A court in the European Union has refused to overturn an appeal board’s decision that a sustainability-centric slogan does not function as a trademark. On the heels of the European Union Intellectual Property Office (“EUIPO”) rejecting Groschopp AG’s application for registration for “Sustainability through Quality” and the Board of Appeal dismissing its appeal on the basis that the relevant public would view the mark as an advertising slogan (and not as an indicator of source), the EU General Court affirmed that the electrical drive tech. company’s slogan – when used in connection with engines, electrical devices, paper products/packaging, and IT/maintenance services – is likely to be perceived by consumers as a promotional phrase rather than as an indication of commercial origin.

Siding with the trademark office, the General Court stated (as first reported by IPKat) that while certain slogans – such as those that make use of “humor or unusual alliteration” – may be deemed distinctive enough to indicate source, that is not the case here. Instead, the court held that the applied-for mark consists of a “promotional and laudatory message that underlines the positive aspects of the goods and services concerned, namely that they are sustainable,” and that consumers “can expect superior quality and durability from these products and services, which would result in [them having a limited] impact on the environment.” At the same time, the mark “would also express a general and abstract corporate philosophy,” the court stated, as opposed to an indication of its source.

In what might prove telling for other companies looking to adopt – and attempt to register – green and/or ESG-centric trademarks, the court noted that “the words ‘sustainability’ and ‘quality’ and the ideas that they convey are already commonplace in the field of advertising.” As a result, they “confer advertising character on the applied-for mark,” particularly in light of the fact that “the public’s interest in sustainability in production and consumption has increased sharply in recent years.”

The court distinguished the mark at hand from the one at the center of the Audi v. OHIM case, in which the Court of Justice for the European Union held that the slogan “Vorsprung durch Technik” (advantage through technology) constitutes a protectable trademark because it had been used for many years by Audi to promote the sale of its cars, and thus, is capable of indicating source in the minds of consumers. Moreover, that mark (as distinct from “Sustainability through Quality”) could have several meanings, could constitute a play on words and/or could be perceived as fanciful, surprising, and unexpected, according to the court, which led to a determination that it was distinctive.

With the foregoing in mind, the General Court held that Groschopp’s “plea must be dismissed as unfounded, and the action must be dismissed in its entirety.”

THE BIGGER PICTURE: Not limited to the EUIPO, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and other trademark offices are seeing a rise in applications for sustainability/ESG-focused marks. (We first dove into this trend here and have since followed up here.) As of the date of publication, the USPTO lists almost 2,500 applications and/or registrations containing the word “sustainable,” nearly 35,000 that make use of the word “green,” and 13,500 that contain “eco.” Recent filings include those for marks like “Simply Sustainable” for use on cheese, “Sustainable Suncare” for body lotions and retail store services featuring skin sun-care lines, and “Sustainable Luxury” for linens.

A notable number of applications for registration for sustainability-focused marks have faced pushback on the basis that the marks are merely descriptive or generic. One example: Captalys Companhia de Crédito received an Office action from the USPTO in December, in which an examining attorney asserts that when used in connection with “financial analysis; financial consultancy, financial report related to economic-financial advice,” etc. the “Sustainable Credit” trademark “merely describes a feature or characteristic of applicant’s services.” An application for “Sustainable Compliance” for use in connection with “consultancy services namely, business advice on how to develop and manage sustainable compliance solutions” is facing similar pushback.

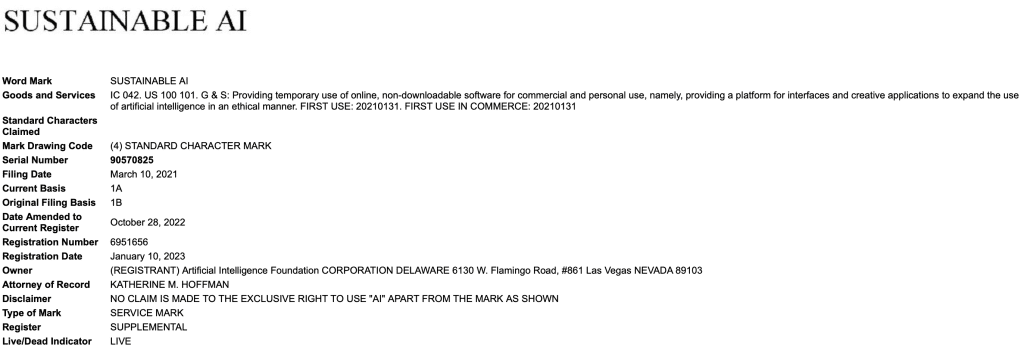

Meanwhile, after facing an initial refusal on mere descriptiveness grounds, “Sustainable AI” has been registered for “providing temporary use of online, non-downloadable software for commercial and personal use, namely, providing a platform for interfaces and creative applications to expand the use of artificial intelligence in an ethical manner,” as has SUSTAINABILITY-AS-A-SERVICE for use in connection with “downloadable and recorded application software for calculating environmental impact, offsets, and ESG investments, as well as for tokenization,” among other similar services.

Looking beyond the registrability (or lack of registrability) of these marks … Companies also need to consider the risk of false advertising – and allegations of greenwashing – in connection with the use of such marks if they misstate/overstate a company’s efforts and achievementsin the realm of sustainability/ESG. The USPTO, for instance, is authorized to regulate “green” trademarks under Section 2(a) of the Lanham Act, which broadly bars false and deceptive marks (i.e., those that are “misdescriptive of the character, quality, function, composition or use of the goods/services” and likely to mislead consumers).

At the same time, Perkins Coie’s Grace Han Stanton and Colleen Ganin previously noted that many brands are “leveraging trademarks to communicate social and environmental commitments.” Not without risk, they state that “rising market pressures have led to increased [regulatory] scrutiny for greenwashing,” which could very well extend to the use of green trademarks. The Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”), for example, has “warned against using broad environmental terms for marketing purposes, such as ‘eco-friendly’ or ‘green,’ without qualification because they convey multiple advertising claims, and it is unlikely marketers can substantiate all such claims.”

The FTC has since commenced a review of the Guides for the Use of Environmental Marketing Claims, known as the “Green Guides,” and called for public comment on “the continuing need for the guides, their economic impact, their effect on the accuracy of various environmental claims, and their interaction with other environmental marketing regulations.” The regulator is also seeking “information on consumer perception evidence of environmental claims, including those not in the guides currently,” indicating its increased attention (and the potential for future action) in this arena.

Simultaneously, the European Union maintains restrictions on misleading advertising and other unfair practices, which “apply to all business-to-consumer commercial practices, including those involving environmental claims,” per emlex’s Massimo Maggiore. In this vein, the EU Commission has also advised companies to avoid use of “vague or general terms, such as ‘green,’ ‘environmentally friendly,’ ‘eco-friendly,’ ‘harmless,’ ‘natural,’ or ‘sustainable’” – in connection with trademarks and/or marketing efforts more broadly – “as they are potentially misleading for consumers.”