“Do influencers need to tell audiences that they’re getting paid?” That is the question that two marketing professors posed recently in reflecting on the rise of the $8 billion-plus influencer economy. While it is well-established that the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) requires that influencers – ranging from big-name celebrities and Instagram-famous figures to small-scale micro and nano-influencers – “clearly and conspicuously” disclose when their posts are the result of a “material connection” with a company that consumers might not expect, proper disclosure is hardly a uniform practice.

The number of disclosure-less or proper disclosure-less posts on Instagram, for example, is staggering. Yet, while advertising watchdogs in the United Kingdom, for instance, are increasingly cracking down on influencer behavior, and while the FTC seemed to be upping its activity in this regard when it sent two rounds of letters to fashion brands, celebrities, and a small number of influencers, there has ultimately proven to be little deterrent for brands and influencers when it comes to proper disclosure.

In light of the continued rule-breaking by brands, influencers, and media entities, alike, when it comes to disclosing “material connections,” professors Alice Audrezet of the the Institut Supérieur de Gestion in Paris, France and Karine Charry of the Louvain School of Management in Belgium recently took on the looming question of whether or not influencers really need to make their #partnerships crystal clear for consumers, and whether or not such knowledge – or lack thereof – actually impacts consumer behavior.

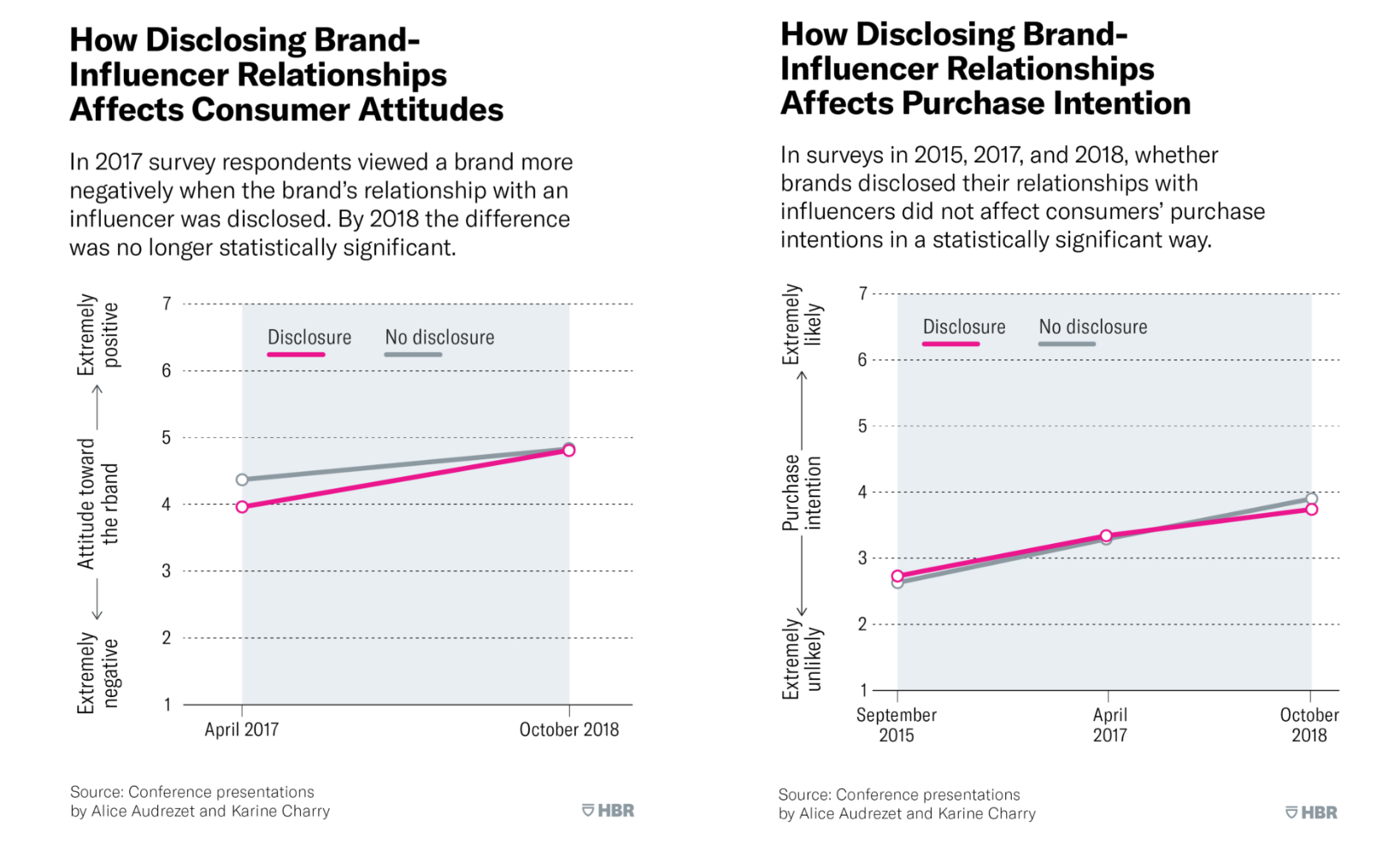

What the two academics found is interesting: consumers’ attitudes towards brands when they see that “the brand’s relationship with an influencer is disclosed” are virtually the same as when that relationship is not disclosed. And the same goes for influencers. “Survey data on influencer trustworthiness mirrors these findings,” as well, Audrezet and Charry assert.

Even more striking that the seeming neutrality amongst consumers when it comes to disclosures is what Audrezet and Charry found when they focused specifically on the actual effects of proper disclosures on consumers’ purchasing intentions. Again, there was little difference. Based on surveys evidence, which was collected between 2015 and 2018, Audrezet and Charry determined that consumers’ purchasing decisions are increasingly informed by influencer endorsements, and that “disclosure makes almost no difference to the impact of the influencer’s recommendation” or endorsement of a product.

These findings stand in stark contrast to the reigning belief among many marketers that disclosure will impede the appeal of what would otherwise appear to be entirely authentic endorsements. They also seem to be at odds with the largescale and enduring practice of companies of requesting that influencers omit disclosure language from their posts entirely, or that they make use of language or the placement of language that would fall outside of the scope of that the FTC deemed to be proper (think: disclosure hashtags hidden amongst other hashtags, disclosure language below Instagram’s “more” button and ambiguous language, such as #ThankYou or #Ambassador).

Audrezet and Charry found that some “28 percent of influencers were requested by sponsoring brands not to disclose the partnership” in order to put forth an image of authenticity.

Interestingly enough, while the lack of disclosure language may have fooled consumers in the past into believing that influencer content is devoid of brand involvement, that belief is arguably outdated even in the relatively new world of influencer marketing. In fact, some 88 percent of the consumers that Audrezet and Charry surveyed believed – as of late 2018 – that influencers commonly recommend brands or products because they are compensated in some way to do so.

In a market in which influencer and brand (and also, brand and the media) tie-ups are the norm, the need for and the reasons for disclosures might be shifting.

For one thing, the rising consumer understanding that influencer activity is generally compensated in some way could stand to impact the need for disclosures, since the FTC only requires that partnerships or connections that the average consumer “might not expect” be disclosed as such. If everything is assumed to be bought-and-paid-for, the need for #ad is likely to diminish. As for whether the FTC is likely to call off its dogs from a disclosure stand point any time soon is unlikely for a number of reasons, including the fact that influencer content inevitably consists of sponsored and non-sponsored content, which, is often indistinguishable to the average consumer, thereby, creating the need to specify which posts contain advertising messages and which do not.

But the more compelling shift is the one that is likely happening as a direct result of consumer expectations. According to Audrezet and Charry, “Savvy consumers are actually valuing the perceived transparency and authenticity of influencers who volunteer a disclosure” (and brands that actually allow it), as opposed to the ones who simply opt out. In fact, in at least some instances, disclosure language confers benefits not just to the influencer but the brand, as well. Given the growing consumer understanding of the prevalence of paid-for or otherwise compensated posts, “disclosure has become a positive signal” to many consumers, per Audrezet and Charry.

Add to that the fact that young consumers are quite different from their older purchasing predecessors. Millennial and Gen-Z consumers are demanding more from brands, whether that be in terms of environmental efforts or in the form of general transparency about their operations. With this has come a rising consumer distaste for shady brand and influencer dealings – including the practice of brands, such as Sunday Riley, allegedly requiring their staffers to post fake reviews in order to boost the appeal of the brand’s products in the eyes of consumers and thereby, lead to higher sales.

With that in mind, the question might be shifting from whether influencers really need to disclosure when they are being compensated (legally, they do) to whether it is in their best interest (and a brand’s best interest) or whether it could serve as a value-add from a consumer perception standpoint to disclosure when they are being compensated. As such, it seems as though influencer disclosure is becoming less of just a legal issue and one that could see more brands adapting in order to meet increasingly-stringent consumer expectations of what constitutes fair – and thus, appealing – advertising.