Sephora has managed to escape a lawsuit accusing it of misleading consumers by way of its marketing of “clean” beauty products. In a newly-issued decision and order, Judge David Hurd of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of New York granted Sephora’s motion to dismiss the false advertising, fraud, and breach of warranty lawsuit waged against it, finding that based on Plaintiff Lindsay Finster’s proposed class action complaint, the LVMH-owned beauty retailer did not make misleading claims about its “Clean at Sephora” label. This remains true, according to the court, even if Finster believed that “Clean at Sephora” products are “all-natural or free of any harmful ingredients” and bought them for that reason since Sephora made no such allegations about its “Clean”-branded products.

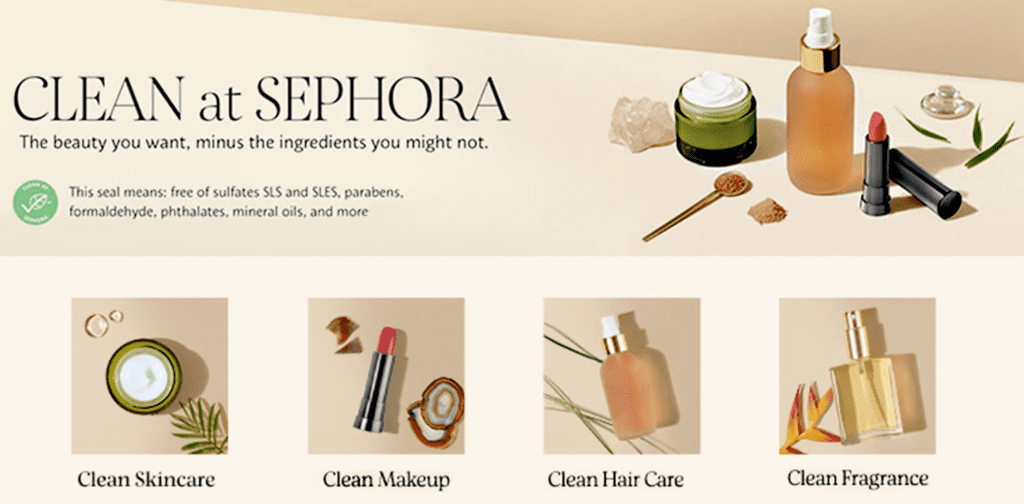

Some Background: Lindsay Finster filed suit against Sephora in November 2022, accusing the retailer of violating New York General Business Law (“GBL”) sections 349 and 350, which prohibit companies from carrying out “deceptive acts or practices and false advertising,” and various state consumer fraud acts, and engaging in fraud, breach of warranty, and unjust enrichment. In the crux of her case, Finster argued that she read and relied on the “Clean at Sephora” seal to believe that cosmetics bearing the seal did not contain any ingredients that were synthetic nor “connected to causing physical harm or irritation.” The problem, per Finster, is that Sephora “made materially false, misleading, and deceptive representations and omissions when it claimed its ‘Clean at Sephora’ cosmetics were ‘clean’” when they contain “synthetic and harmful ingredients.”

Sephora moved for dismissal last year, claiming that it has not marketed, labeled, or sold its “Clean at Sephora” cosmetics as being “all-natural or free of any harmful ingredients.” While its marketing of the cosmetics is straightforward, Sephora maintained that Finster “is intent on twisting words for litigation purposes to mean something other than what they say or are said to mean.”

In an order dated March 15, Judge Hurd sided with Sephora on all of Finster’s claims, finding primarily that her New York General Business Law allegations “fall short of the objective standard imposed on GBL section 349 and 350 claims,” which requires that the conduct at issue be likely to mislead “a reasonable consumer acting reasonable under the circumstances.” Finster pointed to advertising language in which Sephora stated that “consumers who see the Clean seal can be assured that the product is formulated without specific ingredients that are known or suspected to be potentially harmful to human health and/or the environment,” Judge Hurd held. But she did not allege that Sephora made “any claim that the products are free of all synthetic or harmful ingredients.”

Moreover, Finster pointed to “a laundry list of synthetic ingredients found in ‘Clean at Sephora’ cosmetics that she claims have been known to cause irritation or other human harm,” according to the court. Yet, she did “not allege that these are the same ingredients that Sephora claims are not found in its ‘Clean at Sephora’ cosmetics.”

Taking issue with Finster’s breach of warranty claims, the court found that Finster could not identify any “express or implicit fact or promise by Sephora that its ‘Clean at Sephora’ cosmetics were free of all synthetic or harmful ingredients,” thereby, causing her claims under the New York Uniform Commercial Code and Magnuson Moss Warranty Act to fail. At the same time, Finster’s fraud claim is also deficient because she “has not identified a material, false statement,” and therefore, “has not plausibly alleged that Sephora made material, false statements or intended to defraud consumers.”

With the foregoing in mind, the court dismissed Finster’s complaint in its entirety, but granted her leave to amend it by March 29.

Delving into “Clean,” “Green” Definitions

A seemingly straightforward result, the court sided with Sephora in large part because it alerted consumers of what exactly its use of the “clean” marketing language means and its products do not appear to diverge from that meaning. The court was not persuaded by the fact that Sephora defined “clean” in connection with its products (i.e., products that are “formulated without parabens, sulfates SLS and SLES, phthalates, mineral oil, formaldehyde, and more.”) in a way that differs from how Finster defined it (namely, products that do not contain any ingredients that were synthetic nor “connected to causing physical harm or irritation.”).

In finding that Sephora did not mislead consumers by way of its marketing of products under the “Clean by Sephora” label, the court seemed to acknowledge (and be ok with the fact) that there is not one, universally-accepted way of defining “clean” when it comes to cosmetics and that as long as a retailer does not make false and/or otherwise misleading statements in connection with its own product marketing, it will be in the clear even if that definition differs from others’ definitions. In other words, as long as companies are abiding by the definitions they adopt for these terms (and presumably, can substantiate any corresponding claims), their marketing will be above board.

This is meaningful both for the term “clean,” which is widely used among beauty companies; it also has broader significance in light of the fact that many of the widely-touted “eco” marketing buzzwords, such as “sustainability,” “environmentally-friendly,” “green,” etc. lack concrete definitions, and thus, have been used in a variety of different ways by marketers. (It will be interesting to see how such cases are impacted by the impending revision of the Green Guides by the Federal Trade Commission, which has been called by stakeholders to provide more guidance on – and potentially, concrete definitions for many of these buzzwords.)

The Latest “Greenwashing” Win

The positive outcome for Sephora follows from a “green” marketing win for H&M in May 2023 when a federal court in Missouri found that a couple of class action plaintiffs failed to allege that the fast fashion giant engaged in false advertising by way of its Conscious Collection marketing. In that case, the court held that, among other things, the plaintiffs argued that H&M’s Conscious collection-centric labeling and advertising is “false, misleading, and deceptive’ [because it] tricks consumers into thinking that ‘the products are more sustainable.’” However, the court ultimately found that H&M “does not represent that its products are ‘sustainable’ or even ‘more sustainable’ than its competitors. Instead, H&M states that its Conscious collection garments “contain ‘more sustainable materials’ and that the line includes ‘its most sustainable products.’”

In fact, the court held that H&M “actually tells its consumers … that ‘fashion has a huge impact on the environment,’” and that“no reasonable consumer would understand [its] representations” – including that “each Conscious Choice product contains at least 50% more sustainable materials, like organic cotton or recycled polyester” – to mean that the Conscious clothing line “is inherently ‘sustainable’ or that H&M’s clothing is ‘environmentally friendly’ when neither of those representations were ever made.” Instead, the “only reasonable reading of H&M’s advertisements is that the Conscious collection uses materials that are more sustainable than its regular materials,” Judge Rodney Sippel of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri held.

Taken together, these cases indicate that courts appear to be focused on the claims that marketers are actually making, particularly when they provide specific language to define their use of terms like “clean” or qualifiers, such as “more sustainable,” to limit otherwise inaccurately broad readings of such terminology, and not the impression that consumers may garner from such advertisements. This is good news for advertisers.

The case is Finster v. Sephora USA Inc., 6:22-cv-01187 (NDNY).