Lululemon has responded to Peloton’s declaratory judgment action with a counter suit, arguing that the New York-based exercise bike-maker is on the hook for design patent and trade dress infringement in connection with its sale of “copycat” athleticwear on the heels of pulling the plug on the parties’ 5-year-long co-branding partnership. According to the complaint that it filed in a California federal court on Monday, Lululemon claims that “unlike innovators such as [itself],” when Peloton opted to launch its own collection of apparel, it “did not spend the time, effort, and expense to create an original product line, [and] instead, Peloton imitated several of lululemon’s innovative designs and sold knock-offs of lululemon’s products, claiming them as its own.”

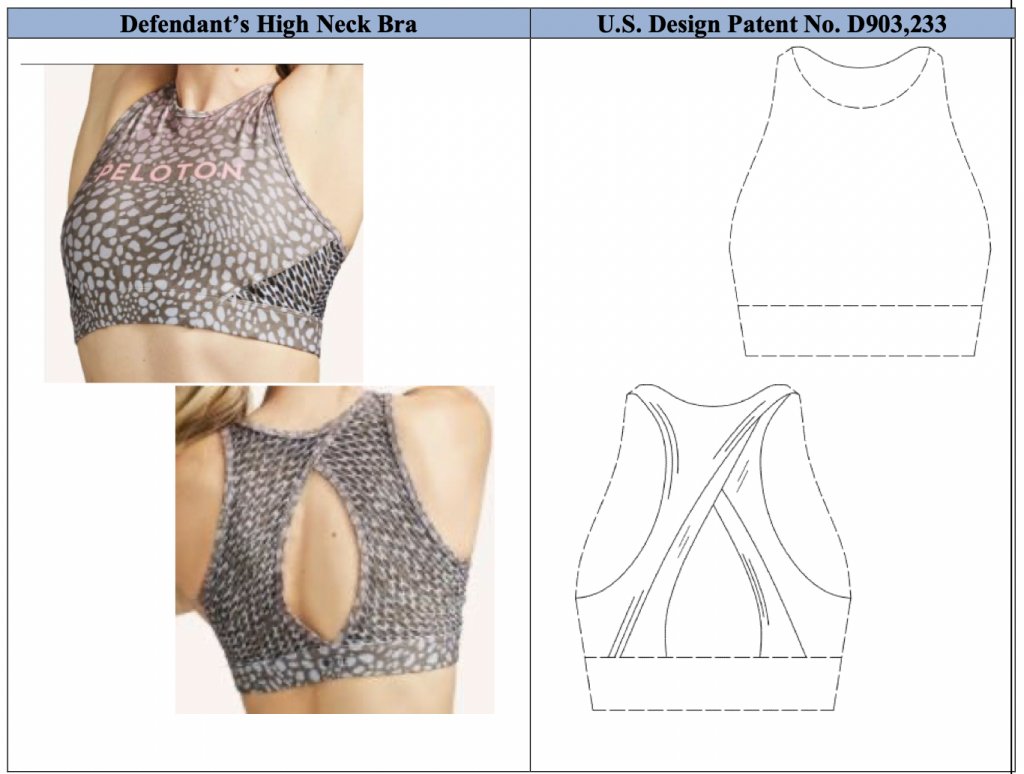

In the newly-filed complaint, much of which mirrors the cease-and-desist letter than it sent to Peloton on November 11, Lululemon alleges that Peloton’s Strappy Bra, Cadent Laser Dot Legging, Cadent Laser Dot Bra, High Neck Bra, and Cadent Peak Bra collectively infringe six different Lululemon design patents. Beyond that, Lululemon claims that Peloton’s One Lux legging is “another imitation of a lululemon product, as it copies the trade dress of lululemon’s Align part, which is one of [its] all-time best-selling products.”

Reflecting on the unregistered Align trade dress, which it rather vaguely describes as including but not limited to “a pair of tight athleisure pants having a waistband and stitching,” Lululemon argues that because the trade dress – a type of trademark protection that extends to the configuration (design and shape) of a product or its packaging – has “established strong secondary meaning and extensive goodwill,” the general public “has come to recognize and identify pants bearing the Align Trade Dress as emanating from lululemon.” In other words, Lululemon claims the configuration of the pants, which is not functional and for which there are “numerous alternative shapes and designs,” have come to act as an indicator of source for its brand.

As such, Lululemon claims that Peloton’s use of the Align trade dress “in connection with products identical to lululemon’s products and sold to the same customers through overlapping channels of trade is likely to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive as to the affiliation, connection, or association [between itself and] lululemon.”

Peloton has, of course, already pushed back against this claim in a trademark capacity in its suit (pretty convincingly, I would argue), asserting that because both companies’ well-known branding appears – in some cases, quite prominently – on their respective offerings, consumers are not likely to be confused at all. (This point could also be relevant from a design patent infringement perspective in light of the Federal Circuit’s holding in the Columbia Sportswear v. Seirus case, which “suggests that logo placement can be an important factor in assessing design patent infringement, particularly when the logo is an integral part of the accused design. In light of this, an infringer could potentially avoid infringement through logo placement on the allegedly infringing design.”)

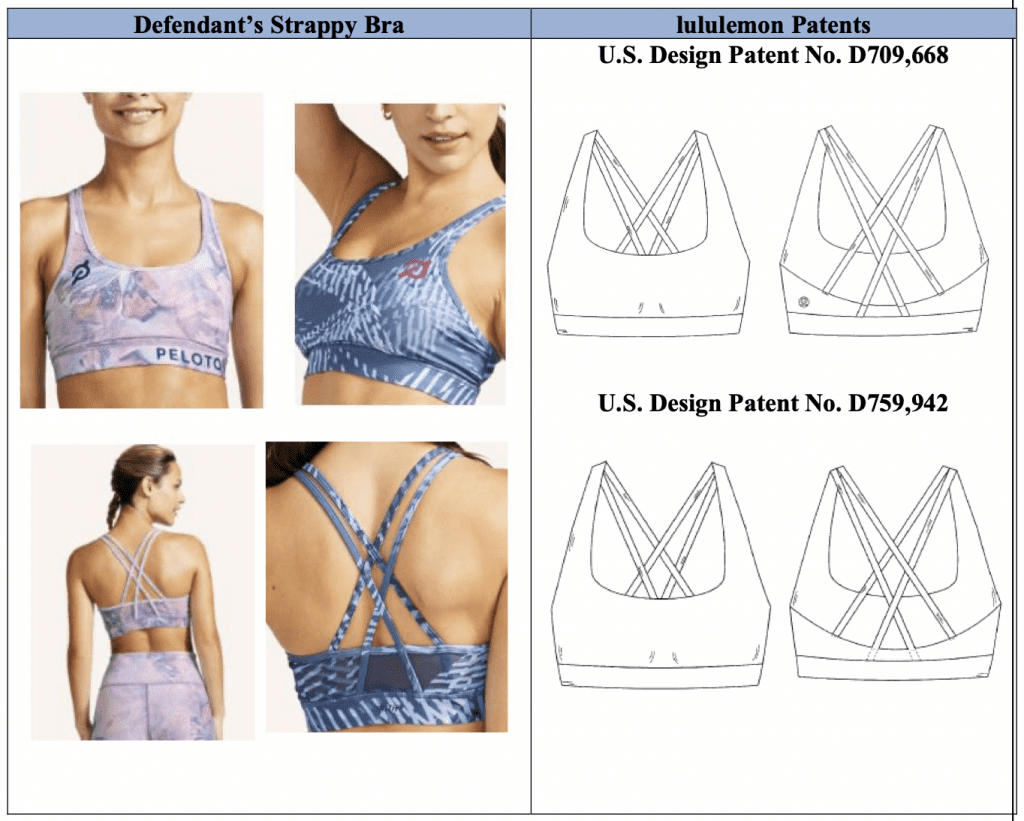

As for its design patent infringement claims (at least some of which appear to be somewhat weak in light of differences between the elements specified in the Lululemon patents and the actual Peloton designs), Lululemon alleges that Peloton has infringed its D709,668; D759,942; D798,539; D836,291; D903,233; and D923,914 patents, which extend to the ornamental elements of a number of sports bras and one that protects elements of its Cadent Laser Point leggings. (Note: design patents are distinct from utility patents, as they protect the overall visual appearance of an article of manufacture, whereas utility patents provide protection for the functional aspects of an article, such as the way an article works and is used.) Lululemon argues that Peloton “has, and continues to, knowingly, intentionally, and willfully infringe” its patents by making, using, selling, offering for sale, and/or importing products having a design that is substantially similar to the claimed design” embodied in those patents.

Pointing to Peloton’s Strappy Bra, for instance, Lululemon contends that “in the eye of an ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives” – which is the standard for determining design patent infringement – “the design of Defendant’s Strappy Bra is substantially similar to the claimed designs of each of the D668 and D942 patents … because the resemblance is such as to deceive such an observer inducing them to purchase one supposing it to be the other.”

In addition to design patent and trade dress infringement, Lululemon also sets out claims of false designation of origin and unfair competition under California Business & Professions Code, and is seeking preliminary and permanent injunctive relief and monetary damages. The company is also seemingly seeking to have a say in the venue where the cases – which will almost certainly be combined into one proceeding given that they are based on the same facts and involve the same parties – will be heard.

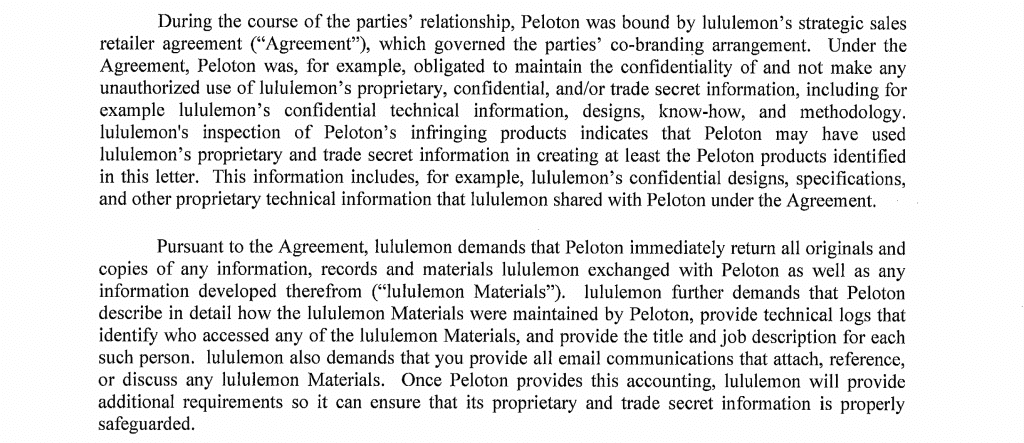

While Peloton filed suit in the Southern District of New York last week, Lululemon has since initiated its case in the Central District of California. Per Lululemon, by filing suit in New York, Peloton has attempted to “improperly wrestle away Lululemon’s choice of forum.” Specifically, Lululemon asserts that after receiving its cease-and-desist letter earlier this month, Peloton requested “more time” to respond to Lululemon’s demands, which Lululemon says that it granted “as a good corporate citizen and out of consideration for the request of a former partner.” However, since Peloton opted to file its declaratory judgment matter “instead of substantively responding to Lululemon’s letter,” Lululemon argues that “it is not clear that Peloton’s request for an extension was not made in good faith” and was actually just a play for venue.

And one final thought on Lululemon’s complaint, it is worth noting the potential that trade secret claims to come into the mix. In the cease-and-desist letter that it sent to Peloton, Lululemon hinted at trade secret misappropriation claims (the relevant language is below), but does not actually include such claims in its complaint.

A Larger Legal History for Lululemon

The now-rival lawsuits are not without history, either for the Lululemon brand or for the sportswear/activewear industry more generally. While the fashion industry sees its fair share of lawsuits, the footwear and sportswear markets tend to be particularly rife with design-specific litigation and other legal conflicts (oftentimes much more so than its fashion counterparts) for a number of reasons.

High on that list is the fact that sportswear/activewear giants like Nike, adidas, Lululemon, etc., routinely invest large sums and years of time in the research and development that goes into their offerings, both from a technical perspective but also in terms of appearance elements. The level of R&D that goes into making things like sneakers and even sports bras gives rise to incentives for brands to “defend [those investments] in innovation” (and thereby, recoup their R&D expenditures), as Nike put it in the design patent infringement lawsuit that it filed against Puma 2018, in which it accused Puma of “forgoing independent innovation and instead, using Nike’s technologies without permission.” It also motivates brands “to protect [their] technologies.”

At the same time, brands appear to be increasingly eager to clamp down on perceived copycat products by way of infringement lawsuits – including ones that center on design patents, which give brands grounds to take legal action when their products or even just individual, protected elements of the products are copied – as competition heats up in the activewear market, which is expected to reach $439.17 billion by 2026, up from roughly $353.5 billion in 2020.

Lululemon is no stranger to litigation stemming from the dozens of design patents that it maintains. The activewear company has been embroiled in a number of high-profile design patent infringement lawsuits over the past decade or so, including with Calvin Klein, Inc., Hanesbrands, and Under Armour, in which similar defensive “obviousness” arguments have been made in connection with Lululemon’s arsenal of design patents. “What Lululemon is doing here is staking its turf,” Jeremy de Beer, a law professor at the University of Ottawa, said back in 2017 when Lululemon named Under Armour in a since-settled suit for design patent infringement. “The business strategy is to deter other people from even trying to copy designs, because it is going to cause them legal problems.”

The same approach is still seemingly being applied by players across the sportswear/activewear industry, all of which maintain robust arsenals of design patents (and in many cases, utility patents, as well) in order to aggressively protect their products against copycats – and maybe more importantly, to protect their position in the market from competitors.

The case is Lululemon Athletica Canada, Inc. v. Peloton Interactive, Inc., 2:21-cv-09252 (C.D.Cal.)