Just northwestern of Paris, in a suburban town called Colombes, lies the headquarters of Arkema S.A. Founded in 2004 when French oil giant Total restructured its chemicals business, the global specialty chemicals and advanced materials company is in the business of producing $8.8 billion worth of chemical intermediates like sulfur-based thiochemicals, specialty polyamides (i.e., long, multiple-unit molecules inked together by amide groups), and powder coating resins each year for companies in the fields of auto-manufacturing, big pharma, and agriculture. Also on that list of customers? Major players in the sportswear industry, including Nike.

As it turns out, Arkema has long partnered with Nike – and other sportswear companies – to produce the polymers that can be found in some of their highest performing sports shoes and boots. The largely behind-the-scenes company said in 2018 that it – and its inherently complex chemical offerings, such the bio-based polyether block amide grade that brings “lightness, resistance to bending, and springback” to the construction of Nike’s GS soccer boots – are “quite invisible to consumers.” That, however, might be changing.

After all, the company’s name and one of its high performance chemical compounds are at the center of the controversy that is currently enmeshing Beaverton, Oregon-headquartered Nike: the enduring controversy over the sportswear titan’s superfast Vaporfly 4% sneakers.

Introduced in 2016, Nike’s Vaporfly 4% sneakers began to really raise eyebrows last year on the heels of two remarkable marathon performances. On October 12, 2019, Kenyan long-distance runner Eliud Kipchoge made headlines when he broke the 2-hour marathon barrier at a special event in Vienna. His time? 1 hour, 59 minutes, and 40 seconds. The following day fellow Kenyan runner Brigid Kosgei won the 26.2 mile Chicago Marathon with a world record time of 2 hours, 14 minutes, and 4 seconds.

The most striking commonality between the two record-breaking runners? They were both wearing Nike’s Vaporfly 4% sneaker, a “bouncy, expensive shoe,” as the New York Times describes them, that can increase athletes’ energetic efficiency by 4% or more (hence the numeric element in the name), according to independent and Nike-sponsored studies.

While critics were pondering questions about the $250 Vaporfly sneakers before Kipchoge and Kosgei crossed the finish line in their respective race in October 2019, questions specific to the Vaporfly 4% – which were formally released to the public in 2017 – intensified after Kipchoge and Kosgei’s 2019 races, and have even prompted calls for the International Olympic Committee to decide whether athletes will be permitted to wear the sneakers in the quickly approaching Olympic Games in Tokyo.

Beyond that, the shoes, themselves are coming under the microscope, with many inquiring into what the technology behind the controversial shoes actually looks like.

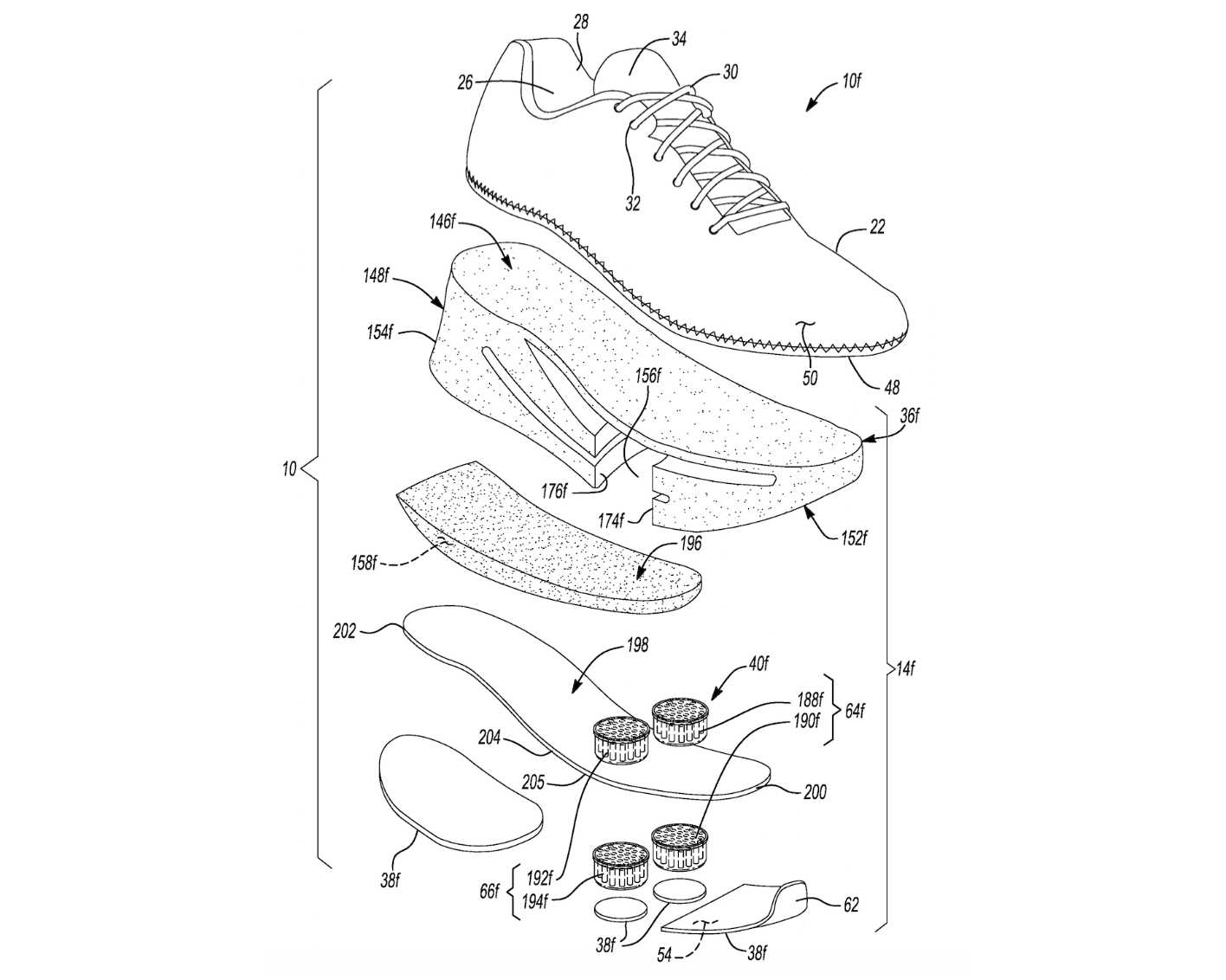

At the heart of the Vaporfly 4% model, as indicated by Nike patent filings – including one that covers a “stacked cushioning arrangement for [a shoe] sole structure” – is a specific combination: two layers of “uncommonly compliant and resilient” midsole foam and a carbon-fiber plate that which helps the foam to compress and expand quickly. Taken together, these elements enable the absorption and recycling of a portion of the energy a runner applies when his/her feet hit the pavement, thereby, creating the “energy savings” that the Vaporfly has become famous for, according to research from the Locomotion Laboratory at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Unlike traditional running shoes, which generally consist of ethylene vinyl-acetate (“EVA”) foam, a compound that “returns about 65 percent of the energy you put into it,” kinesiology researcher Geoff Burns told Business Insider, the Vaporfly is more advanced. Its estimated return-on-energy is a whopping 87 percent. That difference is largely due to the proprietary “midsole foam” that Nike uses, a Peebax compound that it calls ZoomX.

While a handful of Nike inventors (10 to be exact) are named as those behind the creation of the “sole structure” of the Vaporfly 4%, a third party is responsible for one very integral part: the foam. That is where Arkema comes in. The relatively little-known company brings to the table the “closed cell crosslinked foam of a copolymer having polyamide blocks and polyether blocks and a [specific] density” that is Nike’s “lightweight ZoomX foam cushioning.”

The ZoomX foam – which Nike says was “derived from a foam traditionally used in aerospace innovation, applied for the first time in performance footwear in the Nike Zoom Vaporfly Elite and 4% models” – appears to be responsible for a bulk of the success of these record-breaking sneakers, the sneakers that many are saying enable athletes to run “too fast.” Yet, the use of specialized chemical foam is not an entirely new phenomenon. In fact, it was not all that long ago that Nike’s closest rival adidas had the upper hand in what Runner’s World has coined “the race for a breakthrough foam.”

For decades, athletic shoe-makers had relied on EVA, an industry standard compound that was light and provided good cushioning, all while trying to find more attractive alternatives that were not limited by temperature-dependent factors and low energy return, which were a couple of the main downsides of the EVA compounds. “Saucony has tested dozens of foams over the years,” according to Runner’s World, while other companies like Reebok and Under Armour have similarly made strides. Ultimately, though, adidas would prove to be the one to do it.

In furtherance of its quest to make the most comfortable and efficient running shoe the market had ever seen, the German sportswear giant’s Innovation Team enlisted the help of German chemists BASF to create an entirely new foam compound that would “bring together the formerly contradictory benefits of soft and responsive cushioning.”

The result – an expanded Thermoplastic Polyurethane (“TPU”) compound that “was unlike anything that came before” in terms of durability, flexibility, comfort, and energy return technology – is adidas’ wildly popular Boost technology. First released in a commercial capacity in 2013, within two years, adidas was selling 10 million pairs of Boost sneakers in the running category, alone.

In putting Boost-bearing sneakers on the pavement, Runner’s World says that adidas jump-started the “foam wars in earnest,” kicking off what would become an evolving and fierce mission by the world’s largest sportswear companies to put forth increasingly advanced technology, and in the process, actively transform the way athletes compete.

Within a few years of adidas’ Boost hitting shelves, Nike would play its hand: its ZoomX technology. Its new application of the Arkema-crafted Pebax foam – which has technically been around since the early 2000s, with Nike being one of the earliest adopters – would put it back on top. The French chemical company says that the ZoomX foam is as much as 20 percent lighter than TPU-based foams, such as adidas’ Boost, and its capacity to produce “energy savings” is entirety unparalleled.

Not merely ready to sit on the sidelines while its Vaporfly 4% makes headlines (both for being super-fast and for being super-controversial), Nike newest model, the Next% – which it unveiled in the spring of 2019 just ahead of the London Marathon – boasts a midsole that contains 15 percent more foam than its predecessor.

All the while, Runner’s World says that adidas, “which has been a little quiet on the foam front besides tweaked versions of its midsole tech like Boost HD, is rumored to be working on a new shoe that was supposedly tested at the Berlin Marathon [in 2019], and which may be its answer” to its rival’s game-changing move.