The developer behind an generative AI-powered app that enables users to “swap” faces with “well-known individuals and fictional characters” is looking to escape a proposed class action lawsuit that is being waged against it in a California federal court. According to the motion to dismiss that it filed on May 31, NeoCortext, Inc., the company behind Reface, claims that the suit that Kyland Young lodged against it in April should be tossed out on the basis that the reality TV personality not only fails to adequately plead a right of publicity claim, but even if he could, that claim is preempted by the Copyright Act and barred by the First Amendment.

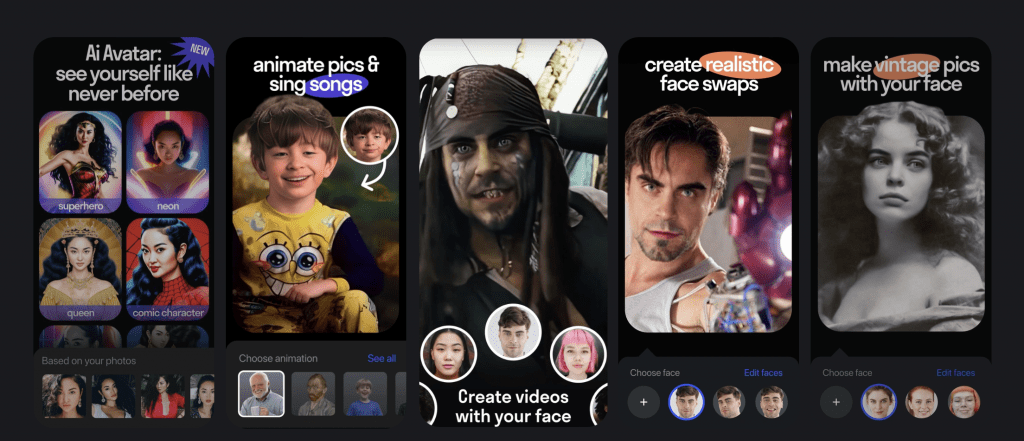

For some background: Young filed suit against NeoCortext, accusing the company behind the deepfake app of running afoul of California’s right of publicity law by enabling users to swap faces with famous figures – albeit without ever receiving authorization from those well-known individuals to use their likenesses. In his complaint, Young asserts that NeoCortext has “commercially exploit[ed] his and thousands of other actors, musicians, athletes, celebrities, and other well-known individuals’ names, voices, photographs, or likenesses to sell paid subscriptions to its smartphone application, Reface, without their permission,” thereby, giving rise to a single cause of action under the California Right of Publicity Statute (Cal. Civ. Code § 3344).

Fast forward to May 31 and NeoCortext is angling to get Young’s complaint dismissed on three key grounds …

Preemption – The Reface developer claims that Young has brought “a copyright infringement action masquerading as a right of publicity case” in an attempt to avoid the fact that “as one of many performers in [the] shows [in which he appears], Young almost certainly does not own the copyrights in the shows or photo stills from them,” the latter of which NeoCortext uses to enable those who use its app to “swap” faces and create “deepfake” imagery. (The core of Young’s right of publicity claim is that it “used photographs and videos of him from the CBS television program, Big Brother, in the free version of its Reface app,” NeoCortext claims,) “Faced with that inconvenient fact, [Young] instead claims [that NeoCortext] has used his likeness without his consent.”

The problem, per NeoCortext is that “where a right of publicity claim is based entirely on display, reproduction, or modification of a copyrighted work, like an episode of a TV show, the Copyright Act preempts the claim.” In furtherance of this argument, NeoCortext asserts that Young’s right of publicity claim centers on “rights that are equivalent to those protected by copyright law,” as Young “does not identify any use of his name, voice, photograph, or likeness independent of [its] use of the copyrighted photos or videos in which [he] is depicted.” Instead, he claims that NeoCortext violated his right of publicity by “displaying photos he appears [in] … in its online database” and “allowing end users to ‘generate a new watermarked image or video where the individual depicted in the catalogue has his or her face swapped’ with the face that was uploaded by the free user.”

As such, Young’s claim “presumes that Reface displays an expressive work – his photo or clips from Big Brother – and allows users to create and distribute derivative works from that work without his permission, both of which are exclusive rights under the copyright law.”

First Amendment – “Even if copyright did not preempt [Young’s] claim, the First Amendment bars it,” NeoCortext maintains, asserting that by way of his right of publicity claim, Young is “seek[ing] to quash the creative efforts of Reface users.” However, “because the uses of likenesses were purely to enable users to create their own unique, sometimes humorous and absurd expressions, the First Amendment protects the use.” NeoCortext claims that the language in Young’s complaint “acknowledges” the “transformative purpose” of the Reface app, “alleging that the app ‘uses a [generative] AI algorithm to allow users to swap faces with actors, musicians, athletes, celebrities, and/or other well-known individuals.” And since “the very purpose of Reface is to transform a photo or video in which [Young’s] (or others) image appears into a new work in which [his] face does not appear,” NeoCortext asserts that its “display of the original work is a necessary pre-cursor to this transformative process.”

Failure to Plead a Prima Facie Claim – Finally, NeoCortext asserts that Young falls short of pleading a prima facie right of publicity claim under California law, which requires a plaitniff to allege that the defendant “knowingly uses [his] name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness” for advertising purposes.” Specifically, NeoCortext argues that Young “does not allege that [it] knowingly used [his] name, photographs, and likeness, or that his name was even used in the first instance … nor does [he] sufficiently allege that its use of a watermark [on images created by the free version of the Reface app] constitutes advertising.”

On the knowledge front, NeoCotrext asserts that “nothing in the complaint indicates that it knew that photos and GIFs containing [Young’s] face were included in the database,” which consists of a “library of movie and show clips and images from online sources, such as mybestgif.com, tenor.com, Google Video, and Bing Video.” In the same vein, Young also fails to sufficiently plead that it uses his name in the Reface app, per NeoCortext, which states that the complaint “does not allege that users can search for [Young] by name, or whether video clips in which he appears are returned by a search for ‘Big Brother.’” And even if users could search for him by name, Young’s complaint “fails to allege that the search is of data maintained by [NeoCortext] instead of the third party sources of photos and video clips like Tenor and Google video.”

With the foregoing in mind, NeoCortext requests that the court grant its motion to dismiss Young’s complaint.

And an anti-SLAPP motion to strike … Not finished there, though, NeoCortext has also lodged a motion to strike Young’s right of publicity claim under California’s anti-SLAPP statute on the basis that: (1) the display of images of celebrities and other public figures in Reface are statements made in a public forum in connection with issues of public interest; (2) Young cannot demonstrate a probability of prevailing on his right of publicity claim (for the reasons set out in NeoCortext’s motion to dismiss); and (3) Young fails to plead a prima facie violation of his right of publicity.

THE BIGGER PICTURE: Young’s lawsuit is one of the latest to center on the products of generative AI outputs – joining cases like the ones that have been lodged against Stability AI and co. In light of the rush by companies to adopt AI, Young’s case “may foretell the emergence of a new breed of class action litigation brought about by artificial intelligence,” Covington & Burling’s Zach Glasser wrote in a recent note, stating that “intellectual property class actions are traditionally relatively rare, but generative AI makes it possible to create a large number of potentially infringing – but not identical – new works with one technology.”

When a single technology is involved, he asserts that “plaintiffs like Young may allege that there are enough common questions to make a class action appropriate,” while “defense lawyers may come to rely on core intellectual property doctrines and defenses – e.g., substantial similarity, fair use, and the First Amendment – in opposing class certification in ways they have not before.”

More broadly, other name, image or likeness (“NIL”) issues will almost certainly come about as a result of the rise of generative AI. The Reface app appears to consciously use celebrity images in order to enable users to swap their faces with such famed figures. However, given that the models that drive generative AI outputs are trained on sizable quantities of data from the web (including images in many cases), there is a chance that this will lead to “the possibility that some user prompts may cause the output to include the NIL of a celebrity,” according to Sheppard Mullin’s James Gatto, who states that “responsible companies are taking proactive steps to minimize the likelihood that their generative AI tools inadvertently violate the right of publicity.” Some examples of these steps include “attempting to filter out celebrity images from those used to train the generative AI models and filtering prompts to prevent users from requesting outputs that are directed to celebrity-based NIL.”

The case is Kyland Young v. NeoCortext, Inc., 2:23-cv-02496 (C.D. Cal.).