The influencer economy is thriving, nabbing a valuation of approximately $250 billion last year, per Goldman Sachs, and expected to reach to nearly $500 billion by 2027. Behind this swiftly-growing segment, one that thrives on curated aesthetics, distinctive voices, and carefully-crafted brand identities that command follower engagement and give rise to lucrative sponsorship deals, a striking lawsuit pits one heavily-followed influencer against another and questions whether one’s personal “aesthetic” or “vibe” can be protected by the law.

A Case Over Copycat Aesthetics

The closely-watched lawsuit got its start in April 2024 when influencer Sydney Nicole Gifford filed suit against Alyssa Sheil in federal court in Texas, alleging that her fellow influencer is engaging in widespread copyright infringement, trade dress misappropriation, and unfair competition. Specifically, Gifford – a Texas-based influencer with over half a million followers across Instagram, TikTok, and Amazon Storefront – asserts that Sheil systematically copied her content, aesthetic, and even personal branding elements to mislead followers and gain an unfair competitive advantage in the influencer market.

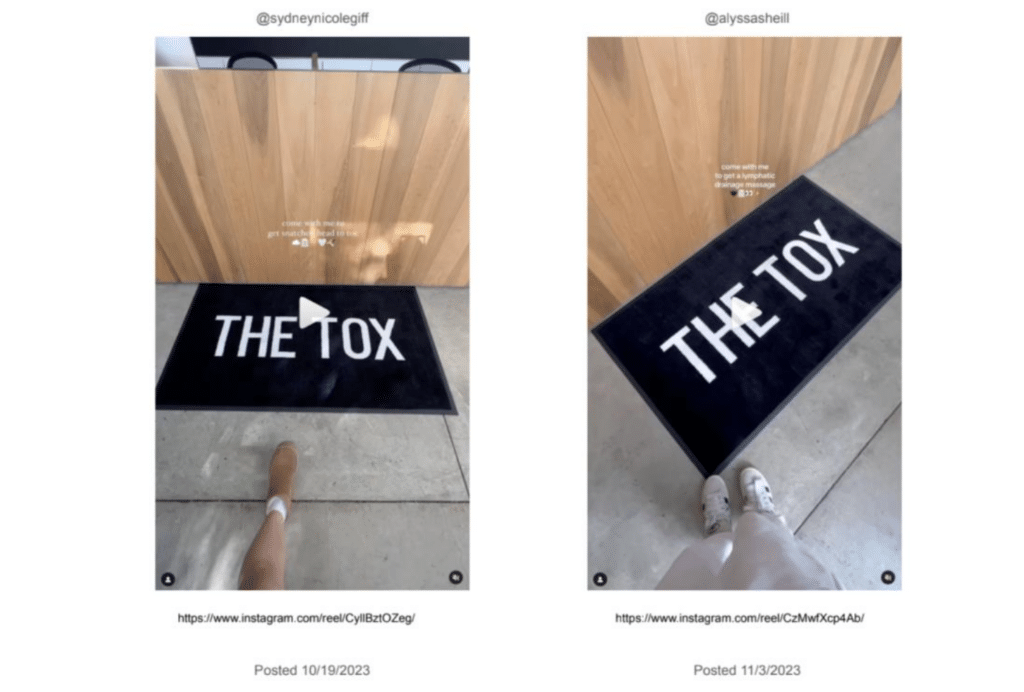

In her complaint, Gifford claims that Sheil – a lesser-known influencer – directly reproduced her copyrighted images, appropriated her trade dress, and even mimicked her personal appearance, including her hairstyle, outfits, poses, and a nearly identical flower tattoo.

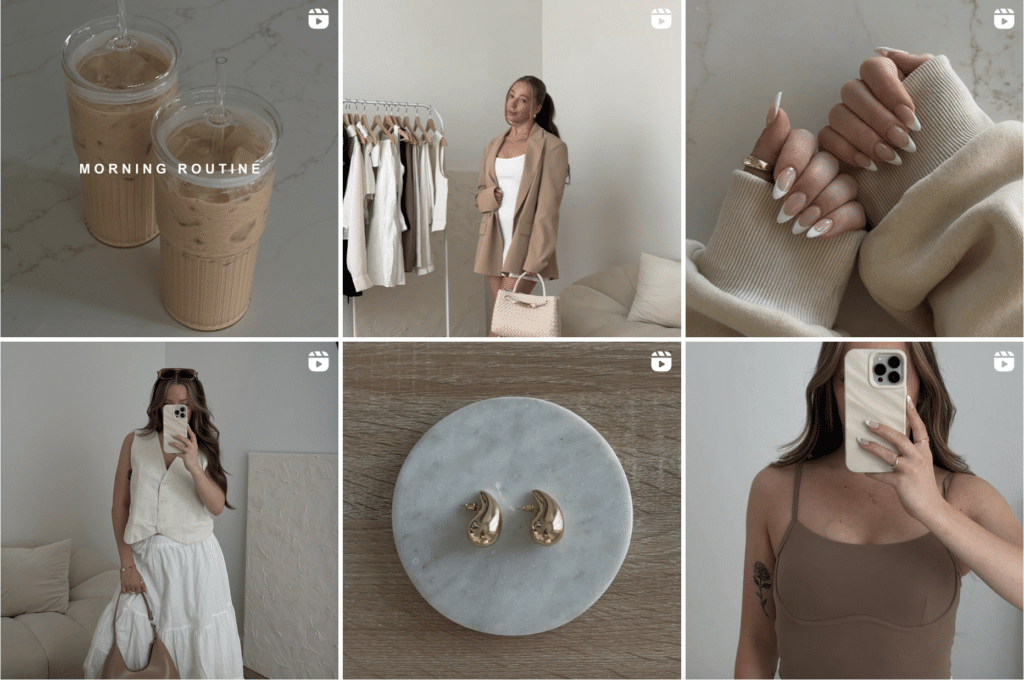

> What does the trade dress at issue consist of? Gifford alleges that “markers of [her] distinct trade dress include: [her] promotion of products only falling within the monochrome cream, grey, and neutral-beige color scheme; styling of products in modern, minimal backdrops; creation of content featuring herself; and [her] distinct relatable way of speaking to followers.” She further asserts that she maintains rights in her use of “monochrome cream, grey, and neutral-beige colors coupled with modern, minimal, sophisticated styling of Amazon products via [social media] platforms.”

With the foregoing in mind, Gifford alleges that Sheil’s use of a similar trade dress will lead to customer confusion. In particular, she asserts that Shiel’s “mimicry of [her] appearance and the overall image associated with [her] brand, such as the content on and the appearance of [her social media profiles], the parties’ respective bio.site websites, and the parties’ respective apparel lines, causes the two to be so similar that followers will be and are unable to differentiate between the two.”

The potential for consumer confusion is “further exacerbated by the algorithm employed by social media platforms, such as TikTok, which recognizes colors, shapes, and stylings, among other factors, to suggest videos users may be interested in,” Gifford claims, arguing that “users may watch one of [her] videos and immediately be recommended one of [Shiel’s] videos because of the stark similarities in trade dress and feature of identical products.” In such a scenario, Gifford argues that “a user is likely to confuse the two videos as coming from the same source.”

TLDR: In furtherance of her lawsuit, Gifford complaint essentially seeks to hold fellow influencer Sheil liable for copying the “vibe” of her social media posts and curated lists that promote Amazon products.

An Early Answer from the Court

The court provided some early insight into the merits of the influencer-centric lawsuit when it adopted a magistrate judge’s Report and Recommendation in response to Sheil’s motion to dismiss, in which are argued (among other things) that Gifford failed to sufficiently allege that she appropriated Gifford’s “likeness” and that Gifford cannot be identified from her posts. In a filing in November, Magistrate Judge Dustin Howellrecommended dismissing Gifford’s tortious interference, unfair competition, and unjust enrichment claims, while allowing her core copyright infringement, trade dress infringement, DMCA violations, and misappropriation of likeness claims to proceed.

At a high level, the magistrate judge presented the following findings/recommendations, which were adopted by Judge Robert Pitman last month …

> Copyright Infringement & DMCA Claims: The court found that Gifford adequately pleaded that Sheil made use of her copyright-protected content – alleging that Sheil willfully and intentionally replicated Gifford’s aesthetic and product recommendations. The court also upheld Gifford’s DMCA claim, ruling that Sheil’s actions, such as removing Gifford’s name from original content and posting near-identical recreations, could violate federal law.

> Trade Dress Infringement Claim: The judge found Gifford’s trade dress claim plausible, given that her neutral, beige aesthetic, coupled with minimalist styling and content curation, may be legally protected. The ruling acknowledged that Sheil’s alleged copying of color palettes, product styling, and branding identity could cause consumer confusion.

> Misappropriation of Likeness: A particularly striking aspect of Gifford’s complaint alleges that Sheil not only copied her content but actively imitated her physical appearance, poses, and even her voice. The court ruled that these allegations were sufficient to move forward, emphasizing that intentional impersonation in a way that misleads followers could constitute misappropriation.

> Tortious Interference, Unfair Competition & Unjust Enrichment: The court found that Gifford did not sufficiently plead that Sheil had actively interfered with her Amazon contract or caused a breach, leading to the dismissal of her tortious interference claim. The court also found that her unfair competition and unjust enrichment claims – which alleged that Sheil profited unfairly from copying Gifford’s content – are preempted by federal copyright law. The court noted that such claims cannot stand independently if they are primarily based on copyright violations.

An Amended Complaint

On the heels of the court dismissing some of her causes of action, Gifford lodged an amended complaint late last month, arguing that Sheil’s alleged copying is not limited to a handful of posts but rather constitutes a deliberate “pattern” to mirror Gifford’s entire brand identity.

Detailing the extent of Sheil’s alleged copying, Gifford points to the following: More than 30 Instagram and TikTok posts from Shiel that allegedly copy her content; recreations of her styling, camera angles, and captions by Shiel; direct duplication of her Amazon product recommendations and curated “Idea Lists” on Amazon Storefront; a nearly identical “bio.site” landing page, including background colors, fonts, and links; a similar apparel line launched by Sheil under “Retail Therapy Club,” allegedly mirroring Gifford’s “Wardrobe Essentials Club;” and Sheil’s tattoo, which is “nearly identical” to a flower tattoo that she has.

Each of these “element[s] is a distinctive characteristic associated with [Gifford]” that consumers have come to recognize as her own, Gifford maintains.

A Landmark Case?

The lawsuit is one of the first legal battles to test the limits of copyright and trade dress protection in the influencer industry. As the magistrate judge noted, “This case appears to be the first of its kind – one in which a social media influencer accuses another influencer of copyright infringement based on the similarities between their posts that promote the same products.” If Gifford succeeds on her remaining claims, the case could establish important legal precedent for influencers seeking to protect their content, aesthetic, and elements of their personal branding.

This case highlights a growing legal issue in social media marketing: as influencers cultivate distinct brand aesthetics, how far can competitors go in borrowing elements without running afoul of the law? The line between inspiration and infringement remains murky here, particularly when trends and platform algorithms reward similar visual styles. For Gifford, however, the case is clear: she alleges Sheil’s actions resulted in monetary loss, decreased engagement, and dilution her credibility. As such, she is seeking monetary damages and injunctive relief to prevent further copying by Shiel.

The case is Gifford v. Sheil, 1:24-cv-00423 (W.D. Tex.).