Checkerboard prints are everywhere – again, Wall Street Journal fashion editor Jacob Gallagher wrote recently, noting that regardless of “whether they remind you of surrealism, ’70s ska bands or [Fast Times at Ridgemont High character] Jeff Spicoli’s Vans, graphic grid prints are back,” with luxury titan Louis Vuitton and budding young brands, alike, “pushing the pattern” in a nod to the enduring appeal of the eye-catching print. Look beyond the onslaught of checkered wares – from Vans sneakers and Clare V. bucket hats to J.W. Anderson vests and Louis Vuitton bags – that have found a home on the runway and on brands’ e-commerce sites, and you will see that these prints are currently at the center of a number of noteworthy legal battles, in which brands are claiming rights in certain versions of the ubiquitous pattern for use in connection with certain goods/services.

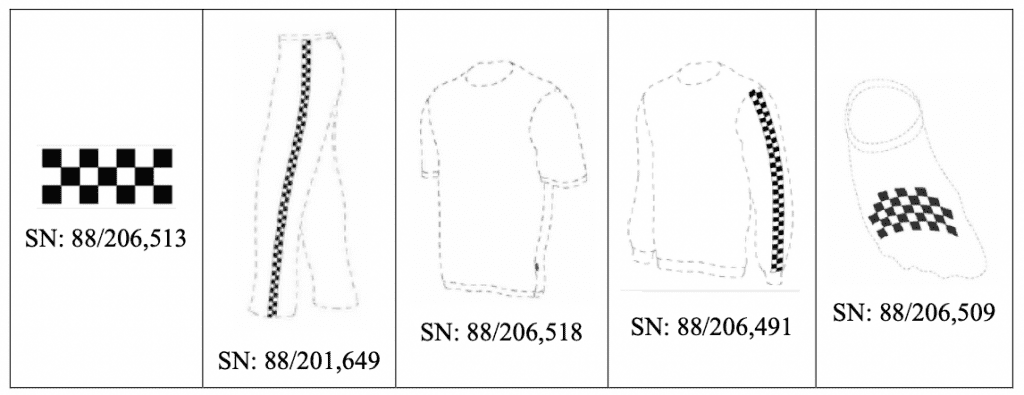

One such battle has pitted Nike against Vans in light of the latter’s attempt to register various iterations of the checkerboard print – which it famously started displaying on slip-on sneakers back in the 1970s with – the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”). The two parties’ spat dates back to at least 2019 when Nike initiated an opposition proceeding to block the registration of a Vans trademark that consists of a “non-repeating checkerboard pattern consisting of three rows arranged in a rectangular form, with the top and bottom rows consisting of four shaded and three non-shaded squares, and the middle row consisting of three shaded and four non-shaded squares” for use on apparel.

Nike argued in the December 2019 notice of opposition that it filed with the USPTO’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (“TTAB”) that registration of Vans’ checkerboard pattern would not only be inappropriate because the mark is “a design element that is merely decorative or ornamental when used in connection with apparel” that consumers “do not perceive … as having any source-identifying significance, but a registration “would damage and injure [Nike] by impeding [its] (and the public’s) ability to use common design elements that it has long used.”

Hardly a theoretical issue, Nike argued that it has been selling apparel products that include “checkerboard patterns of various sizes, shapes, and colors placed in various locations on shirts and pants, such as the front, side, back, and inside thereof” since at least the 1980s. And it is not alone; Nike argued that no shortage of other brands have used – and continue to use – checkerboard prints on their offerings, as well.

Against that background, Nike asserted that Vans’ attempt to “broadly register checkerboard designs in connection with apparel” by way of a number of applications for registration that it has filed with the USPTO beginning in November 2018 demonstrates the skatewear brand’s “intent to impede the ability of others to use checkerboard designs in connection with apparel.”

As of this week, that opposition is still underway, and in fact, counsel for Nike is looking to have it consolidated with additional proceedings that it has initiated since. It turns out that the Beaverton, Oregon-based sportswear titan did not stop after filing the December 2019 opposition against Vans; it filed an additional opposition to block the registration of a separate Vans checkerboard mark for use on apparel and socks that spring. And in April 2020 and March 2021, respectively, after the USPTO agreed to register two of Vans’ checkerboard marks, Nike initiated cancellation proceedings, asking the TTAB to revoke the registrations.

At the heart of these separate (but largely similar) proceedings is Nike’s argument that “each variation of [Vans’] checkerboard pattern is: (1) ornamental and fails to function as mark, and/or (2) is nondistinctive and incapable of acquiring distinctiveness,” and thus, should not be registered as marks.

Battles Over Damier

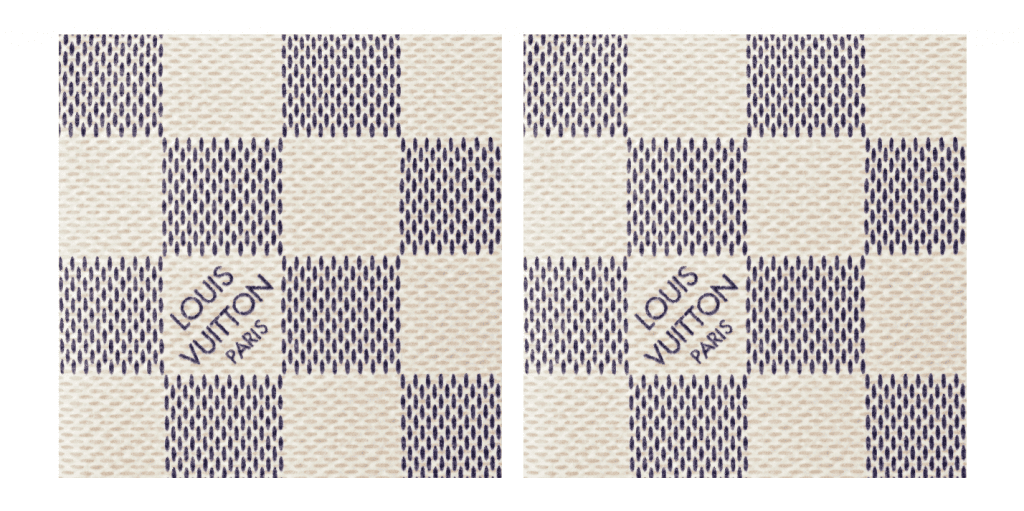

All the while, in a separate set of battles over a checkboard print, Louis Vuitton has repeatedly faced pushback over its rights in its Damier pattern, with the French fashion house most “recently suffering a setback in the latest round of a fight with Kanbe Prayer Beads Co. over the checkered print,” according to Osaka-based trademark attorney Masaki Mikami. “In order to prevent Louis Vuitton” – which has maintained trademark registration in Japan for its Damier print for use on leather goods since 2008 – “from alleging trademark infringement and secure incontestable status, Kanbe Prayer Beads asked the Japan Patent Office for an advisory opinion,” per Mikami, and the JPO subsequently asserted (in a non-binding opinion) that Louis Vuitton’s Damier is unenforceable against the Kyoto-headquartered company.

The basis for the JPO’s finding? Article 26(1)(vi) of the Japan Trademark Law, which provides “trademark rights shall not be enforceable against any sign that consumers are unable to recognize it as a source indicator of goods or services in question.”

Before that, Louis Vuitton’s Damier print was at the center of a bigger and longer-running matter that centered on its white and gray Damier Azur trademark in the European Union, which got its start back in June 2015, seven years after the mark was registered with the European Union Intellectual Property Office (“EUIPO”) in class 18, when an individual named Norbert Wisniewski sought to invalidate Louis Vuitton’s mark, arguing that the checkered print lacked the necessary distinctiveness to operate as a trademark (i.e., to identify the single source of the goods upon which it appears).

Following proceedings before the EUIPO and its Board of Appeal, both of which sided with Wisniewski, Louis Vuitton appealed, arguing that the Board of Appeal had made an “incorrect assessment … of the inherent distinctive character of the mark,” while also erring in its assessment of acquired distinctiveness. Among other things, Louis Vuitton’s legal team argued that the evidence provided by Wisniewski in support of invalidating its registration “was sparse and lacked probative value.” (Louis Vuitton, on the other hand, filed extensive evidence with the Board of Appeal to demonstrate the secondary meaning associated with its mark in each of the EU member states.)

In a June 2020 decision, the EU’s General Court sided with Louis Vuitton, in part, and against it, in part. According to 3-judge panel, Louis Vuitton’s checkerboard Damier mark is not an inherently distinctive indicator of source, as it is “a basic and commonplace pattern that did not depart significantly from the norm or customs of the sector,” and thus, is a “basic and commonplace pattern.” However, the court also asserted that the Board of Appeal only examined a small part of the evidence that Louis Vuitton provided to show that its mark has acquired distinctiveness in the EU (meaning that consumers have come to link the pattern with a single source), thereby, opening the door for a finding in its favor.

A few key takeaways from the General Court’s decision on building and showing secondary meaning include: (1) the burden to prove acquired distinctiveness through use is on the trademark holder; (2) the use made of the mark must have originated from a particular undertaking; (3) a variety of factors determining use of the mark must be taken into account (i.e., market share; breadth and geography of use, marketing spend, etc.); (4) distinctive character may be achieved by use of the mark in conjunction with another registered trademark; and (5) the mark must have distinctive character throughout the European Union.

The ultimate outcome for Louis Vuitton’s Damier Azur has yet to be seen. The General Court’s decision, however, was widely considered to highlight “the challenges facing owners of trademarks that consist of fairly basic or commonplace patterns,” as Fieldfisher’s Amy Reynolds put it at the time, noting that “there is a high risk that these types of marks will be considered to lack inherent distinctiveness,” which means that it is usually necessary to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness through widespread and consistent use in order to achieve (and maintain) registrations for these marks, something that brands across the board should keep in mind.