Brooks is pushing back against the trademark and design patent infringement lawsuit waged against it in July by Puma, in which the German sportswear brand claims that Brooks is not only infringing its NITRO trademark by selling sneakers bearing that mark but goes further by adopting “every aspect” of a sneaker for which PUMA has a design patent in furtherance of what PUMA calls a larger “pattern of [Brooks of] copying [its] technology and disrespecting [its] intellectual property rights.” In the answer that it lodged with a federal court in Indiana on September 28, Brooks denies Puma’s infringement allegations and sets out a handful of counterclaims, seeking declarations from the court that it is not infringing Puma’s alleged trademark rights and its design patent, and angling to get Puma’s patent invalidated.

On the trademark front, Brooks aims to chip away at Puma’s infringement claim, arguing that “Puma asserts that its decision to name its line of nitro-infused midsole shoes ‘Nitro’ gives [it] the right to prevent Brooks from using the word ‘nitro’ to describe Brooks’ earlier-introduced, nitro-infused midsole shoes.” Puma “is wrong,” according to Brooks, which claims that “Puma has no rights to the word ‘nitro,’ which it uses in a descriptive manner, and it certainly has no rights to prevent Brooks from using ‘nitro’ to describe Brooks’ own nitro-infusion technology.”

Seattle-headquartered Brooks asserts that not only does Puma lack a trademark registration for “Nitro” (it filed trademark applications in December 2021), its use of “nitro” on its collection of nitro-infused midsole shoes is descriptive, and Puma “has not acquired any secondary meaning in the mark.”

Even if “Puma’s use of ‘Nitro’ was not descriptive (which it is),” Brooks argues that Puma – which began offering up its “Nitro” sneakers “in or around 2020, at least a year after Brooks first introduced nitro-infused midsoles” – “would have no priority and no enforceable rights in ‘nitro’ for running shoes or apparel, [as] numerous other running shoe companies, including Brooks, used the word “Nitro” for running shoes long before Puma.” Brooks claims that it first offered a shoe called the “Nitro” shoe in 1998, and since then, no shortage of other brands – from Nike and adidas to Saucony and Asics – have offered up running shoes under the Nitro name.

(Brooks also notes that the U.S. Trademark and Patent Office “has repeatedly rejected attempts [by other companies] to register ‘nitro’ as a trademark for nitro-infused products,” with examiners for the trademark office explaining that “nitro” is “a descriptive shorthand term for ‘nitrogen,’ that ‘nitro’ is not distinctive to the nitro-infused products of any one company, and that ‘nitro,’ therefore, cannot be registered as a trademark when used in connection with nitro-infused products.” The “same result holds true” for Puma and its nitro-infused shoes, Brooks contends.)

Beyond Puma lacking trademark rights in “nitro,” Brooks argues that it is not using the term as an indication of source of its sneakers, stating that “none of [its] nitro-infused shoes are named or labeled as ‘nitro’ or anything similar.” Instead, Brooks claims that it uses the term “nitro” exclusively “to describe the nitro-infused technology in its products.” This is significant, as a successful infringement claim requires “use” of a trademark – in a trademark capacity – by the allegedly infringing party.

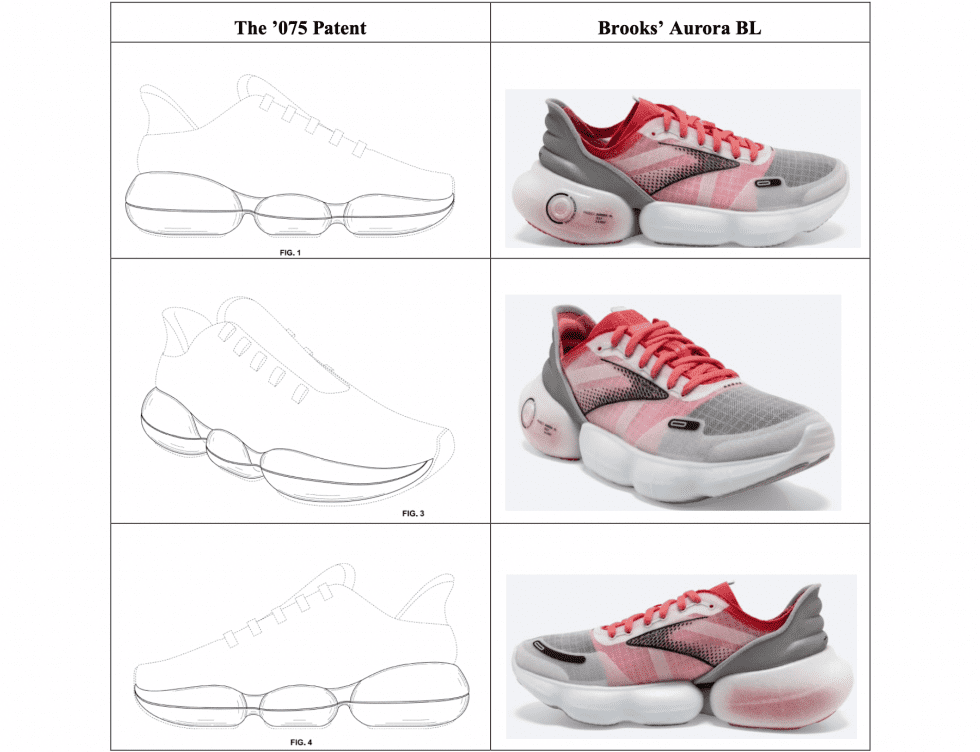

As for Puma’s design patent infringement claim, Brooks claims that Puma’s allegations – which center on its D897,075 patent, namely, “a single claim directed to the midsole of a shoe” – are “meritless,” as the D075 patent design and the design of its Aurora BL sneaker are “plainly dissimilar.” And the “numerous, immediately-apparent differences in design” between the patent design and the Aurora BL make it so that “an ordinary observer would not confuse the overall design of the Aurora BL with the overall design of [Puma’s] D075 patent,” according to Brooks.

While “no ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, would confuse the two designs” (i.e., the standard for gauging design patent infringement), Brooks asserts that there is an even more fundamental issue: Puma’s patent is invalid. “In addition to being primarily functional rather than ornamental,” Brooks argues that “the design in the D075 patent is not novel and is obvious over the prior art,” such as various Nike Air Max styles and Balenciaga’s hot-selling Triple S sneakers, among others. Brooks claims that “Puma omits examples of prior art soles that would further lead the ordinary observer to conclude that the differences between the design of the Aurora BL and the claimed design were significant, and that the designs were dissimilar.”

With the foregoing in mind, Brooks says that it is entitled to declaratory judgments, including a judgment that Puma has no rights in “Nitro” for use on footwear; a judgment that it is, thus, not infringing Puma’s alleged “Nitro” mark; and a judgment that it is not infringing Puma’s D075 patent because “in the eye of an ordinary observer … the design claimed by the patent and Brooks’ accused product are not ‘substantially the same’ such that ‘the resemblance is such as to deceive such an observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other.’” Brooks is also seeking a judgment as to the invalidity of Puma’s patent on the grounds that its fails to meet the statutory requirements for patentability.

And still yet, Brooks is also seeking an order dismissing the complaint with prejudice, along with a finding that this case is exceptional, and that reasonable attorney’s fees and costs should be awarded as a result.

Not merely an isolated instance, Brooks argues in its response that the Puma lawsuit is part of “a worldwide campaign on its rival’s part to bully Brooks into abandoning use of ‘nitro’ to describe its nitro-infused midsole technology.” Specifically, Brooks states that Puma has “brought emergency motions for injunctions against [it] … in multiple foreign countries … based on alleged licenses to ‘Nitro’ that Puma claims to have obtained from non-footwear companies.” Puma has “even gone so far as to try to freeze Brooks’ European bank accounts, purportedly in order to preserve the availability of money damages,” Brooks asserts, “even though Brooks is an established international company and a Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary, and Puma’s damages claim, by its own account, totaled only 150,000 Euros.”

“None of Puma’s aggressive tactics has succeeded,” Brooks claims, asserting that “no court in any country has granted an injunction against Brooks, and German courts have already twice rejected Puma’s request for an ex parte injunction on the basis that ‘nitro’ is descriptive of Brooks’ and Puma’s technology.” Against the background, Brooks contends that it “will not be intimidated by Puma’s efforts to enforce invalid intellectual property rights or to prevent [it] from accurately describing its innovative nitro-infused midsole technology,” which is why Brooks says that it is bringing its counterclaims.

Not limited to its answer and counterclaims, Brooks Sports also lodged a motion to transfer the venue of the Puma lawsuit out of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington on September 28, arguing that “there can be no dispute that venue is proper in W.D. Wash.” because, among other things, “Brooks is incorporated and headquartered there, and thus ‘resides’ in W.D. Wash,” and W.D. Wash. is “no less convenient for Puma than this District, since Puma is located in Massachusetts and does not allege a presence in this District.”

The case is PUMA SE, et al. v. Brooks Sports, Inc., 1:22-cv-01362 (S.D. Ind.).