Boohoo, Nasty Gal, and PrettyLittleThing are fighting back against a trio of proposed class action lawsuits accusing them of fraud in connection with an alleged scheme to inflate the original prices of their fast fashion wares in order to “deceive customers into a false belief that the sale prices [that they advertise on their e-commerce sites] are deeply discounted bargain prices.” That is what Farid Khan, Haya Hilton, and Olivia Lee (the “plaintiffs”) argue in the respective complaints that they filed against the Boohoo Group-owned brands this spring.

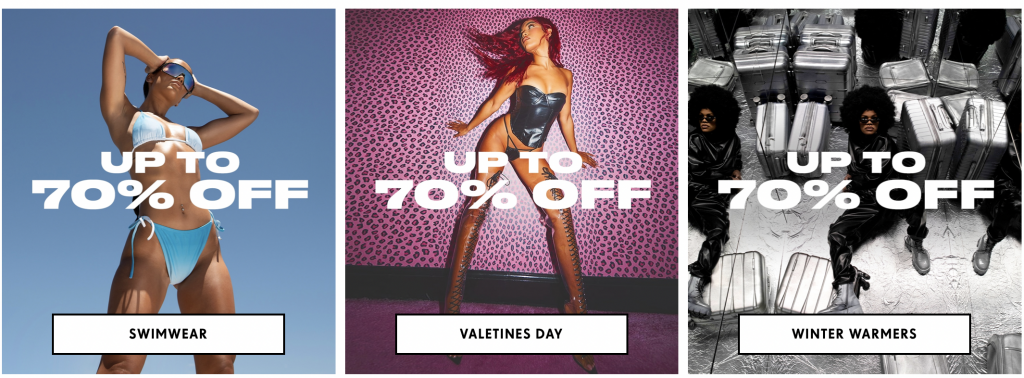

In the since-consolidated suits, all of which were filed in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, the plaintiffs assert that “on a typical day,” the Boohoo brands “prominently display on [their] landing pages some form of a sale where all products or a select grouping of products are supposedly marked down by a specified percentage – for example, 40, 50, or 60% off.” The problem with that, they contend, is that such a “sale” is “not really a sale at all,” and that “all the reference prices on the Boohoo websites are fake” since the retailers never offered up the “sale” garments for their original, pre-sale prices.

Given that the plaintiffs and other consumers have “relied on [the Boohoo brands’] representations that each of the products” that they purchased “was truly on sale and being sold at a substantial markdown and discount” when that was not true, the plaintiffs claim that Boohoo, Nasty Gal, and PrettyLittleThing are each on the hook for damages of more than $5 million for violating California Unfair Competition Law, California False Advertising Law, and California Consumer Legal Remedies Act.

In response to the suits (or more specifically amended versions of the plaintiffs’ complaints), the Boohoo Group brands have filed individual – but basically identical – answers, in which they deny the majority of the plaintiffs’ claims and set out nearly 30 affirmative defenses in an attempt to shield themselves from claims that they are actively engaging in a “scam” in order to “lure unsuspecting customers into jumping at a fake ‘bargain.’”

In the answers that they filed late last week, Boohoo, Nasty Gal, and PrettyLittleThing argue that the plaintiffs fail to state claims upon which relief can be granted, that they lack standing to assert the claims at issue, and that their claims are barred by “the doctrines of estoppel, laches, unclean hands, waiver and/or acquiescence,” among other things.

Beyond that, the brands assert that the claims of absent class members are barred on an individual basis due to a lack of materiality of the plaintiffs’ allegations that the marketing messaging at play was “deceptive.” Specifically, the Boohoo brands argue that such claims are immaterial because most of their consumers simply purchase goods from Boohoo, Nasty Gal, and PrettyLittleThing because of the inexpensive nature of the products … “not because of [their] reference pricing” – i.e., their “40, 50, or 60% off” pricing.

“Purchasing behavior is complex,” Boohoo, Nasty Gal, and PrettyLittleThing each argue, “and the overwhelming majority of [their] customers bought items for many different reasons that had no connection to the reference pricing, and without any misunderstanding as to what the reference price means.” In reality, they contend that “most of [their] customers” shop on their sites “because of [the] competitive pricing,” not necessarily because of any reference pricing tactics.

The brands go on to argue that not only do the plaintiffs “fail to allege facts sufficient to entitle [them] to any award of such damages,” the conduct that they complain of is not actually “unlawful, unfair, fraudulent, deceptive, untrue, or misleading.” These arguments harken back to ones previously made by the defendants, including that the plaintiffs “do not allege that the defendants failed to ship the products, that the products [they] received were not as represented, or that [they] lost any money” in connection with their purchases.

The latter point is “not surprising,” according to the brands, “given the prices that the plaintiffs paid for the handful of products they purchased.”

In a previous filing, Boohoo argued that that despite claiming that they “fell victim to the deception” of the retailers’ various sale events, the plaintiffs do not allege any tangible harm. Khan, for instance, claims that he was duped by Boohoo’s “50% Off Everything” advertising, but “does not allege that he is out-of-pocket anything, e.g., that his $6 t- shirts were worth less than the rock-bottom price he paid for them.” As such, Boohoo and co. argued that the plaintiffs lack standing to bring their suits since “they do not plausibly allege that they suffered any damages, i.e., that the price they paid was more than the value received.”

And still yet, Boohoo, Nasty Gal, and PrettyLittleThing assert that “all or part of the claims” asserted by the plaintiffs are barred by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the free speech provision of the California Constitution, “which protect, among other things, [the] defendants’ right to promote and advertise the products at issue.” The statutes that the plaintiffs rely on, including California Business and Professions Code section 17501 – the statute upon which their false advertising claims are based on – “unconstitutionally regulate free speech.”

Los Angeles v. J.C. Penney

Such a free speech assertion is not unprecedented, as J.C. Penney, Sears, Kohl’s, and Macy’s argued – in a not dissimilar case – that Section 17501 violates the First Amendment and California’s liberty of speech clause, and is unconstitutionally vague. In that case, which was filed in 2017, the Los Angeles city attorney argued that the retailers ran afoul of the California state law by offering up their products at “reference prices” that purported to reflect former prices.

(Section 17500 states, “No price shall be advertised as a former price of any advertised thing, unless the alleged former price was the prevailing market price as above defined within three months next immediately preceding the publication of the advertisement or unless the date when the alleged former price did prevail is clearly, exactly and conspicuously stated in the advertisement.”)

However, instead of actually reflecting previously-used prices, J.C. Penney and co. “deliberately and artificially set the false reference price higher than its actual former sales price so that customers are deceived into believing that they are getting a bargain when purchasing products,” according to the city.

In a motion to dismiss, the defendant retailers argued that the statute restricts free speech rights and is unconstitutionally vague, and the trial court agreed, only to be overturned by the state appeals court in May 2019.

“By vacating the trial court’s grant of demurrer on grounds the statute was void for vagueness, the appellate panel’s decision reaffirms the validity of Section 17501,” Manatt’s Richard Lawson stated at the time. “It also puts retailers on notice that additional enforcement actions may be in their future.” At the same time, Holland & Hart’s Brent Johnson and Nathan Archibald noted that in light of the court’s decision, and the difference between the California state statute – which focuses on the “prevailing market price” – and the Federal Trade Commission’s – which centers on a retailer’s “own former price,” unless and until “a California court strikes down Section 17501 for violating the free speech rights of retailers, even a truthful price comparison is a violation if it does not meet the strictures of California’s pricing statute.”

*The cases are Farid Khan v. Boohoo, Haya Hilton v. PrettyLittleThing.com, and Olivia Lee v. NastyGal.com, 2:20-cv-03332 (C.D.Cal.),