Brands are driven by core and often common aesthetics. In the direct-to-consumer space, for example, the Warby Parker model – which strategist Ana Andjelic has described as “a crisp, minimal aesthetic with a touch of quirk that carries through every design element, from mail order boxes to stores” – has been replicated repeatedly, particularly by other DTC players. Such a homogenization is hardly confined to the DTC space, with luxury brands busy adopting lookalike logos in recent years, prompting the so-called “blanding” movement, and others offering up their products and services on markedly similarly-designed websites.

Beyond the immediate visual elements of a company, Warby Parker founder Neil Blumenthal has noted in the past that a brand is more than its trademark-protected word marks and logos, it is “a point of view, and that point of view needs to be lived,” a notion that has lent itself nicely to the eyewear company’s buy-one, give-one approach to selling and donating eyewear (a la TOMS), in furtherance of a mission (and marketing model) that aims to go beyond purely selling stuff to helping others.

This giving or charitable element has also caught on among burgeoning young brands. As creative consultant Thierry Brunfaut asserted in his article, The Branding Vaccine, “On startups’ websites, mission statements ending with ‘… for a better world’ became the norm. Purposes and values pulled out of thin air for vacuous brands, no matter if the brand is manufacturing socks, selling car parts, or trading oil derivatives.” In their hallways, “We are bombarded with values and purpose texts plastered on the walls,” while “in the board room or at the founders’ table, common sense, candor, and sincerity have largely disappeared.”

It is difficult not to notice the mission-centric leanings of so many startups in the retail space. “Businesses like Warby Parker and Everlane were part of a new group of companies, with younger and less polished leaders, that claimed to lead with a set of values and the belief that they could sell directly to their customers,” Modern Retail’s Cale Guthrie Weissman recently wrote. “Glossier, for example, has an entire page dedicated to its brand values, which include being ‘inclusive,’ ‘curious,’ ‘courageous’ and ‘discerning,” while Everlane has built an entire business on the tenets of “radical transparency” and “ethical” sourcing.

In short: this particular breed of startup has “taken great pains to make their marketing sound broadly moral.”

Given the large-scale uniformity among brands both in terms of visual identity and mission-driven purpose, and in light of their dedication to staying within the bounds of that overarching aesthetic (look at their stores, websites, and Instagram accounts if you need proof), it should come as little surprise that even in moments of crisis, many of these companies look – and act – the same way.

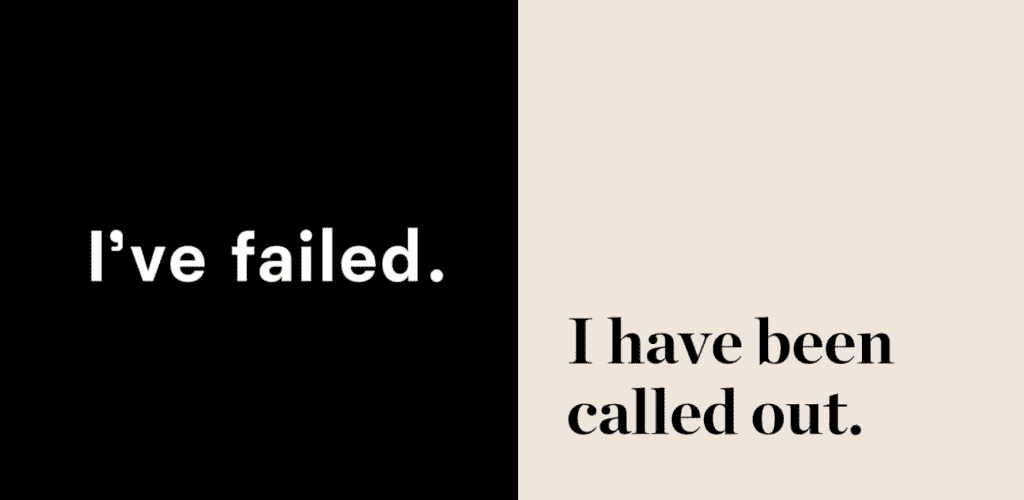

“Brand apologies have begun to look homogenous,” Weissman aptly asserts. For instance, on the heels of being called out for allegedly discriminating against employees of color, sustainable clothing brand Reformation posted an apology on Instagram with the words “I failed.” The typeset mirrors that of previous posts, enabling the company’s post to fit into the brand’s carefully-curated digital universe.

“Onlookers noticed other brands also posting apologies that were intentionally designed to look ‘on brand,’ which is to say that much of the public facing work, as of now, has been on the marketing side,” according to Weissman. As one Twitter user, writer Helen Donahue, asserted, “I’m losing it thinking about graphic designers being asked to design apologies but keep it ‘on brand.” Donahue also pointed to a similar apology posted by business coach Jenna Kutcher, which stated that she had been called out.

When Everlane was forced to speak out in response to claims that it had retaliated against employees for seeking to unionize, it issued a carefully designed series of Instagram posts, which – at first glance – appeared to mirror any of its other text-centric posts, such as those alerting followers about its plans to skip Black Friday or the recent post explaining why it is “going organic.” Eyewear brand Krewe, which is said to be in the midst of a standoff with upwards of a dozen employees in regards to its approach to valuing (or better yet, not valuing) Black culture, just might follow suit.

It is almost impossible not to wonder whether these utterly-Instagrammable apologies are merely the latest efforts by brands to not only save face (and save their bottom-lines during an already-difficult time) but also to attempt to bolster the often-explicitly “mission” oriented nature of their operations. After all, aside from disrupting the traditional retail model by cutting out the middleman and going all-in on social media content-as-advertising, this morals or ethics-driven approach is a large part of what initially helped to set these companies apart from other, more established market entities.

The popularity of Reformation and Everlane, for instance, was helped along because of their self-professed dedication to sustainability (and in Everlane’s case, transparency), particularly since market giants like Zara and H&M were coming under fire – and continue to come under fire – for their pioneering of cheap, disposable fashion, often made in sub-par workings conditions. These companies and their values-centric branding provided a cool alternative to that. As a result, such do-good elements have since become embedded in the identities of these brands and similarly-situated companies, which make them difficult to shed and also increasingly prove to be points of contention for consumers when they are not carried out consistently.

At the same time, broader expectations about how these companies conduct themselves have also entered into the mix given that they are marketing – and to some extent, profiting from – this larger message of morals, making allegations of racial discrimination and reported attempts to stand in the way of unionization efforts, for example, even more problematic.

With that in mind and considering the recurring need for these brands to make such apologetic statements (regardless of how heavily-branded they are), questions abound about the extent to which these companies’ core consumer-facing value statements (i.e., the ones that they have build their brands upon at a truly foundational level) are anything more than good intentions paired with effective, millennial-targeted marketing; marketing that went largely unchecked until now.

Instances like this will almost certainly prove telling, particularly given that consumers are paying attention, maybe now more than ever before.