What makes a brand a brand? That is the interesting – albeit complicated – question that Bernstein’s Bruno Monteyne and Luca Solca set out to answer in a recent client note. In doing so, the analysts consider a handful of other questions, namely, “What differentiates brands from commodities? Why do [brands] make so much money, and what determines how much money they can make?,” and come up with the following assertion: “a brand is a license to tax our emotions and dreams.”

Delving into the definition of a “brand” in a more concrete manner, Monteyne and Solca point to the “big gap between a marketer’s definition of what a brand is and what a brand, instead, appears to be in the … minds of consumers.” On one hand, they say that “marketers have a more factual assessment of brands: specific products and formulations, advertising campaigns over the years, design and logo choices and evolution, ‘story-telling,’ testimonials and representatives, and so on.”

However, this interpretation – which “gives the impression that a brand is something tangible” – “completely misses the point of what a brand really is and why it is valuable,” Monteyne and Solca argue. In contrast to a tangible asset, a brand is “intangible,” and thus, a more appropriate way to define a brand is as “the cumulated set of images, sounds, people, places, etc., and the emotional connections attached to them in the minds of each individual.”

This definition fits neatly within the realm of what is generally accepted by the legal field since intellectual property – or more specifically, trademarks (i.e., the protections that go to the heart of branding) – is inherently intangible in nature. More than that, this intangibility-centric definition makes sense from a legal standpoint given the critical importance that goodwill – or the recognition/reputation of a given trademark (or marks) among consumers and the extra earning power that such reputation generates – plays in connection with the role/value of trademarks.

Brands vs. Branding

Monteyne and Solca go on to distinguish the proper definition of a brand from the ones set out by various dictionaries. The “only point” that the dictionary definitions get across when it comes to a brand “is the ‘marking’ of [an] item with a distinctive mark/label and the way it helps to distinguish or ‘differentiate’ one manufacturer’s product from that of another.” The analysts assert that “imprinting a branding iron on a cattle’s bum may differentiate my cow from yours, but it doesn’t make it a brand.”

Doubling down on the cow analogy, they assert that physicalbranding may “differentiate” one cow from another by way of a “sign/symbol” (i.e., a trademark), but that “does not help [the cattle farmer] set the price of his cow. He still has to go to the cattle market where his cow will be traded as a commodity, as any other cow.” In other words, a critical intangible element is still missing from the equation to transform that source-identifying item (a cow, a handbag, a car, etc.) from a commodity to the offering of a “brand.”

As such, in addition to discerning that a brand is defined by a combination of intangible assets, Monteyne and Solca note that price – and price setting – plays a role.

As distinct from a commodity, which is priced by way of “a market clearing mechanism: supply and demand curves, marginal extraction costs, to settle on the right price,” brands have the unique “ability to price [their] products” (i.e., they have “a license to charge”), which the analysts say is an important component of being a “brand.” At the same time, “the differentiation of their products (the marking, the different product features) allow brand manufacturer[s] to set [their] prices,” per Monteyne and Solca, who also note that “the brand manufacturer has sufficient control … over the selling process [in order] to set its own price.”

Brand Equity & Premium Pricing

Also on the pricing front, Monteyne and Solca point to price-elasticity as a relevant consideration in their quest to define brands (and their offerings) and differentiate them from commodities. While price-elasticity – or how a change in a product’s price affects demand for that product – is not the defining concept of a brand, it is noteworthy, nonetheless, as it serves to indicate “the strength of all emotional connections a consumer has to a product,” and thus, a “brand.’”

Such emotional connections – or consumer perception of a company, more generally – are significant, as they are an integral characteristic of a brand, according to Monteyne and Solca. At the heart of both premium pricing power and low price-elasticity is an “emotional connection” between a brand and a consumer that negates the usual trend of consumer demand going down as price goes up. (“Positive elasticities are sometimes reported for luxury products that sell at very high prices,” according to the Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services).

Moreover, these very connections are a driving force in the brand equity metric, which is gauged by the “value premium that a company generates from a product with a recognizable name when compared to a generic equivalent.”

The flow of these elements is essentially this: Positive Consumer Perception/Emotion > Positive Brand Equity > Premium Pricing Power/Low Price Elasticity

Innovation & Emotional Connection

As for what motivates such an emotional connection, Bernstein points to a handful of important things – from the invention of new product categories to innovation on an aesthetic front.

“Luxury brands have been very clever to invent new product categories and integrate them into the same consumer relevance framework,” according to Monteyne and Solca. “Handbags, for example, look like a relatively recent category: Louis Vuitton reinvented itself in handbags, after trunks became irrelevant. (The same can be said of Hermès’ introduction of handbags and other leather goods to supplement its foundational equestrian offerings). Even more recently, luxury brands have expanded into new product categories previously outside an orthodox product driven definition of what luxury goods are. The fact that (mentally sane) younger consumers today are willing to spend $1,000 or more for a t-shirt or a pair of sneakers is the ultimate demonstration of what we are trying to explain here, and a feat of marketing excellence by luxury mega-brands, such as Gucci or Louis Vuitton.”

At the same time, they state that “innovation is very important in luxury goods too, contrary to what a superficial understanding of luxury goods brands would suggest. Some observers wrongly assume that luxury is all about heritage and tradition. If this was true, how museums would be chockablock with luxury brands – and they are not.”

“For starters, luxury goods brands need to aesthetically innovate their products: as much as people could love a blockbuster iconic product of brand X, the moment that all of the target consumers have bought one, two, three … they will probably be satiated and have less of a reason to part with their money and buy the nth one.”

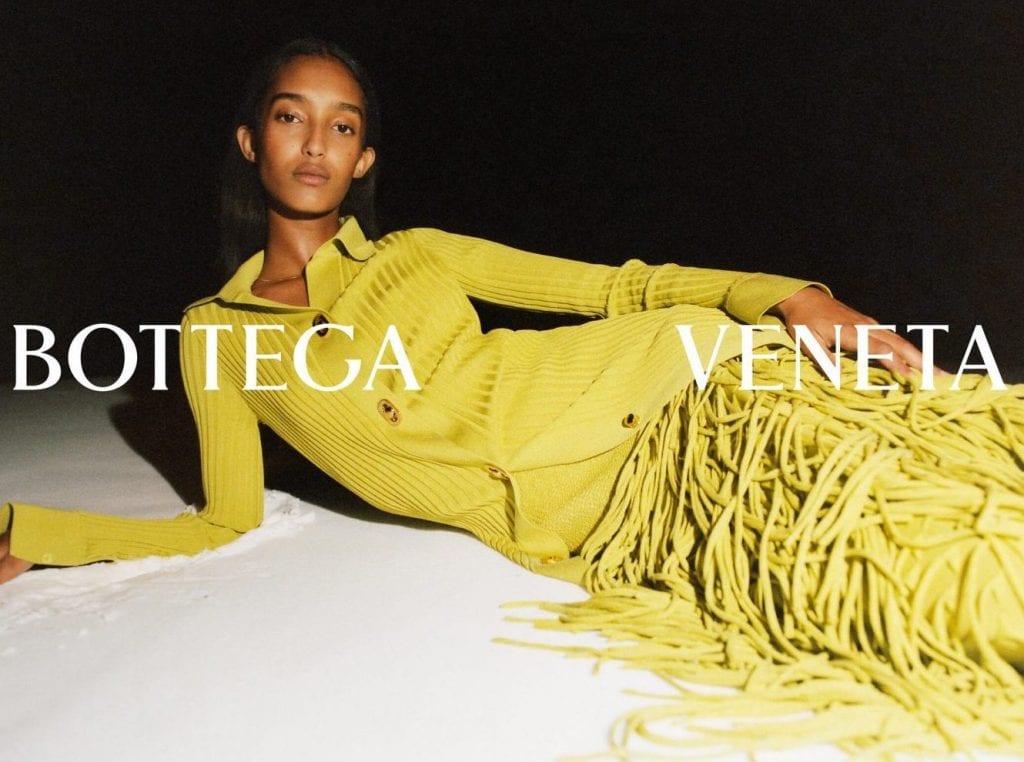

While Monteyne and Solca assert that “consumable luxury goods products (e.g. shoes) may get away for a longer amount of time with little variations,” hence, the enduring appeal of a brand’s staple handbag or “it” sneaker, “eventually [a] lack of aesthetic innovation will bore consumers and cause them to move elsewhere.” A good example of this, they say, is Bottega Veneta and its “intrecciato” weave-bearing handbags. Those products “drove growth for more than decade … until consumers had enough.” At that point, “Daniel Lee had to come in and replace Thomas Meier [as creative director], and invent a new breed of ‘intrecciato.’” In doing so, “BV is currently booming on the back of it.”

Coming full circle from their initial inquiry about how to define a brand, and in light of the interrelated nature of branding, consumer perception/demand, and pricing power (and elasticity), it is not surprising that Bottega Veneta’s reinterpretation of its “intrecciato” weave pattern – which is a registered trademark that was determined (as a result of thousands of pages of evidence and successful lawyering) to not merely be aesthetically functional and merely ornamental, but instead, to serve as an indicator of the BV brand in the minds of consumers – has driven demand and more broadly, increased brand power.

After all, as Monteyne and Solca state, “a core skill” when it comes to building and sustaining a brand – and thus, its power to employ premium pricing – is “to develop lots of incremental innovations and drive great marketing/branding behind that to build strong consumer engagement.”

At the same time, they note that in accordance with that same aim, “luxury goods brands” – no matter how they are defined – “are wise to integrate relevant values in the present Zeitgeist. These values, in fact, define the debate in our societies and are most likely going to be used by consumers as elements to define and support their [own] identities,” and thereby, inform their emotional connections with brands.