At the start of the pandemic, consumers were bombarded with a new and hastily constructed form of advertising. In those “uncertain times,” customers were promised, they could rely on their favorite brands for help. The ads – often featuring somber piano music and/or declarations that everyone was “in this together” – were ubiquitous. Now that the dust has settled on the COVID-centric advertising flurry, new research reveals the tactics behind these often-largescale advertising campaigns, and why consumers (and thus, brands, themselves) should be wary of marketing in a crisis.

When COVID first began to plague individuals across the globe, and governments were unsure about how to respond, corporate advertising sought to define the pandemic in ways that made companies – and their products – an essential part of whatever the solution might turn out to be. In a review of advertising campaigns that ran between mid-March to the end of April 2020, companies used ads to tell three main types of stories about COVID. Some, like the global shipping giant Maersk, emphasized the supply chain impact of the pandemic and pointed to their role helping to get essential equipment to the right places. This kind of marketing defined COVID as a crisis of logistics – a problem for which corporate managers could argue they have the most specialist expertise.

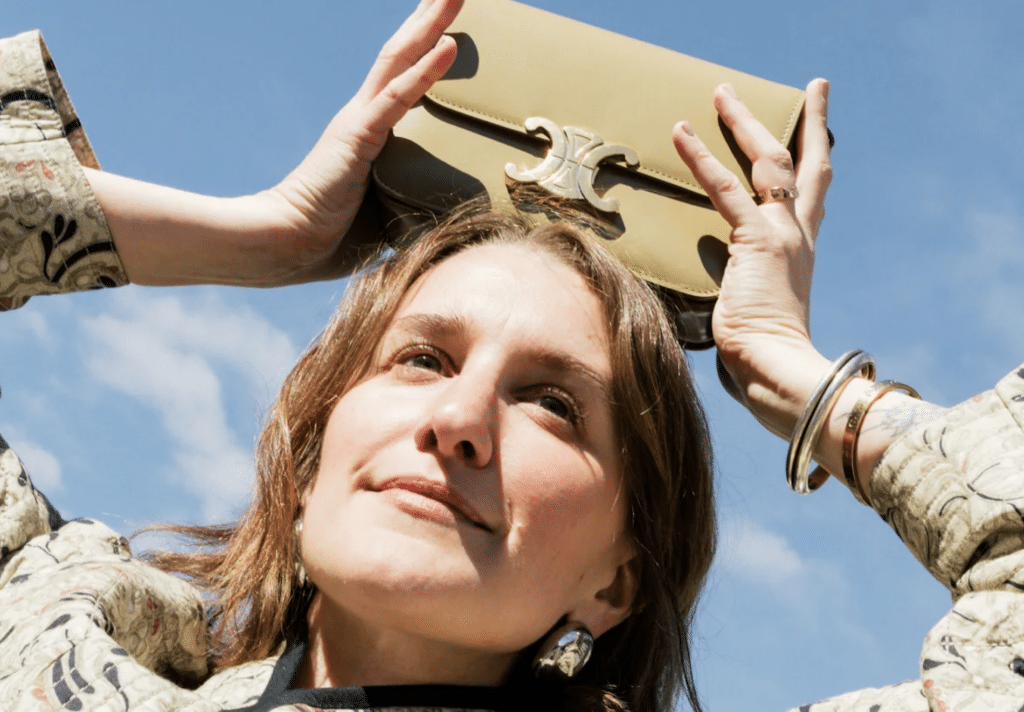

Others, especially consumer goods brands like Starbucks, concentrated on the financial side of the situation, and their role in donating food or money to those in sudden need. This kind of marketing defined COVID as a crisis of capital. If the problem is not enough cash, then wealthy corporations can swoop in as heroes by freeing some up quickly. And then there were those – especially fashion and luxury brands – that focused on the emotional impact of the pandemic, and pointed to their products as a way to make the experience easier and more enjoyable. These adverts made the case that personal consumption – shopping from your lockdown – could be a form of humanitarian heroism, with you as the grateful recipient, or a way of taking care of yourself.

But there were risks attached to these messages, and not all of them landed well. Some ads seemed oblivious to the wider social problems that were making the crisis harder for some to bear. Fashion advertisements targeted at women that described the pandemic as a kind of “staycation,” for example, sat uncomfortably next to news reports about women who were leaving the workforce under the crushing burden of childcare and housework. E-cigarette advertisements encouraging consumers to take up vaping “for your health” invited a backlash when hospitals were filled with COVID patients on ventilators.

Some companies even provoked consumers by mocking the severity of the pandemic, including an Italian ski resort that invited travelers to “experience the mountain with full lungs” in a place “where feeling great is contagious.” All the while, social media companies struggled to stamp out misinformation from “influencers” hired by wellness brands to promote untested products as COVID-19 cures.

Even companies behind advertising campaigns that took the pandemic seriously found themselves on shaky ground. When the UK was coming out of its first lockdown, cleaning brand Dettol went viral (in the wrong way) when it appeared to be encouraging commuters to return to the office. Some consumers conflated the ads with government public service announcements promoting shopping as a way of boosting the economy. The misconception contained a grain of truth, as Dettol was the government’s corporate partner for sanitizing public transport. Indeed, several brands in our research mentioned partnerships with government as one of the benefits of the crisis.

Meanwhile, advertisements encouraging consumers to shop to “help” rebuild the economy (and companies in it) have proliferated.

Beyond the Pandemic: Consuming with a Conscience?

Advertising that addresses social concerns is common, and not just in relation to COVID. In fact, such advertising extends to a range of causes where consumers are primed to see corporate solutions for everything from poverty to climate change. Our research shows that this type of advertising is frequently designed to influence how the public understands social problems, and encourages people to think of ethical consumption as a way of helping.

As others have argued, such marketing related to good causes “creates the appearance of giving back, disguising the fact that it is already based in taking away.” For example, consumers can be deterred from campaigning for more radical change, believing they have already played their part through “ethical” purchasing. One familiar example is when companies boast that a percentage of proceeds from certain products goes to a social cause. The amount donated is often small while the revenue the new product generates for the company is considerable. (Another comes in the form of fashion industry capsule collections that tout the products as “sustainable” or “recycled,” and thus, may deter consumers from cutting back on their consumption due to the “eco-friendly” nature of the offerings.)

Against this background, the risks of attaching a social issue to an advertising campaign are considerable – for the company, the consumer, and the cause, itself. Our research suggests that not every time is the right time for advertising, and we should beware of brands bearing gifts.

Lisa Ann Richey is a Professor of Globalization at Copenhagen Business School. Maha Rafi Atal is a Lecturer in Global Economy at the School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Glasgow. (This article was initially published by The Conversation.)