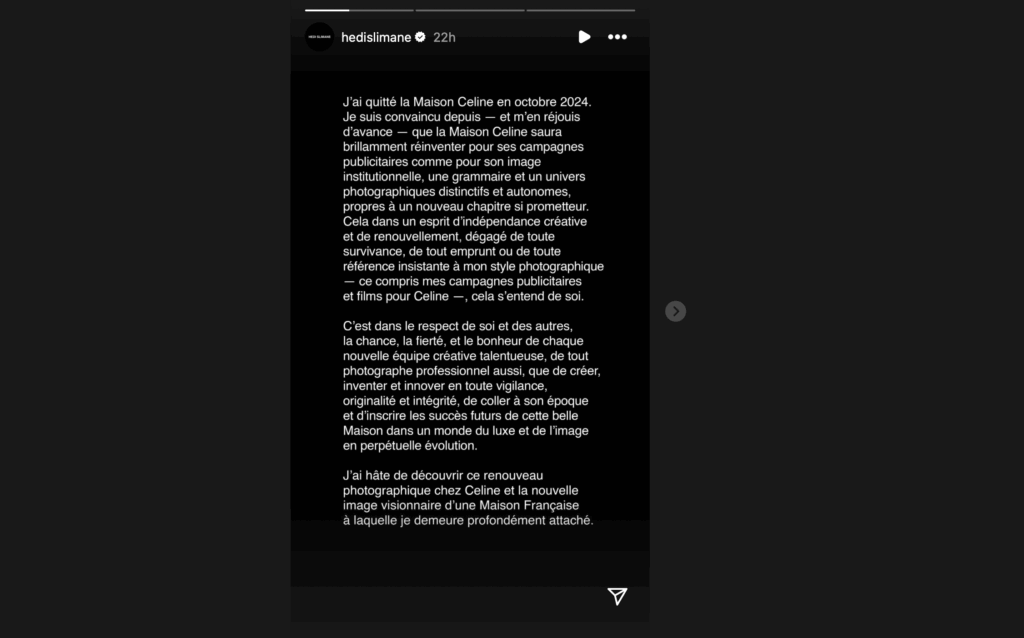

Hedi Slimane took to Instagram this weekend with a pointed note that is stirring chatter across the industry. In an Instagram story on Saturday, the cult-favored architect of skinny tailoring and the high-fashion rock-and-roll uniform revealed that he is “convinced – and rejoicing in advance – that Celine will brilliantly reinvent itself” with a fresh visual language and identity, one that is “distinctive and autonomous.” And Slimane did not stop there: He asserted that this reinvention must come “in a spirit of creative independence and renewal,” free of any reliance on, or reference to, the photographic universe he built at the house, including his campaigns and films.

The message is clear: Slimane, who is almost a year out from his position as the creative head at LVMH-owned Celine, is drawing a firm boundary around his authorship (and presumably, legal rights that he has in these creative assets), signaling that Celine’s next chapter should chart its own visual course rather than lean on the language that he made inseparable from the brand’s identity.

The (legal) background behind Slimane’s statement is maybe more interesting than the sentiment, itself. The designer, after all, maintains one of the most striking contractual arrangements when it comes to his work.

The (Legal) Backstory

In spring 2016, shortly after news broke that Slimane would leave Saint Laurent, the Kering-owned brand abruptly wiped its Instagram clean. Gone were the black-and-white images of skinny suits and grunge-inspired looks that Slimane had both designed and photographed, fueling speculation over whether the move signaled a new beginning for the brand or the result of a behind-the-scenes legal squabble.

The answer came quickly: Within weeks of his departure, Slimane filed two lawsuits against Kering, challenging the waiver of his non-compete clause and the calculation of his compensation. In a rare twist, Slimane demanded that the non-compete be enforced – and paid out. French courts agreed, awarding him more than $22 million in combined compensation and equity-related claims.

Yet, the more intriguing clash centered on Slimane’s photography. Unlike most creative directors, he had not assigned the rights to his campaign imagery to the house. While standard contracts ensure that advertising and design IP belongs to the brand, Slimane retained authorship. The Paris Court of Appeal sided with him, ruling that although he had been paid nearly €8 million to shoot the campaigns, YSL’s usage rights expired two years after his exit. By continuing to use the work more than 100 times without renewal, the brand was liable for infringement.

Slimane ultimately won about $700,000 in damages connection with Kering’s use of his imagery – far less than the $6 million he sought, but a rare and powerful affirmation that the imagery belonged to him, not the house. (The court also awarded Slimane upwards of $35 million in damages in connection with contract and equity aspects of his dispute with Kering.)

A Rare Setup … But More Than That

The decision sets Slimane apart from nearly all of his peers. Fashion houses routinely hold sweeping control over creative directors’ work – from design patent-protected handbags and shoes to the copyrights in ad campaign images. That Slimane could assert ownership over his photographs years later is a stark reminder of how unusual his arrangement was, and how carefully he appears to have negotiated his contract. That same leverage reportedly continued during his nearly seven-year term as creative director for Celine, with Slimane again said to have negotiated a deal to amass rights in various assets, including imagery and video campaigns.

But behind the obvious – and legally straightforward – message in his Instagram post (that the brand imagery and video campaigns, which are easily protected by law and assignable, are his) is a more nuanced issue. Regardless of the terms of Slimane’s employment contract and/or separation agreement with LVMH and specifically, which party holds which rights in which assets, the more compelling aspect centers on elements that are not actually protectable at all. Grunge-era apparel, skinny tailoring, black-and-white style photography, and rock-and-roll inspiration may be central to Slimane’s aesthetic (honed since his early days at Dior Homme) and thus, Celine’s identity during his time there. But these are largely aesthetic signatures that the law offers little – if any – protection for.

That tension – between what rights IP law and contracts can secure and what resides more squarely in a larger cultural moment or movement – is precisely where Slimane has long staked his claim. In other words, the power that Slimane has wielded throughout his career is less about the legal rights he holds than the consistency of a point of view that he brings to the table – one strong enough that audiences now instinctively associate that aesthetic with him. (This is true even if the building blocks of this aesthetic were drawn from broader cultural currents.)

And that is also what makes his Instagram reminder so potent: setting aside any legal ownership of campaigns, videos, archives, etc. the cultural ownership of the aesthetic, itself, something that exists squarely beyond the confines of the law, continues to orbit Slimane.