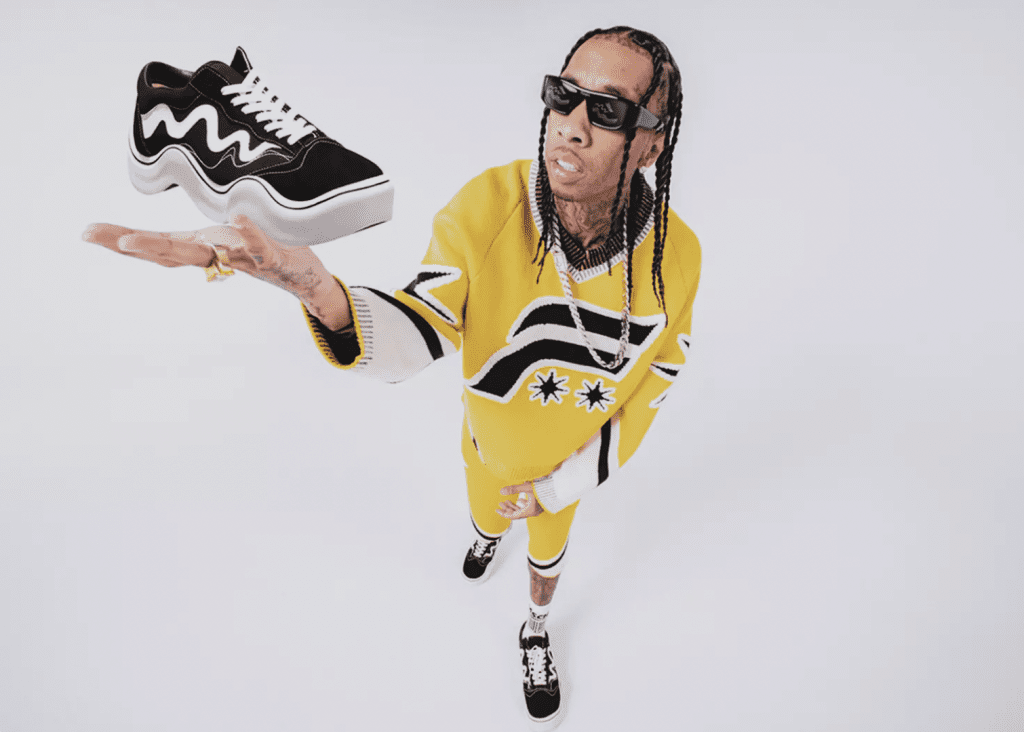

MSCHF and Vans went before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit on Wednesday after the federal court agreed to hear an expedited appeal to the preliminary injunction put in place this spring to block MSCHF from promoting its allegedly infringing Wavy Baby artwork – or sneakers, depending on which party you ask – by displaying the shoes on its website, mobile app, and in art exhibitions, among other things. Counsel for MSCHF, David Bernstein at Debevoise, argued on Wednesday (echoing some of the claims made in the short-lived Satan Shoe case) that the Wavy Babys amount to “expressive works” that are not meant to be worn, but instead, were designed to serve as commentary on sneaker culture and Vans’ role in it, asking the court to consider whether the element of expression or the commercial nature of the sneakers is the predominate factor here.

Appearing on behalf of Vans, Lucy Wheatley of McGuireWoods asserted during Wednesday’s oral arguments that while sneakers may be capable of serving as parodies, that is not what is going on in case that Vans filed suit against MSCHF, in which it is accusing the Brooklyn-based art collective known for its provocative product drops of embarking on “a campaign to piggy-back on Vans’ rights and the goodwill it has developed in its iconic shoes” by offering up a sneaker that “blatantly and unmistakably incorporates Vans’ iconic trademarks and trade dress.” The case, which got its start in April, is being closely watched by brands, academics, and lawyers, alike, for its potential to bring clarity to the murky balance between trademark law and the First Amendment in the context of artistic works.

The panel of judges for the Second Circuit – at least one of which opined that Vans’ side-stripe-bearing shoes might be “the perfect objects of parody to distort” – has been tasked with reviewing the lower court’s decision, along with amicus briefs from a group of intellectual property professors, which focused primarily on trademark dilution, and the International Trademark Association, among others, with the latter urging the Second Circuit to clarify what constitutes an “expressive” work under the Circuit’s Rogers v Grimaldi test.

The parties landed before the federal appeals court following an April order from U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York’s Judge William Kuntz, in which he granted Vans’ motion for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction on the basis that Vans is likely to prevail on the merits of its underlying claims, including trademark infringement, and that the VF Corp.-owned sneaker-maker is likely to suffer irreparable harm unless MSCHF’s alleged infringement is stopped.

In fashioning the injunction order, Judge Kuntz held that “whatever the artistic merits of the Wavy Baby shoes [are],” they “do not meet the requirements for a successful parody,” and sidestepped the application of the Rogers test.

In its answer in June, MSCHF argued that while Vans (and seemingly, the district court, as well) “may not appreciate MSCHF’s critique of [Vans’] place in consumer culture or Vans’ participation in an increasingly digital world,” the Wavy Baby sneakers are, nonetheless, “an expression protected by the First Amendment,” and thus, Vans’ trademark infringement claims not only “lack merit,” but also “fail to account for the expressive message and commentary encompassed in MSCHF’s Wavy Baby artwork.” Citing the U.S. Court of Appeals’ decision in Rogers in its answer, MSCHF claimed that its Wavy Baby project “references Vans’ trademarks and trade dress in an artistic work in a manner that has artistic relevance to the work without being explicitly misleading.”

According to a declaration from MSCHF founder and CEO Gabriel Whaley that was previously lodged with the court, that commentary comes in the form of MSCHF’s attempt to “challenge the sneaker-head culture Vans participates in, question consumerism, and confront the tension between a virtual and digital world” with the sneakers that swiftly sold out this spring.

In the wake of the district court granting a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction for Vans, a move that MSCHF has characterized as an “unconstitutional prior restraint on [its] artistic expression,” the company has reiterated that the Wavy Baby product is clearly an expressive work and should be tested under Rogers. Specifically, counsel for the company has argued that its Wavy Baby project “references Vans’ trademarks and trade dress in an artistic work in a manner that has artistic relevance to the work without being explicitly misleading.”

“Regardless of where one comes out on whether or not the sneakers at issue are expressive works,” Weintraub’s Scott M. Hervey states that, “at a minimum the district court should have engaged in [the Rogers] analysis. The question remains whether the Second Circuit will take this opportunity to establish some guidelines on what constitutes an expressive work.”

The case is Vans Inc. v. MSCHF Product Studio Inc., 22-1006 (2d. Cir.)