Deep Dives

Nike prompted an explosion in trademark filings after it made headlines in October 2021 in connection with a number of trademark applications for registration that it lodged for its famous marks for use on goods/services the virtual world. On the heels of the Beaverton, Oregon-based sportswear behemoth filing an array of metaverse-specific applications for its name, swoosh logo, and various other word marks, hundreds of other companies – from Rolex to Inditex – swiftly followed suit and filed applications of their own for use of their marks in the “quintessential” metaverse classes of goods/services, namely, “downloadable virtual goods” (in Class 9), “retail store services featuring virtual goods” (Class 35), and “entertainment services, namely, providing on-line, non-downloadable virtual footwear, clothing … for use in virtual environments” (Class 41).

The barrage of trademark applications appeared to be motivated largely by uncertainty among brands and their lawyers about how courts and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) (and other trademark offices), alike, would treat their existing trademark rights and registrations in connection with the burgeoning world of Web3. The flurry of filings – almost all of which mirrored the classes and corresponding descriptions of goods/services in the ones lodged by Nike – also seemed to suggest that brands were not quite sure what they are going to do in the metaverse, and thus, their filing were merely a way to cover their bases in advance.

As for the filing basis for such applications (almost exclusively intent-to-use), that was a clear indication that most companies had not yet figured out how they would use or begun to make any meaningful use of their marks in Web3.

Fast forward just over two years and that same theme is proving to be true: the vast majority of the companies that filed applications for registration for use of their marks in the metaverse have not been able to show actual use in the virtual world. This means that in lieu of issuing registrations, the USPTO is handing out notices of allowance, and in many cases, companies are responding by requesting extensions.

One need not look further than a number of Nike applications for registration, including for its Swoosh logo, “NIKE” and “JUST DO IT” word marks, and a stylization of the word NIKE paired with the Swoosh logo. Nike has been granted notices of allowance for these marks, meaning that they have all survived the opposition period and have consequently been allowed by the USPTO. However, they have not been registered since Nike has not yet provided the USPTO with statements of use/specimens for the marks and instead, has sought extensions to (it seems) give it more time to make or claim use of the marks in a Web3 capacity.

Nike is hardly the only company that has been granted notices of allowance for its metaverse marks. Champagne-maker Ace of Spades Holdings, for instance, was granted a notice of allowance in March 2023 for a mark that consists of “a three-dimensional configuration of a bottle in gold with a relief of a stylized spade design with a stylized letter ‘A’ and vine design on the neck of the bottle” for use in connection with “downloadable virtual goods, namely, computer programs featuring crypto collectibles, and digital collectibles authenticated by non-fungible tokens (NFTs) … for use online and in online virtual worlds.”

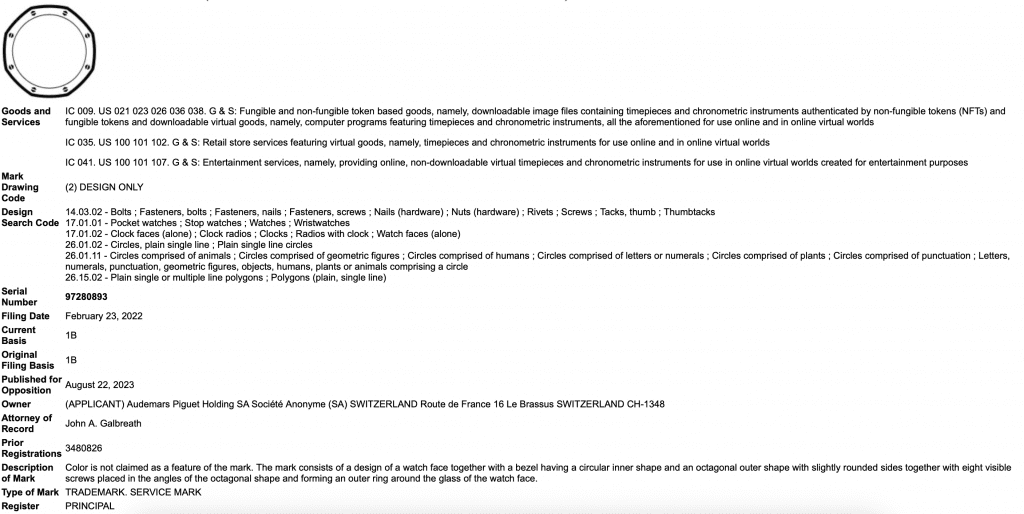

Similarly, Audemars Piguet was granted a notice of allowance for a mark that consists of “a design of a watch face together with a bezel having a circular inner shape and an octagonal outer shape with slightly rounded sides together with eight visible screws placed in the angles of the octagonal shape and forming an outer ring around the glass of the watch face” for use in connection with NFTs (Class 9), “Retail store services featuring virtual goods, namely, timepieces and chronometric instruments for use online and in online virtual worlds” (Class 35), and “entertainment services, namely, providing online, non-downloadable virtual timepieces and chronometric instruments for use in online virtual worlds created for entertainment purposes” (Class 41).

(Note: The notice of allowance, which was issued in October 2023, comes after Audemars Piguet convinced a USPTO examining attorney that its mark does, in fact, function as a trademark to indicate the source of its goods and services and to identify and distinguish them from others. In response to a non-final Office action this spring, the Swiss watchmaker told the USPTO that it “is preparing to use the applied-for mark in commerce for the goods and services listed in the application – and when it does so, it will use the mark as a trademark, so that the consumer will perceive the bezel as a source-identifier and not as an artistic feature of the goods.”)

Ultimately, while trademark registrations for these metaverse marks may bring benefits for brands (particularly, smaller companies with trademarks that are far less famous than the likes of Nike), early indications from courts and the USPTO seem to suggest that metaverse-specific registrations are not necessary – at least not for big brands. Some early intel came by way of the MetaBirkins case, which saw Hermès wage trademark causes of action against artist Mason Rothschild over the unauthorized and allegedly infringing and diluting use of its “BIRKIN” word mark for NFTs.

While Hermès filed intent-to-use applications for registration with the USPTO for its name, along with the BIRKIN and KELLY word marks for use on virtual goods/services in August 2022, it has not (yet) made Web3-specific uses of its marks in a consumer-facing capacity. Nonetheless, the court denied Rothschild’s motion to dismiss Hermès’ trademark claims and a jury subsequently sided with the French luxury goods brand on its three trademark causes of action. The outcome of the case – which is currently the subject of an appeal – seems to suggest that a disconnect does not necessarily exist between companies’ trademark rights in the so-called “real world” and those that exist for similar uses in the virtual world.

In other words, well-known companies appear to be able to rely on their “real world” rights to block unauthorized uses of their marks in the metaverse without the need for new registrations.

The USPTO made similar determinations when it refused to register two unaffiliated individuals’ applications for the GUCCI and PRADA word marks for use in the metaverse even though neither Gucci nor Prada had pending applications or existing registrations for their word marks for use in Classes 9, 35, or 41 at the time. For one thing, the marks were too similar to existing Gucci and Prada registrations to pass muster, according to the Office actions that the USPTO issued in September 2022. Beyond that, the USPTO stated that the “virtual goods, such as footwear, clothing, headwear, eye-wear, handbags, jewelry, and watches” listed in the since-rejected applications are so similar to Gucci and Prada’s physical “footwear, clothing, headwear, eye-wear, handbags, jewelry, and watches” (for which they maintain registrations) that consumers are likely to view them as “emanat[ing] from a single source, under a single mark.”

As such, the USPTO determined that the applicants’ hypothetical virtual Gucci and Prada-branded goods and those that are offered up by the fashion brands, themselves, were related, thereby, adding to the potential for consumer confusion. Those applications have since been abandoned by the filers.

In light of the swift decline of the high hopes that fashion and other industries have had for the promise of virtual world (and the potential to sell trademark-bearing goods there), the significance of these metaverse-specific marks has similarly been diminished. However, in light of efforts by no small number of luxury brands to utilize NFTs and other aspects of blockchain technology to label and then track/trace the lifecycle of physical products, at least some companies’ efforts to register their marks for use in Web3 more broadly are worth keeping an eye on.