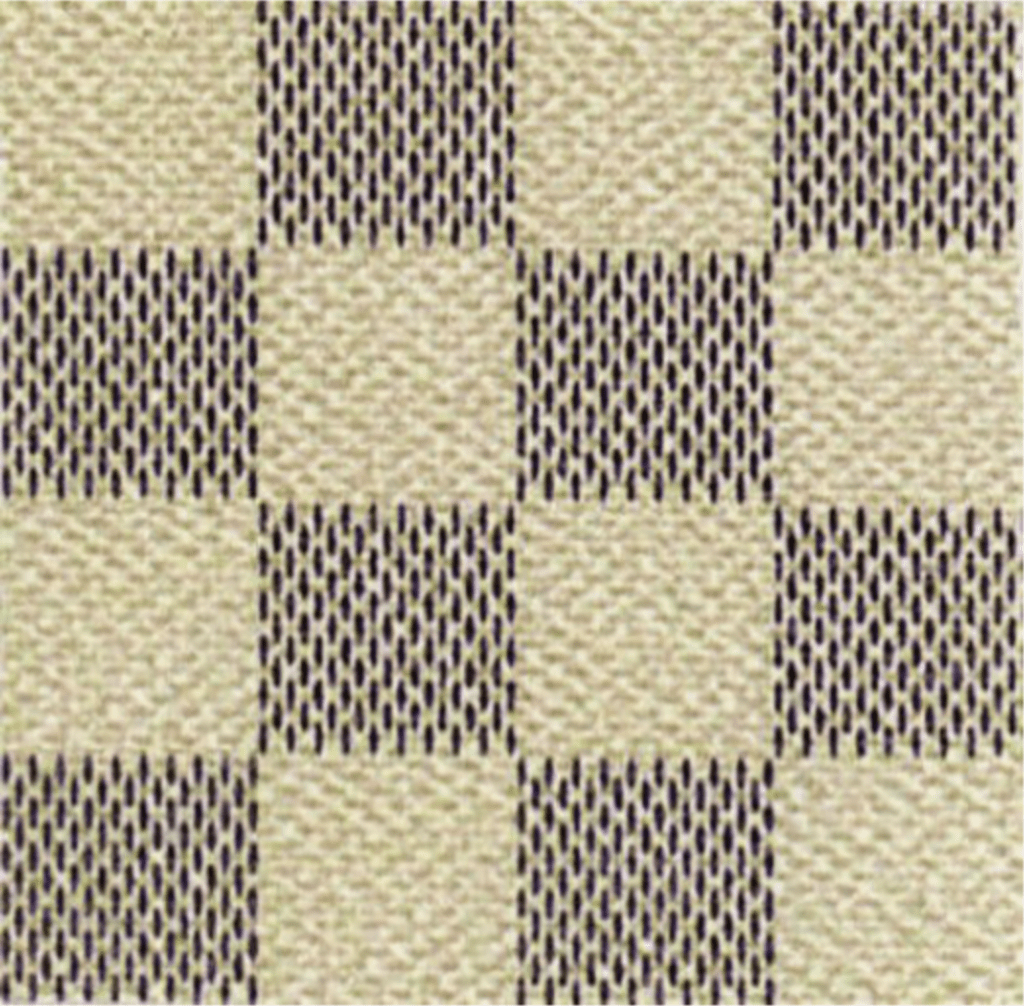

In 1888, a French luggage maker began putting a canvas checkerboard print on its travel goods – a “distinctive checkered pattern of light and dark colors” meant to indicate the source of the products and prevent the rampant counterfeiting of its coveted steamed trunks that was underway. That house was Louis Vuitton and the pattern was its Damier, which has been in use since then and “has been one of the biggest successes of Louis Vuitton,” according to the Paris-based luxury goods giant.

With such “a strong and recognizable pattern” at play, as Louis Vuitton characterizes it, one that has spawned an array of additional checkered canvas designs, counsel for Louis Vuitton has looked to trademark offices across the globe to register the mark and claim exclusive rights in it in connection with its use on luggage and leather goods. One such registration has been at the center of a legal battle for the past 5 years, and as of this past week, Louis Vuitton has been handed a mixed decision from the European General Court.

The brand’s fight for its Damier Azur trademark in the European Union started back in June 2015 – 7 years after the mark was registered with the European Union Intellectual Property Office (“EUIPO”) – when an individual named Norbert Wisniewski sought to formally invalidate Vuitton’s mark on the basis that the checkered print lacks the necessary distinctiveness to operate as a trademark (i.e., to identify the single source of the goods upon which it appears).

Following proceedings before the EUIPO and its Board of Appeal, both of which sided with Wisniewski, Louis Vuitton appealed, arguing that the Board of Appeal had made an “incorrect assessment … of the inherent distinctive character of the mark” and also erred in its assessment of acquired distinctiveness of the mark. Among other things, Louis Vuitton’s legal team argued that the evidence provided by Wisniewski in support of invalidating its registration “was sparse and lacked probative value.”

In a decision dated June 10, the EU’s General Court sided with Louis Vuitton, in part, and against it, in part. According to a 3-judge panel for the court, Louis Vuitton’s beige-and-blue checkerboard Damier mark is not an inherently distinctive indicator of source, as it is “a basic and commonplace pattern that did not depart significantly from the norm or customs of the sector.” However, at the same time, the court asserted that the Board of Appeal only examined a small part of the evidence that Louis Vuitton provided to show that its mark has acquired distinctiveness in the EU (meaning that consumers have come to link the pattern with a single source), thereby, opening the door for a finding in its favor.

Inherent Distinctiveness

In discussing whether the Board of Appeal made an incorrect assessment of the “inherent distinctive character” of Louis Vuitton’s Damier mark, the General Court stated that “the mark at issue consists of a pattern intended to … cover the whole of their surface area and thus, corresponded to the outward appearance of the goods.” Citing the relevant case law for such a mark, the court’s panel held that “only a mark which departs significantly from the norm or customs of the sector of the goods and services at issue, and thereby, fulfills its essential function of indicating origin is not devoid of any distinctive character,” and can be protected as a mark.

Against that background, the court held that it was necessary to consider two key things: (1) a procedural issue about what evidence the Board of Appeal may use in determining the validity of a trademark registration – specifically, whether it may consider “well-known facts that the [trademark office’s] examiner might have failed to take into consideration in the registration procedure,” and (2) “whether the fact that the mark at issue [is] a basic and commonplace pattern that [does] not depart significantly from the norm or customs of the sector concerned could be regarded as a well-known fact.”

In rejecting Louis Vuitton’s bid to overturn the Board’s decision in terms of inherent distinctiveness, the General Court held that the Board of Appeal may “take into account the existence of well-known facts” – i.e., facts that are likely to be known by anyone or may be learned from generally accessible sources – “that the examiner might have omitted,” and noted that “it is apparent” that the Board did, in fact, take into account “a well-known fact when finding that the mark at issue lacked inherent distinctive character.”

The fact at issue here: “The chequerboard pattern has always existed and has been used in the decorative arts sector, and that it [is] a basic and commonplace figurative pattern that [does] not contain any notable variation in relation to the conventional representation of chequerboards, and therefore, [is] the same as the traditional form of such a pattern, with the result that, even when applied to goods such as those in Class 18, that pattern [does] not differ from the norm or customs of the sector.”

With that in mind and even with “the weft and warp pattern that appears on the inside of each of [Louis Vuitton’s] chequerboard squares, [which] creates the visual effect of interlacing two different fabrics,” the Board found that the mark at issue does not depart significantly from the norm or customs of the sector concerned, and thus, is not inherently distinctive.

The General Court has since determined that “the fact that the Board of Appeal took into account a well-known fact when finding that the mark at issue lacked inherent distinctive character … in in addition to the arguments and evidence invoked by the [Wisniewski] for a declaration of invalidity … is in no way contrary to the rules on the burden of proof.”

In short: it is not improper that the Board considered the “well-known fact” that the checkerboard print that is the basis for its Damier is “a basic and commonplace pattern that [does] not depart significantly from the norm or customs of the sector concerned,” and as a result, found that with “any notable variation in relation to the conventional representation of chequerboards” is not subject to protection without a showing of secondary meaning.

Acquired Distinctiveness

In terms of its argument that “the Board of Appeal erred in its assessment of the distinctive character acquired through use of the mark at issue,” Louis Vuitton asserted that the Board “was required to conduct an overall assessment of all the evidence [that it] submitted … in order to determine whether that evidence, taken as a whole, could establish that the mark at issue had acquired distinctive character through use throughout the European Union,” but failed to do so.

Siding with Vuitton, the General Court held that the brand “filed extensive evidence before the EUIPO” to show that the Damier mark had acquired distinctive character through use throughout the EU (after all, “such a mark can be registered only if it is proved that it has acquired distinctive character through use throughout the [entire] territory of the EU”). The problem? The General court held that “by choosing to examine only a small part of the evidence submitted by the applicant and to disregard the other numerous pieces of evidence, without providing any explanation for that choice, the Board erred in law by making a partial assessment of the evidence in the file before it.”

To be exact, the General Court stated in its decision that “the Board did not at any time assess the entirety of the evidence specifically relating to Estonia, together with the evidence relating to the European Union as a whole or to a region of the EU (for example eastern Europe) which may also be relevant to Estonia.”

With the incomplete review by the Board in mind, the General Court annulled the decision of the Board, and has enabled the Louis Vuitton registration to remain in force, while ordering the EUIPO to pay the costs associated with the proceedings. As for what comes next, the EUIPO could appeal the decision to the EU’s highest court, the Court of Justice. Otherwise, the matter will go back down to the EUIPO’s Board for further review.

*The case is Louis Vuitton Malletier v. European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), T‑105/19.