In the only major development in the case that it filed against two influencers and nearly a dozen third-party sellers in connection with an alleged scheme to peddle fakes under the radar of its increasingly robust anti-counterfeiting controls, Amazon has revealed that the parties have reached a settlement. The exact terms of the agreement between Amazon and the defendants are confidential, but do include a prohibition against influencers Kelly Fitzpatrick and Sabrina Kelly-Krejci from “marketing, advertising, linking to, promoting or selling any products on Amazon,” per CNBC, and as for the unspecified monetary damages being paid by the defendants, Amazon will donate the sum to various non-profit organizations, including an anti-counterfeiting initiative of the International Trademark Association.

The newly-announced settlement in the false designation of origin and violation of Washington Consumer Protection Act case that Amazon filed in November 2020 comes as Amazon has been looking to build goodwill with consumers and brands by way of an array of counterfeit-centric lawsuits, including ones that it has filed in conjunction with brands ranging from Italian fashion brand Valentino and beauty company KF Beauty to cooler-maker Yeti. Following years of seemingly ineffective enforcement of its sweeping third-party marketplace, especially following its 2014 decision to boost revenues by enabling China-based entities to sell directly to its members in the West, a move that grew its sales by a whopping 20 percent in a single year and prompted its total revenues to blaze past the $100 billion mark for the first time, Amazon has implemented an apparent mandate to clean up its third-party seller site in light of the striking influx of counterfeit and otherwise infringing goods.

Amazon Aims to Build Trust

One of the most striking indicators of this push came in 2019 when the Seattle-based e-commerce giant made mention – for the first time ever – in its annual 10-K filing of one of the elephants on its platform: fakes. In a single line in the “risk factors” section of the yearly report it files with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, the Jeff Bezos-owned company stated, “We may be unable to prevent sellers in our stores or through other stores from selling unlawful, counterfeit, pirated, or stolen goods, selling goods in an unlawful or unethical manner, violating the proprietary rights of others, or otherwise violating our policies.”

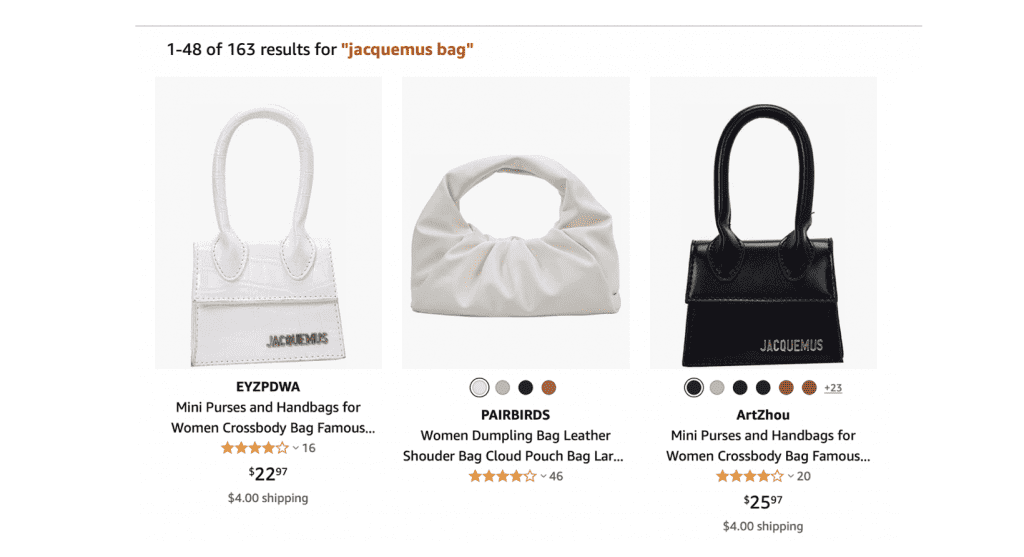

The admission of counterfeit-related risks has come hand-in-hand with a growing (but still relatively small) number of Amazon-initiated trademark infringement suits, such as the one at hand. While Amazon is, in fact, seeking legal and equitable remedies in connection with these often headline-making cases, and while it is aiming to cut down on the sale of (at least some) fakes on its site in the process, it is not difficult to see that the suits serve another purpose, as well: they help Amazon build up awareness around its efforts to rid its site of fakes (despite the relative ease with which consumers can still search and purchase counterfeit goods on the marketplace, such as these “Jacquemus” bags, on Amazon’s marketplace).

One need not look further than the language in any of the complaints that Amazon files to see what appears to be a PR angle at play. There is no dearth of language in the publicly-accessible complaints in these cases, for example, that consists of Amazon outlining the extent of its anti-counterfeiting efforts, often in specific detail, and complete with eye-catching stats about the extent – and success – of its efforts. In the case it filed against Fitzpatrick and Kelly-Krejci, for instance, Amazon asserts that “each week [it] monitors more than 45 million pieces of feedback it receives from customers, rights owners, regulators, and selling partners,” noting that when it “identifies issues based on this feedback, it takes action to address them, also us[ing] this intelligence to improve its proactive prevention controls.”

In a subsequent section, Amazon states that “more than 350,000 brands are enrolled in Brand Registry,” an initiative that provides brands with “a powerful Report a Violation Tool that allows brands to search for and accurately report potentially infringing products using state‐of-the‐art image search technology.” The result? “Those brands are finding and reporting 99% fewer suspected infringements since joining Brand Registry.”

Luxury Ambitions

As TFL has asserted in the past, the Amazon initiatives that are aimed at cutting down on the saturation of its marketplace with fakes – and the push to garner good press in the process – are likely being driven by the retail behemoth’s ambitions in the apparel and luxury space, which call for a certain level of trust by brands and consumers in order for these endeavors to be successful. Look no further than Alibaba and its own PR-heavily revamp as an example of this. (It is worth noting, as we did here, that in addition to its resource-intensive efforts to make inroads into luxury, which included addressing infringement issues, and its years-long media push to reposition itself in furtherance of that goal, Alibaba likely has something else to thank for its ability to lure brands to its site, as well, that cannot be overlooked or undersold: its willingness to concede control to the brands, themselves, to dictate everything from the pricing to the marketing of their products on the Luxury Pavilion site, which is distinct from its main e-commerce platform.)

Given its not-so-secret attempts to infiltrate the luxury space, which are not so dissimilar from Alibaba’s push into luxury, Amazon appears to be using these lawsuits and an array of internal initiatives, such as Project Zero, as a way to chip away at counterfeit-specific scrutiny of its platform both in the minds of consumers and also of potential brand partners.

As for the success of its luxury ambitions to date, the roster for its Luxury Stores, which launched almost exactly a year ago, is up, with 45 brands currently listed. Altuzarra, Aquazzura, Christopher Kane, Missoni, Rodarte, and Oscar de la Renta are among the biggest names. It is also worth noting that Amazon Prime plays host to the viewing of fashion shows for Rihanna’s Savage X Fenty lingerie brand, which undoubtedly helps Amazon to boost its credentials in the fashion space. Despite such gains, though, its Luxury Stores vertical still pales in comparison to other retailers and also its Chinese rival Alibaba, whose 4-year-old Luxury Pavilion boasts brand partners, such as Valentino, Burberry, Versace, Ermenegildo Zegna, Stella McCartney, Tod’s, and Moschino, just to name a few.

The case is Amazon.com, Inc. v. Fitzpatrick et al, 2:20-cv-01662 (W.D. Wash.).