Celebrities and social media stars have been promoting and selling products in a livestream capacity on their own accounts for years in China, with heavily-followed figures like Tao Liang – who is better known as Mr. Bags – helping to sell upwards of $500,000 worth of Tod’s bags in a matter of minutes as part of a partnership with the brand back in 2018. A year later, Kim Kardashian West appeared on a Tmall livestream with Chinese mega-influencer Viya Huang and sold out her perfume stock to an audience of 13 million viewers in less than 15 minutes, marking another one of many examples of the critical role that livestreaming has played in China’s robust e-commerce economy.

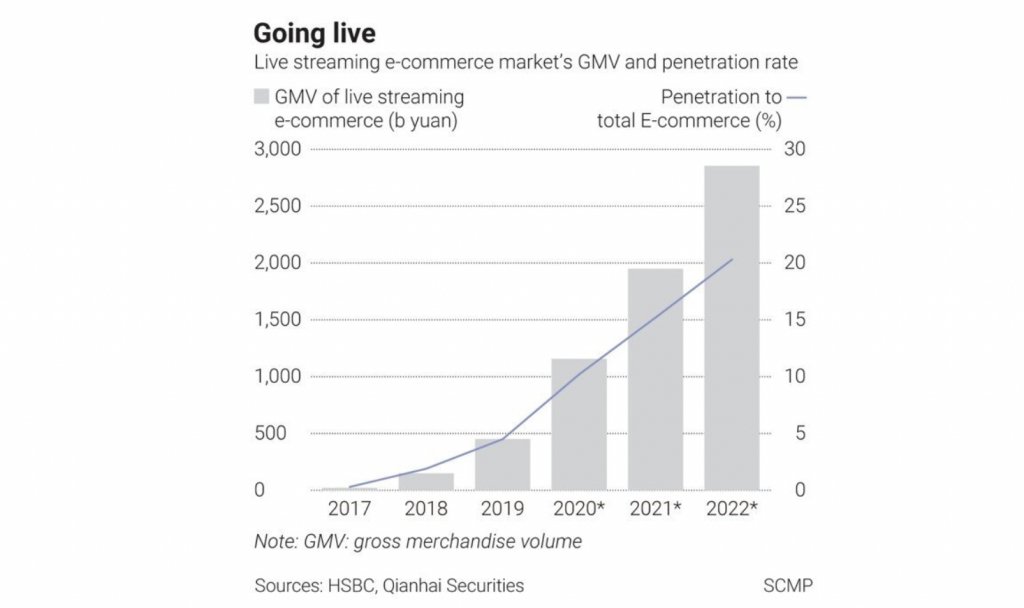

Fast forward to 2021, and livestream e-commerce has “become essential to marketing in pandemic-era China,” according to Chinese tech site TechNode. Against that background, major e-commerce and video platforms – from ByteDance’s Douyin and Alibaba’s Taobao Live to Tencent-backed Kuaishou – have looked to the field as a way to reach consumers and boost revenues, and have emerged as leading players in the process. Alibaba, alone, sold more than $60 billion in merchandise via livestream in 2020 by way of its Taobao Live platform, up by roughly 50 percent compared to the year before. All the while, livestream-generated e-commerce revenues represent an estimated 10 percent of China’s e-commerce market in 2020, according to HSBC and Qianhai Securities, and could account for as much as 20 percent of the market by 2022.

Regulation Rollouts & Legal Battles

With such striking reach and growth in mind, authorities are – unsurprisingly – paying increased attention. This spring, for instance, the Cyberspace Administration of China, along with other key Chinese government entities, such as the State Administration for Market Regulation, enacted new rules for this burgeoning aspect of the e-commerce economy. Enacted in May, the rules require livestreaming sales platforms to take an array of steps to protect users’ rights and combat increasingly pervasive issues – from false advertising and the sale of counterfeit goods to a large-scale lack of consumer data protection mechanisms and a dearth of standardized oversight when it comes to the use of such platforms by individuals under age 16, which is prohibited by law in China.

At the same time as regulators implement heightened rules for this ever-growing segment of the market, livestream-centric legal battles are starting to land in court. In what is being called a first-of-its-kind case, a Chinese livestream platform has been given similar treatment as a traditional e-commerce site in connection with a trademark squabble between two Chinese brands. According to the complaint that it filed in the Beijing Haidian Court last year, Saishi Trading Co., Ltd. (“Saishi”) accused Laizhou Hongyu Arts & Crafts Co., Ltd. (“Laizhou Hongyu”) of selling handbags containing the “AGATHA” trademark and logo on the Douyin livestreaming platform. In its recently-issued decision, the court found that Laizhou Hongyu’s use of the AGATHA mark and lookalike logo on similar goods, namely, bags, ran afoul of the Trademark Law of the People’s Republic of China.

Of particular importance for the court in its determination is the fact that Douyin – whose parent company Bytedance was named as a defendant in the case – essentially operates as an e-commerce entity, despite its video-sharing roots. (Douyin is the Chinese version of the popular short-video sharing app TikTok.) As multi-national law firm Rouse stated in connection with the case, the court pointed out that “Douyin users can directly check order information for the goods they purchased in their [Douyin] accounts and need to click the shopping cart in the interface to enter the store and complete the transaction when watching the live broadcast.” This is significant, according to the court, which held that “Douyin is an e-commerce platform, and thus, Bytedance, as the operator of the Douyin platform, can be considered an e-commerce platform operator” in the eyes of the law.

Bytedance ultimately managed to escape liability. While Douyin has a clear e-commerce integration, which gives consumers the ability to purchase products, including the infringing handbags, within its app, the court found that Bytedance had performed “timely pre-audit, prompting, and disposal measures,” and thus, determined that the Beijing-based internet company had fulfilled its reasonable duty of care in connection with the advertising and sale of the infringing goods on its platform. The court ordered Laizhou Hongyu to pay RMB 300,000 ($46,300) in damages and RMB 10,598 ($1,630) in expenses to Saishi.

Ultimately, the case is a noteworthy one, per Rouse, as it is the first time that a livestreaming platform has been recognized as an e-commerce platform, and also is the first case to do so since the Cyberspace Administration of China implemented of the Trial Measures for the Administration of Live Streaming Marketing rules in May.

The Lure of Live

As for the allure of livestreaming, AgencyChina states that in addition to viewers being able to see products in action, something that is “particularly helpful for a number of product categories, such as color cosmetics and clothes, for which size, color and effect are not as easily discerned from stock photos or videos,” and being able to interact with hosts and ask questions about products in real time, a big draw comes by way of the livestream hosts, themselves, who are often celebrities or key opinion leaders (“KOLs”) that bring with them dedicated fanbases eager to purchase products that they endorse. Beyond that, a key driving force behind the success of livestream-related sales is a host’s ability to “carefully curate their product selections to their fans’ tastes.” This tends to result in especially “high conversion rates,” AgencyChina contends, noting that Alibaba-owned Taobao, which has upwards of 4,000 livestream hosts as part of its KOL ecosystem, has boasted that its conversion rate across livestream “is an astonishing 32 percent.”