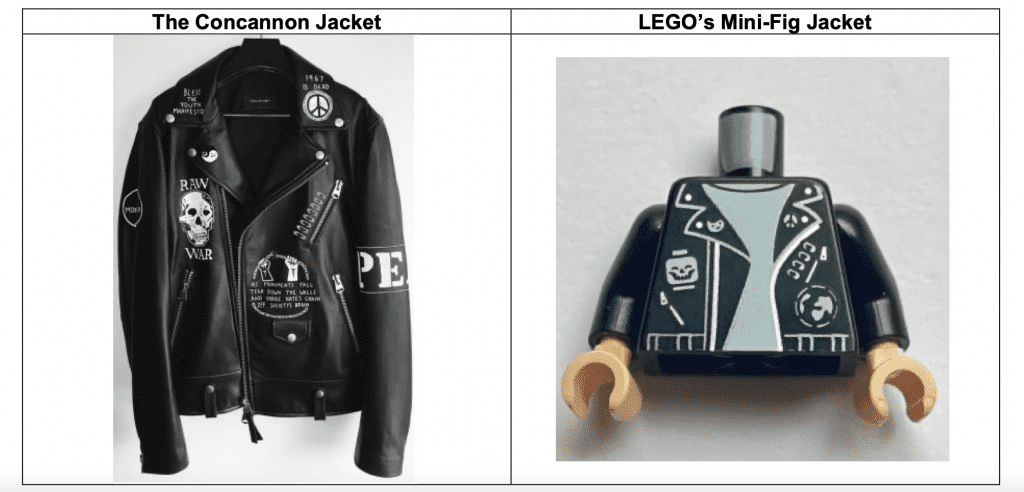

An artist accusing LEGO of copyright infringement for allegedly replicating a custom leather jacket that he created – albeit without his authorization and without compensating him – has bulked up his lawsuit against the Danish toy titan. As first set out in an amended complaint that he filed with a Connecticut federal court in February and then in two amended complaints since then, plaintiff James Concannon asserts in the lawsuit that LEGO is not merely on the hook for copyright infringement for adorning the LEGO version of Queer Eye cast member Antoni Porowski in its Queer Eye-themed set in a “copycat” jacket, but is also liable for trade dress infringement for ripping off the jacket design.

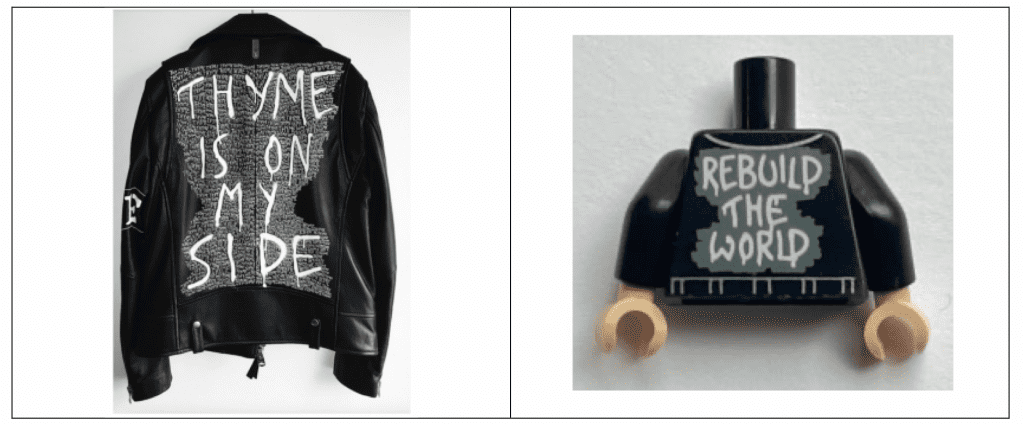

In three amended complaints, the most recent of which was lodged with the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut on June 13, Concannon asserts that “over the past decade, [he] has achieved notoriety as the creator of a popular line of t-shirts, jackets, and accessories, which are instantly recognizable … because they feature short, provocative statements in hand-painted, graffiti-style lettering.” The “unique combination of provocative, tongue-in-cheek phrases relating to pop culture, with hand-painted, graffiti-style lettering” – which is what Concannon is claiming (unregistered) trade dress rights in – is “not only a hallmark of [his] aesthetic,” he claims, but it also serves as an indicator of source. (Note: Concannon is claiming common law rights since he lacks a registration for the alleged trade dress here, which likely would not be registered by the USPTO because, among other things, it is a phantom mark.)

Given that the “look, feel, and aesthetic” of the products that display the trade dress is consistent, Concannon argues that the trade dress is “immediately recognizable and distinctive.” Moreover, Concannon claims that his wares have been the subject of “significant media attention” thanks to their appearance in film and television shows and their promotion by celebrities, such as “Lady Gaga, Lil Wayne, Suki Waterhouse, Jaime King, and punk rock icons like Jimmy Webb and the band Death,” which has resulted in “consumers associat[ing] this unique and distinctive combination of elements with [his] products.” And, of course, Porowski has promoted Concannons designs, wearing a number of his garments on episodes of Queer Eye, including the jacket that LEGO allegedly copied.

Further underscoring the alleged “distinctiveness” and value of his trade dress, Concannon asserts that “numerous infringers have sought to capitalize on the strength of [his] brand by selling counterfeit versions of [his] products.”

With this in mind, Concannon claims that the design of his products have acquired distinctiveness and secondary meaning in the marketplace, enabling the combination of elements to function as an indicator of source. (But wait a minute … Do Concannon’s “short, provocative statements in hand-painted, graffiti-style lettering” really serve as indicators of source? Or do they primarily serve as – and are viewed by consumers as – decorative features of the products upon which they appear?)

To the extent that LEGO altered the original text on the back of the jacket, Concannon says that the toy-maker did so “in a way that is still intended to evoke [his] signature style and brand so that the infringing product would look like a Concannon product and benefit from the association with Concannon’s trademark.” As a result, Concannon alleges that LEGO “creates a false sense of affiliation or sponsorship” with him in an attempt to confuse consumers.

In addition to claiming trade dress rights in the design that appears on the jacket and infringement in connection with LEGO’s use of a similar design for its Porowski figurine, Concannon sets out copyright infringement claims, as well. Specifically, Concannon argues that LEGO “painstakingly copied not only the individual creative elements of the jacket, but the unique placement, coordination, and arrangement of the individual artistic elements, as well,” for which he maintains a U.S. copyright registration. By “copying, publicly displaying, distributing, and creating derivative works of the infringing product, which is substantially similar to, derive from and a derivative of [his] original artwork and design, without [his] authorization or other permission,” Concannon claims that LEGO is on the hook for copyright infringement.

Unless stopped by the court, Concannon asserts that LEGO “will continue to realize unjust profits, gains, and advantages as a proximate result of its infringement.” As such, he states that he is entitled to an injunction, and is also seeking damages “for all damages [he] suffered and for any profits or gain by [LEGO] attributable to infringement of [his] copyrights and/or Trade Dress in amounts to be determined at trial.”

“While Concannon’s case focuses on fashion in one of its most miniscule forms, it may have larger repercussions,” Finnegan’s Mary Kate Brennan and Margaret Esquenet stated earlier this year, noting that from a copyright perspective, the court is likely apply the principles set forth in Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., which establishes that copyright protection only extends to pictorial, graphical, or sculptural elements that are separable from a useful article. Given that Concannon’s leather jacket, itself, is a “useful article,” his copyright claim centers on the artwork on the jacket, and whether it is protectable and if so, whether LEGO’s version is “substantially similar.”

As such, lawyer and intellectual property researcher Mike Dunford says that from a copyright perspective, the lawsuit against LEGO really hinges on whether or not the court finds that the “unique placement, coordination, and arrangement” of the elements that appear on the jacket are, in fact, “protectable and infringed notwithstanding the substitution of different individual artistic elements.” Dudford contends that “at least some of the elements of the two-dimensional artwork are not independently protectable,” and says that he is not sure if some of them are even protectable in terms of “their position on a jacket with other elements – in particular, the peace sign on the lapel.”

As for the trade dress infringement claim, which is judged by likelihood of consumer confusion (as distinct from the copyright infringement test of substantial similarity), this is likely to be even more of an uphill battle. It is not difficult to imagine LEGO (successfully) killing Concannon’s claim by arguing that the style of artwork that appears on his clothing is purely decorative and does not serve as an indicator of source.

The case is Concannon v. Lego Systems Inc., 3:21-cv-01678 (D. Conn).