Khloe Kardashian and her label Good American were handed a striking loss late last month, with a California state court shutting down the special motion that they filed in an attempt to get two of the claims lodged against them by dbleudazzled tossed out. In a decision dated December 28, Judge Elaine Lu of the California Superior Court in Los Angeles sided with celebrity-embraced fashion brand dbleudazzled, holding that statements made by the reality mega-star and Good American concerning their own lookalike bodysuits are exempt from the protections of the state’s anti-SLAPP statute.

Three months after dbleudazzled filed a $10 million fraud and deceit, common law trade dress infringement, misappropriation, and unfair competition complaint against Good American and Kardashian (the “defendants”) in May 2020, the 5-year old fashion brand and its famous founder responded with a special motion to strike dbleudazzled’s California Unfair Competition Law (“UCL”) claims on the basis that they fall within the bounds of the state’s anti-Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (“SLAPP”) statute, and thus, should be dismissed in order to protect the defendants’ “constitutionally protected speech.”

Setting the stage for its anti-SLAPP claims, Kardashian and Good American asserted in their August 2020 motion that dbleudazzled’s UCL claims “present a classic case of trying to suppress a victim’s public response to a series of widely publicized fabrications, [which is] precisely the kind of protected speech the anti-SLAPP laws were enacted to safeguard.” Enacted in 1992, California’s anti-SLAPP statute protects parties from lawsuits brought to “chill the valid exercise of constitutional rights of free speech,” and provides parties with the ability to file a special motion to strike a complaint or parts of a complaint when a case has been filed “primarily to discourage speech about issues of public significance,” which is precisely what the defendants argued is going on in the case at hand.

Specifically, Kardashian and Good American claimed in their motion that dbleudazzled “relies on three of [their] statements … as the basis for [its UCL] claims,” with dbleudazzled arguing that the defendants’ claims – including that they did not copy their lookalike bodysuits – are false and misleading, and therefore, “constitute a fraudulent business practice” in violation of the sweeping California state law, which prohibits “unlawful, unfair or fraudulent business acts or practices.”

In terms of the statements, themselves, the first is an official statement from Good American – which asserted in a June 2017 article published by Cosmo in connection with dbleudazzled’s public claims that Kardashian and her brand copied her distinctive bodysuits – that “under no circumstances did Good American or Khloe Kardashian infringe another brand’s intellectual property.” The second “statement” comes in the form of June 2017 Instagram posts of images of Cher, Diana Ross and Britney Spears in crystal embedded tops along with the language, “Important to know your fashion history #nofrauds,” “Vintage Diana Ross. Showgirl vibes. #inspo” and “Britney in Toxic #inspo,” all of which were in reference to allegations that the designs were inspired by/infringed dbleudazzled’s trade dress in embellished bodysuits.

Finally, in the third statement, Kardashian suggested in a June 2017 Instagram post, in which she announced the launch of the Good American bodysuit collection, “that she came up with the designs for [her allegedly infringing] bodysuit over the course of almost a year, when in reality,” dbleudazzled claims, “she spent several months ordering [dbleudazzled’s] bodysuits and copying those designs.”

Following back and forth filings between the two parties this fall, the court issued its decision on December 28, shooting down the defendants’ quest to get dbleudazzled’s UCL claims dismissed. Considering the defendants’ anti-SLAPP motion, the court stated that it entails a two-step process, with the first prong calling on the court to examine “the nature of the conduct that underlies the plaintiff’s allegations to determine whether the conduct is protected by [the anti-SLAPP statute].” If the first part is met, the second prong requires an assessment of the merits of the plaintiff’s claim.

Protected Activity?

Addressing the first prong, the court stated that it requires the defendants to show that the plaintiff’s claims arise from protected free-speech activity, or in the case at hand, the speech in question – i.e., the three statements made by Good American/Kardashian – was made “in furtherance of a person’s right of petition or free speech … in connection with a public issue.” More specifically, the speech must fall within one of the four scenarios set out in – and protected by – the anti-SLAPP statute, with the relevant one here being “any written or oral statement … made in … a public forum in connection with an issue of public interest.”

In this case, the court found that the three Good American/Kardashian statements “were each made in a public forum,” whether that be in a Cosmo magazine article or on a social media platform. More than that, the statements “concern a matter of public interest,” as “Kardashian is in the public eye,” and “the context of the [Good American, dbluedazzled] controversy indicates that the matter is of public interest,” particularly given that Kardashian has “been accused on numerous occasions of copying designs from smaller independent fashion brands.”

The public nature/interest of the statements boded well for Kardashian and Good American’s anti-SLAPP allegations. However, at the same time, Kardashian and her brand hit a roadblock, as the anti-SLAPP statute and California case law require that in order for a claim to be protected by the statute, it must arise from protected activity. That presented a complication here, according to the court, as dbleudazzled’s UCL claims are based on two categories of wrongful conduct: Khloe and Good American’s “misleading statements (which the defendants assert constitute protected activity), and [their] infringement of [dbleudazzled’s] trade dress, which [they] do not assert constitutes protected activity.”

Because dbleudazzled’s specific UCL claims (as distinct from its fraud and deceit, common law trade dress infringement, and misappropriation claims) are based at least in part on the unprotected activity – i.e., the defendants’ infringement of its trade dress, the court ultimately held that “the defendants’ special motion to strike the UCL claims in their entirety is denied.”

Commercial Speech Exemption

Before writing off the first prong entirely and handing dbleudazzled a win, though, the court asserted that in line with the California Supreme Court’s holding in Baral v. Schnitt, it must address “whether each of the allegations concerning the protected activity of false or misleading statements must be stricken pursuant to the defendants’ motion.” As such, the court addressed the “commercial speech exemption,” an exception for “certain expressive actions,” i.e., an action in which “the speaker must be (1) a personal primarily engaged in the business of selling or leasing goods or services, (2) making representations of fact about that person’s or a business competitor’s business operations, goods or services, (3) to an actual or potential buyer or customer, or a person likely to repeat the statement to or otherwise influence an actual or potential buyer or customer with (4) the purpose of … promoting or securing sales.”

In short, the court stated that whether the statute subsection exempts the speech at play “depends not only on the content of that speech but also the identity of the speaker, the intended audience, and the purpose of the statement.”

All of these factors were met, according to the court, as the defendants are in the business of selling goods via the Good American label; the statements at issue are representations about that business – including, “whether [or not] the defendants copied the plaintiff’s designs or infringed on another brand’s intellectual property;” the statements were made to or likely to influence actual or potential buyers given that two were made on Instagram, “which the defendants have stated is a primary method they use to engage with their fans,” and the other was made in an interview with Cosmo.

Finally, the court stated that for the fourth factor, an advertisement that is “primarily intended to reach consumers and to influence them to buy the speaker’s products is not exempt from the category of commercial speech because the speaker also has a secondary purpose to influencer [others].” Here, the court says that “the timing of the three sets of statement” – all made within a matter of weeks of the launch of the Good American bodysuits – “coupled with how” they were made – on social media and in a fashion magazine – shows that they were made to promote the brand and its wares. As such, the court found that all three statements fall under the “commercial exception” of the anti-SLAPP statute, and as a result, dbleudazzled’s UCL claims should not be dismissed in connection with the defendants’ anti-SLAPP motion.

Given that the first prong fails, dbleudazzled “asserts that the court need not proceed to the second prong of the analysis of the anti-SLAPP motion” – and asses the merit of the plaintiff’s claim – because each of the statements at issue falls within the commercial speech exemption of the anti-SLAPP statute, and the court agreed.

“Minimal Merit”

Nonetheless, the court stated that even if it were to find that any of three statements was not exempt, Good American/Kardashian’s motion further fails, as dbleudazzled met the “minimal merit” standard – or in other words, Destiney Bleu Lewis’ 8-year old brand established that its case has at least some merit.

Among the points set out by dbleudazzled in furtherance of its claims against the defendants, the court noted that “from November 2016 through May 2017, Defendant Kardashian contacted [dbleudazzled] to order at least 16 made-to-measure garments under the false pretense that these garments” – which have “a distinct [and non-functional] look and feel with careful placement of crystal rhinestones on intimate garments made of form-fitting materials … with a sheer or semi-opaque look” – were for “Kardashian’s personal use.” At the same time, “Kardashian also borrowed a number of hand-sewn, crystallized garments from [dbleudazzled], including a distinctive black and nude bodysuit,” without ever disclosing that she “intended to create a line of bodysuits with similar crystal burst patterns.”

All the while, dbleudazzled also asserted that “Kardashian’s sisters and close business associates, Kendall and Kylie Jenner, had requested to borrow or purchase at least [a] black and nude bodysuit with the same crystal burst pattern around the bust” via the merchandise coordinator for their KENDALL + KYLIE brand.

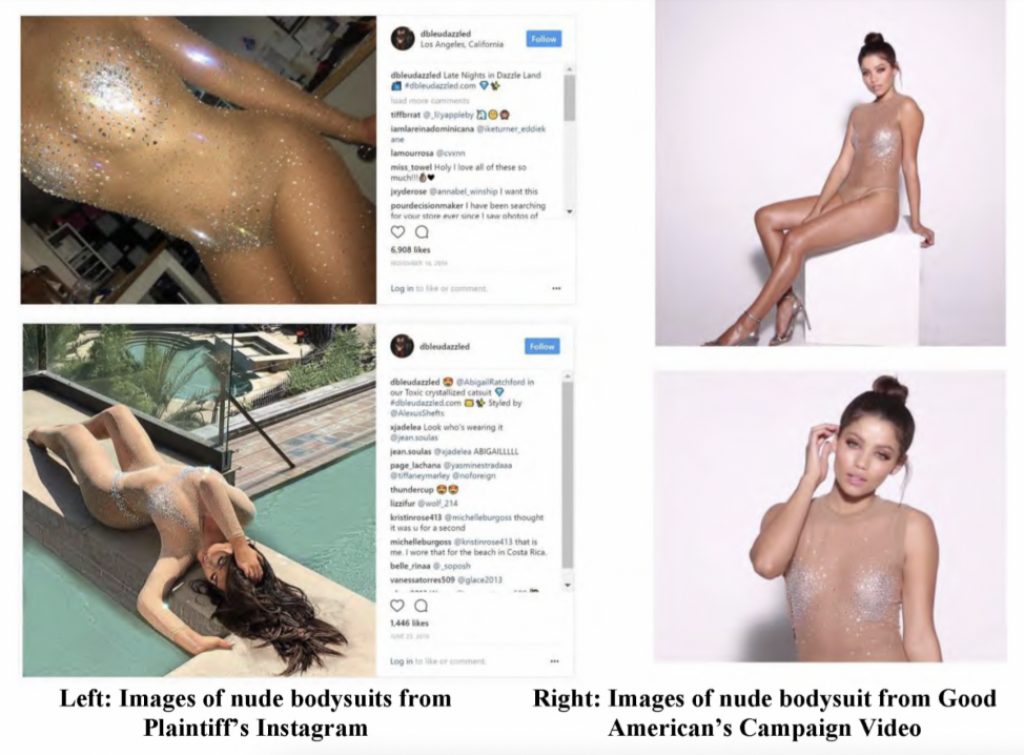

Fast forward to June 1, 2017, and Kardashian/Good American “released a campaign video on social media containing footage of [their] ‘nude’ and black bodysuit to be released in conjunction with their denim apparel. Both of these designs used a ‘crystal burst around the bust,’ copying the plaintiff’s design and making it confusingly similar to the plaintiff’s bodysuit design.” The similarity was not lost on dbleudazzled’s customers and other members of the public, who “quickly realized that the defendants had copied the design and overall look and feel of [dbleudazzled’s] distinctive bodysuits and made numerous media reports and social media commentary pointing out the copying.”

While Kardashian has since denied in a declaration in the case that she ever received bodysuits from dbleudazzled, and instead, only received “catsuits,” the court asserted that “the lack of evidence placing [dbleudazzled’s] infringed bodysuits in Kardashian’s hands does not refute [dbleudazzled’s] circumstantial evidence that Kardashian infringed [its] bodysuits.” Instead, the court held that dbleudazzled’s “evidence demonstrated that Kardashian had access not only to [the brand’s] actual clothing items but also to [dbleudazzled’s] online look book, at least including the brand’s website and Instagram pages,” which showcased its embellished designs.

With that in mind, the court determined that dbleudazzled presented sufficient evidence to “demonstrate minimal merit to its claim that each of the statements [at issue] was false and misleading insofar as it suggested that the defendants did not copy the plaintiff’s design.” As such, the court denied Good American/Kardashian’s anti-SLAPP motion, thereby, enabling dbleudazzled’s UCL claims to remain in effect, and leaving the case to proceed.

The immediate outcome is the latest in a long string of decisions centering on California’s anti-SLAPP statute, which is “the strongest and most frequently litigated statutes of its kind in the U.S.” Judge Lu’s decision follows from a series of cases in which “California courts have more narrowly construed the anti-SLAPP statute, [thereby] suggesting continued interest in the courts in defining the contours of the law,” according to Morrison & Foerster LLP’s Derek Foran and Michael Komorowsk. One of those cases? The California Supreme Court’s 2016 unanimous decision in Baral v. Schnitt, in which the Supreme Court reversed an appellate court’s decision, and held that where a mixed cause of action arises from both protected and unprotected activity, as was the case here, an anti-SLAPP motion can be brought to attack those parts of the claim that arise from protected activity.

In doing so, the court “ensured that plaintiffs cannot simply game their complaint and avoid an anti-SLAPP motion by artfully combining alleged protected and unprotected conduct by a defendant,” per Davis Wright Tremaine’s Thomas Burke, while also providing guidance to California’s trial and appellate courts, which had lacked clear guidance on how to handle such “mixed” claim situations for roughly a decade.

*The case is dbleudazzled, LLC v. Khloe Kardashian and Good American, LLC, 20STCV20510 (Cal.Sup.).