Endless media coverage of the future potential of cryptocurrencies – from Bitcoin and Ether to currencies like Dogecoin – has made digital money a hot topic. In the simplest terms, digital money can be defined as a form of currency that uses computer networks to make payments. One of the main differences between digital money and physical currency, such as cash, is that digital money lacks any identifying features that make it unique. If you take a glance at any bank notes you might have, you will quickly notice that each note has a serial number — a unique string of letters and numbers that marks the uniqueness of that bill.

But as we know, digital objects, such as songs or images, are easily reproducible infinitely on the internet. What prevents us from reproducing the digital money in our bank accounts so easily? The reality is, most of us have been using digital money all along. It is not the digital nature of crypto that differentiates it from digital money, but rather how it ensures the ownership of digital property that marks it as transformational. The problems of digital money and who owns it are likely to increase in complexity, with far-reaching implications in everyday life. The Counter Currency Laboratory, a new initiative based in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Victoria, was established to explore these questions, including by documenting the present and future of money, and its effects on how we live.

Crypto v. Credit Cards

Commercial banks and payment networks, such as those that use credit cards, safeguard the uniqueness of our digital dollars. These institutions guarantee that we do not go around spending the same digital dollar more than once. Once we spend digital money, banks deduct it from our accounts so that it cannot be spent again.

Not a novel phenomenon, the first widely used form of digital money was credit cards with magnetic stripes, and the use of a magnetic stripe encoded with identifying information was first introduced almost 50 years ago. This form of digital money went into widespread use in the 1970s and 1980s, spurred by the invention of electronic point of sale terminals connected to computer networks managed by the likes of Visa and Mastercard.

But how does this digital money work exactly? When paying for something in a store, the buyer taps their credit card on the digital terminal, and the merchant’s bank forwards the details of the credit card to the network. This credit card network requests authorization of the payment from the cardholder’s bank. The cardholder’s bank validates the cardholder’s details and the amount of available credit and then approves the purchase.

Hundreds of millions of these digital money transactions occur every day. Although such a transaction involves a buyer, a seller, two banks, and a credit card network, no physical money is actually exchanged. Rather, a series of messages are transmitted resulting in a debt incurred by the shopper to their bank and a credit in the merchant’s bank account. In this sense, the digital money used here is not a material medium of exchange, such as bills or coins, but rather a unit of account entry. This digital money is a credit or debt in the digital ledgers maintained by the banks of both the merchant and the consumer. Other forms of digital money – such as debit card transactions or e-transfers – work similarly.

No Central Authority

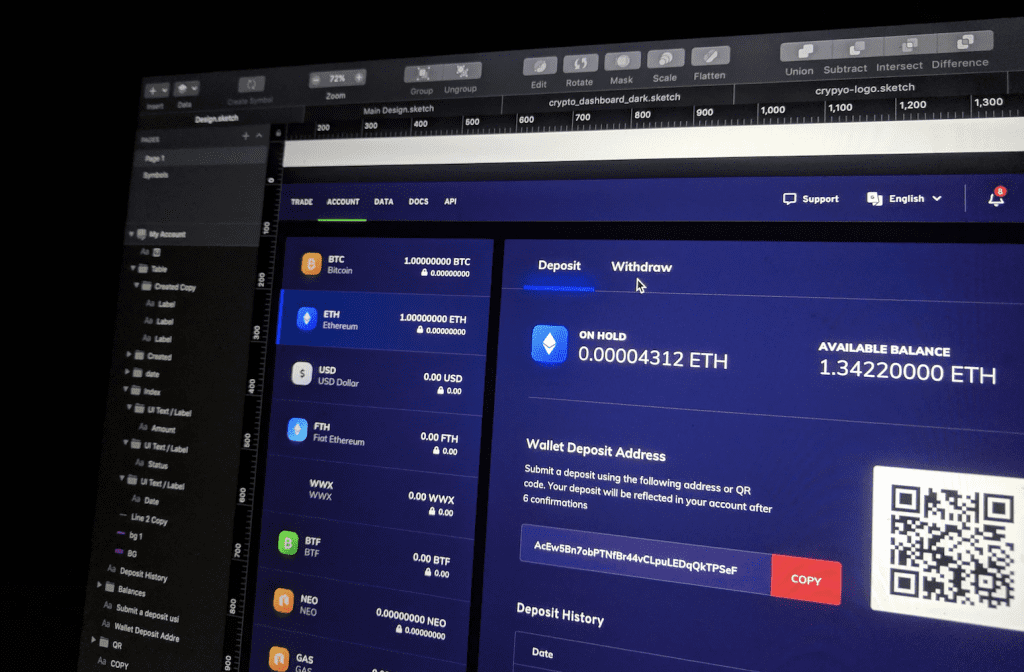

Cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, differ from the forms of digital money that are already commonly used by consumers around the world. The main difference is that when payments are made, a blockchain replaces the relationship between the two banks. (A blockchain is a list of records containing transaction data that is held in a distributed ledger, which is a digital record of the account books for crypto transactions. Ledger copies are stored and maintained by the thousands of computers that participate in the cryptocurrency network.)

While digital money poses the problem of double spending (How can one ensure that the same money in an individual’s account is spent more than once?), blockchain technology solves this problem without recourse to a central authority.

In commonly used forms of digital money, the computer servers that facilitate the credit card network prevent double spending; these servers ensure that a cardholder cannot use the exact same digital dollars used for buying groceries in the supermarket to also buy a round of drinks at the pub. In the Bitcoin network, for example, any attempt to spend the same Bitcoin twice would be invalidated collectively by all the computers in the network, which would prevent any attempt to spend the same digital money in two places.

Crypto and Digital Property

With the foregoing in mind, the actual revolutionary development brought about by crypto is not necessarily the digital nature, but rather, its ability to enable the transfer of ownership of digital assets without recourse to a centralized authority. The infinite replicability enabled by the internet has challenged notions of property that have long undergirded modern civilization. In theory, the same elements of blockchain and distributed ledgers that enable the transfer of ownership of digital currencies may be able to bring order to intellectual property on the internet. Indeed, it is these aspects of crypto that may have the most lasting impact on how we live in cyberspace and the “real” world.

Daromir Rudnyckyj is a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Victoria. (This article was initially published by The Conversation.)