsolicited third-party media attention, etc. – and voila, they very well may have a protected handbag configuration on their hands.

The Birkin bag – which I previously broke down from a secondary meaning perspective here – is the most obvious example here. The crux: As a result of its “widespread and constant use” of the “distinctive shape” of the Birkin bag (think: the rectangular sides and bottom, dimpled triangular profile, rectangular flap with three protruding lobes, keyhole-shaped openings, etc.) since 1984 and the “notoriety of the BIRKIN handbag,” the configuration of the bag has come to be act as a source identifier for Hermès. That is part of what Hermès successfully argued in furtherance of its Birkin-centric trademark case against MetaBirkins creator Mason Rothschild. (More about that still-ongoing case can be found right here.)

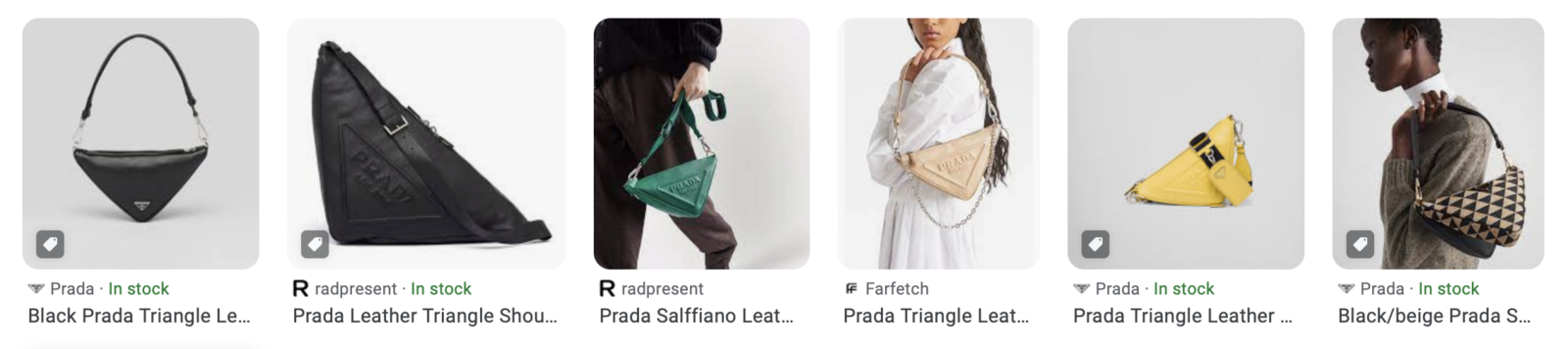

Interestingly, Nike and Jacquemus are not the only ones engaging in this flip-flopped branding-heavy exercise. Prada comes to mind, as well, thanks to its relatively recent lineup of triangle-shaped shoulder bags, which appear to be one of its latest efforts to extend the reach of its triangular trademark beyond the usual metal adornments on its handbags.

More broadly, I think these are examples of companies looking for ways to incorporate branding beyond the most obvious and traditional (and connect with consumers in a particularly maxed-out market filled with branding). And thus, these instances fall in line with other efforts by brands, such as Valentino and its enduring use of color (a specific shade of fuchsia to be exact) to consider how they are using indicators of their brand and potentially think outside of the box a bit. More to come on this, I am sure.