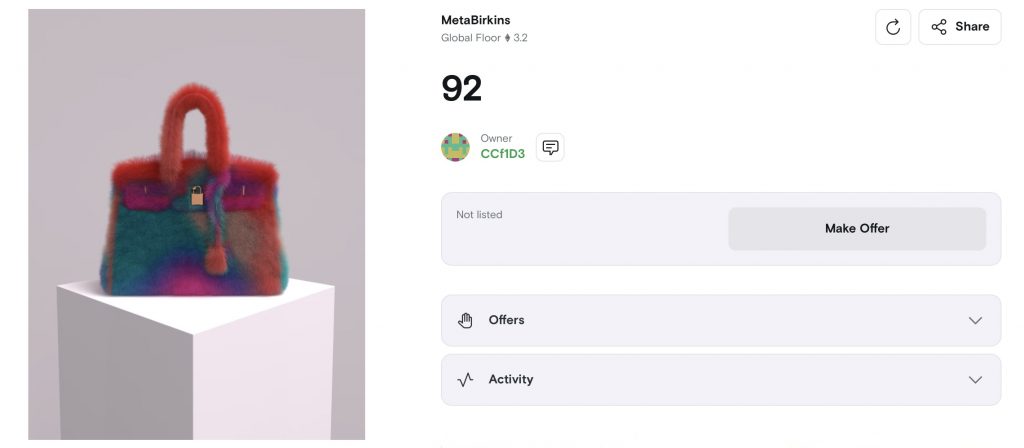

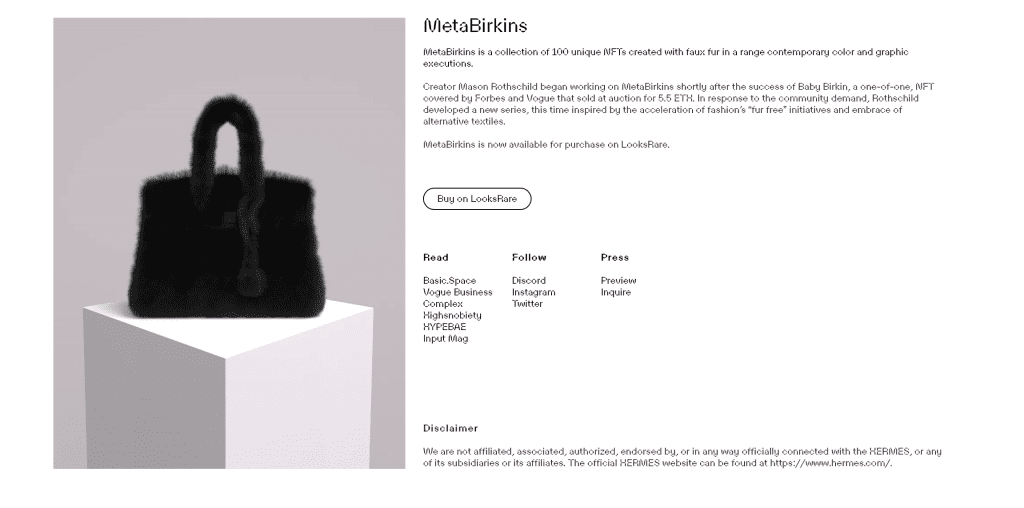

A highly anticipated trial over non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) tied to images that resemble Hermès Birkin bags kicks off in New York today. The MetaBirkins case got its start in January 2022 when Hermès lodged trademark infringement and dilution claims against artist Mason Rothschild, accusing him of “attempt[ing] to capitalize on the goodwill of a leading luxury brand” and its “iconic” Birkin bag by way of a collection of 100 MetaBirkins NFTs. Last year, Judge Jed Rakoff of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York denied Rothschild’s motion to dismiss on the basis that Hermès’ allegations that he was using its trademarks in a way that is not artistically relevant and that the MetaBirkins title “explicitly misled” the public into thinking the NFTs were associated with Hermès, created a factual dispute that could not be resolved via a motion to dismiss. Keeping the case in play, the court set the stage for trial.

The closely watched lawsuit “raises issues of first impression that could set significant legal precedent in the realm of fair use and clarify the balance of free speech and trademark protection as applied in the metaverse and beyond,” ArentFox Schiff’s Yusef Abutouq, Elizabeth Cohen, Michelle Cooke, and Dan Jasnow stated in a recent note. A number of interesting and nuanced issues stand out in the case, particularly in light of efforts by brands and third-party creators, alike, to engage with consumers – and generate revenue – in the virtual world, where the applicability of traditional trademark tenets are being tested in real time. A few of those notable issues (more to come), include …

To what extent do “real world” rights apply in the virtual world?

Primarily, the case highlights the potential (although – unlikely – I think) disconnect between the existence of companies’ trademark rights in the so-called “real world” and those that can be enforced in the web3 realm. Or more specifically, whether Hermès can successfully block unauthorized use of its Birkin mark (which it uses across a variety of “real world” goods/services) in connection with the sale of NFTs. Hermès lacks trademark registrations for its name and Birkin mark for use on digital goods and is not using those marks in the metaverse and/or offering up NFTs tied to its famed bags (yet?), but it is worth noting that the court, nonetheless, denied Rothschild’s motion to dismiss Hermès’ trademark infringement claim.

To make its case for trademark infringement, Hermès needs to show that it has a valid mark (in other words, that its “real world” rights in the Birkin mark extend to the virtual world), and that Rothschild used the same or a similar mark in a way that is likely to confuse consumers. As for where its alleged rights in the Birkin mark for use on virtual goods/NFTs come from, Hermès has argued that offering virtual goods is within its “natural zone of expansion,” particularly given that “fashion brands have entered and are continuing to grow in the metaverse.”

In a note this summer, Fish & Richardson’s Cynthia Johnson Walden and Sarah Kelleher stated that “arguments exist that infringement of trademarks in connection with virtual goods and services should be covered by the ‘natural zone of expansion’ doctrine, meaning that brand owners can rely on existing rights to pursue enforcement.” By way of example, they argue that “consumers shopping for a new Gucci handbag in the virtual world” are likely to assume that a handbag bearing Gucci trademarks is “being offered by (or at least authorized by) the fashion house, meaning such an expansion by the fashion house would be a natural one.”

At the same time, Leason Ellis’ Martin Schwimmer previously told TFL that a company’s “existing trademark portfolio will probably cover the most predictable of their activities in the metaverse.” So, just as Nike does not need to file applications for “shoes sold over the internet,” he said that “they will not need to file for shoes sold via the metaverse.” The same likely holds true for Hermès.

Even so (as indicated by the sheer influx of trademark applications lodged with the USPTO over the past couple of years), brands and creators are in need of clarity, and Michael Best & Friedrich LLP’s Laura Lamansky asserted recently that the MetaBirkins case will “hopefully shed some light on … how far a brand’s rights in its trademarks or products extend in the digital space [and] what artists can and cannot create and render virtually.”

How does the First Amendment/Rogers test apply in the context of NFTs?

Rothschild asserted in a March 2022 motion to dismiss that the MetaBirkins NFTs should be shielded from Hermès’ trademark infringement claim under the Rogers test. The court refused to toss out Hermès claims, with Judge Rakoff determining that there may be an “artistic aspect” to the faux-fur-covered Birkin bag images linked to the NFTs, making the Rogers test relevant. Even so, the judge found that Hermès had sufficiently alleged that even if Rothschild’s use of “MetaBirkins” is “artistically relevant,” his use of “MetaBirkins” may be explicitly misleading as to the source of Rothschild’s artwork and thus, may give rise to Lanham Act liability. (In its complaint, Hermès pointed to Rothschild’s “bad faith” in adopting the “MetaBirkins” mark (including his alleged aim of associating the NFTs with the fame/goodwill of Birkin mark to create and sell his NFTs), and examples of actual confusion among consumers, media outlets, etc. as evidence of explicit misleadingness.)

As such, while the court stated that Rogers is the appropriate test here since Rothschild is “selling digital images of handbags that could constitute a form of artistic expression,” it was unwilling to toss out the case at the motion to dismiss stage. (This comes in contrast to the court’s recent finding in the Yuga Labs v. Ryder Ripps case, in which the United District Court for the Central District of California determined that the “sale of RR/BAYC NFTs is no more artistic than the sale of a counterfeit handbag, making the Rogers test inapplicable.”)

Judge Rakoff’s decision to let the case go forward “was clearly influenced by the commercial nature of Rothschild’s activities, with an eye to potential future sales of virtual goods in a metaverse” (which is something that Hermès has alleged), Gibson Dunn’s Howard Hogan and Connor Sullivan stated in a client alert at the time. The court hinted at some ambiguity on this front, stating in a footnote that First Amendment concerns may not arise with respect to all artistic images associated with an NFT. The court specifically noted that Rothschild “seems to concede” that Rogers might not apply if the NFTs were attached to a digital file of a virtually wearable Birkin, for example, “in which case the ‘MetaBirkins’ mark would refer to a non-speech commercial product.”

The court left the bulk of this issue for a later date, saying in the May 2022 order that Hermès’ “only contention” is that Rothschild might branch out into virtually wearable ‘MetaBirkins.’” In addition to pushing for protection of virtual fashion that is displayable but not wearable (like the MetaBirkins images), Pierce Atwood’s Kasey Boucher and Shannon Vittengl state that they suspect Rothschild “will argue that even virtually wearable items should be afforded First Amendment protection, especially given that video games have received such protection.”

What role do disclaimers play?

It will be interesting to see how the disclaimer that Rothschild includes on the MetaBirkins website is ultimately treated. Hermès has argued that the disclaimer – which reads, “We are not affiliated, associated, authorized, endorsed by, or in any way officially connected with HERMÈS, or any of its subsidiaries or its affiliates” – actually increases the likelihood of consumer confusion as it “excessively” uses the Hermès mark and “unnecessarily” links Hermès to Rothschild’s website. Hermès also insists that the disclaimer is noticeably absent from all other places where the NFTs are promoted and/or sold, including NFT marketplaces and Rothschild’s social media channels.

In response, Rothschild has asserted that the inclusion of the disclaimer on the MetaBirkins site is evidence of his good faith, asserting in an Oct. 2022 memo that he added the disclaimer, which “further demonstrated his explicit disclosure of source [and] reinforc[es] his intent to make art rather than to confuse.”

This is not the only NFT-centric trademark case that involves a disclaimer. In fact, in Yuga Labs v. Ryder Ripps, C.D. Cal. Judge John Walter commented on the disclaimer on Ripps’ site – which states that Ripps is the creator of the RR/BAYC NFTs and that the project uses “satire and appropriation” to criticize Yuga Labs’s BAYC collection – in an order last month. According to the court, although Ripps and co. argue that their “disclaimer … negates any confusion, [they] ignore the fact that they also used other websites to market and sell their RR/BAYC NFTs and those other websites did not include the disclaimer.” Moreover, court stated that “the fact that the defendants felt obliged to include a disclaimer demonstrates their awareness that their use of the BAYC marks was misleading.”

What are the potential impacts?

Finally, as for what we can expect from the parties’ trial, Nixon Peabody’s Valentina Polunina stated that a win for Hermès “would be a victory for all brand owners” in that it would “strengthen brand owners’ right to control the use of their trademarks in the metaverse” – including in the event that they are not currently operating in the virtual world. On the other hand, she contends that creators like Rothchild “would be left with only two main methods of utilizing trademarks in their NFT-linked art: (i) obtaining licenses from trademark owners to use their marks or (ii) take greater efforts to ensure that their artwork does not explicitly mislead as to the source of the work.”

Still yet, a win for Hermès would act as a clear signal that existing trademark tenets can be applied somewhat neatly to the technological advances that are web3. (As for what would happen to the MetaBirkins NFTs, themselves, in such a situation, we dove into that here.)

If Rothschild were to prevail, that would likely embolden creators’ use of others’ marks in the virtual world – to some extent, at least. It could also likely signal more broadly that artworks that are authenticated and sold using NFT technology may have identifiable artistic value (as distinct from the NFTs, themselves) and thus, are not necessarily the “commercial commodities” that Hermès claims that the MetaBirkins are.

Regardless of the outcome, the case is readily being characterized as “a momentous turning point for web3 and digital goods,” and one worth keeping a close eye on.

The case is Hermès International, et al. v. Mason Rothschild, 1:22-cv-00384 (SDNY).