In 2014, Amazon’s sales were inching towards $90 billion and the e-commerce giant that Jeff Bezos had founded 20 years prior in the garage of his home in Washington state had plans of expansion in the works. Within a year, the Seattle-based platform would enable China-based entities to sell directly to Amazon shoppers, and increasingly implement efforts, such as a top-of-the-line logistics system and vast network of fulfillment centers, to make it easier for merchants to become exporters.

The result was significant from the outset. Sales from Chinese sellers more than doubled in 2015, alone, boosting Amazon’s sales by a whopping 20 percent, and enabling its total revenues to blaze past the $100 billion mark for the first time. Shareholders were pleased for more reasons than one; in addition to guaranteeing revenue growth thanks to its vast new pool of third-party sellers, Amazon’s move to open its doors to sellers in East Asia enabled it to insure that it would never be lacking in terms of supply for its marketplace platform, from which it derives more than half of its revenue.

Amazon inevitably welcomed another outcome, though. By growing its seller base, particularly in China, which has, for years, consistently held the title of the counterfeit-manufacturing capital of the world, Amazon “cleared the way for the counterfeiters and scammers that have long plagued Chinese e-commerce sites to not only rip off the intellectual property of Western brands but to compete directly against them in the same marketplace, often on the same pages,” says China-focused writer Wade Shepard.

And that is precisely what has occurred.

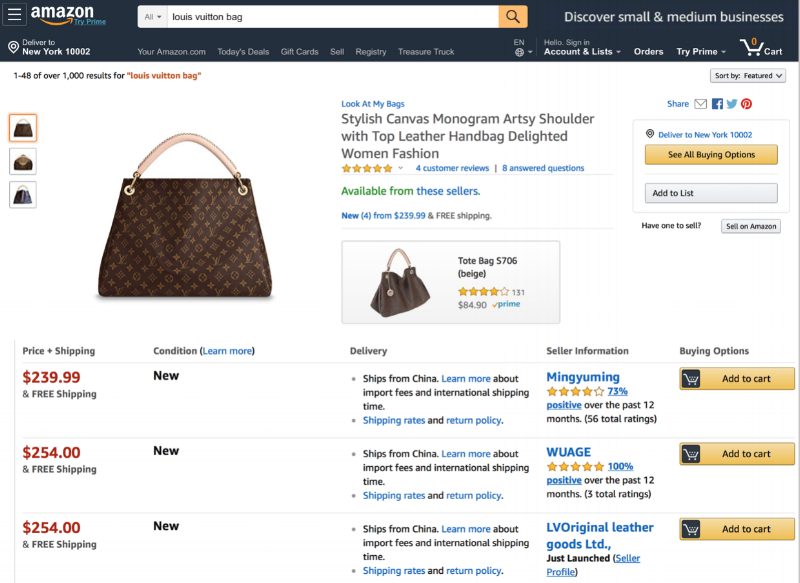

Thanks to its 5 million-plus global third-party sellers, Amazon boasts a seemingly endless supply of products, including luxury ones. There are Louis Vuitton Artsy bags, Chanel flap bags, and countless pairs of Balenciaga Triple “S” sneakers. Street style-centric Off-White belts can be found en masse on the platform, as can buzzy Supreme wares. Even highly-sought after Birkin bags are in the mix. No small number of these products are brand new, and no small number of these products are fake.

The ease with which consumers can locate and buy counterfeit or otherwise infringing goods – paired with the prevalence of fraudulent, paid-for reviews that have been known to crowd the comments sections of many third-party sellers’ pages – sheds light on why Amazon has been plagued with an increasing amount of complaints from brands, big and small, about the efforts it takes (or does not take) to clean up its platform.

But there is more to it than that.

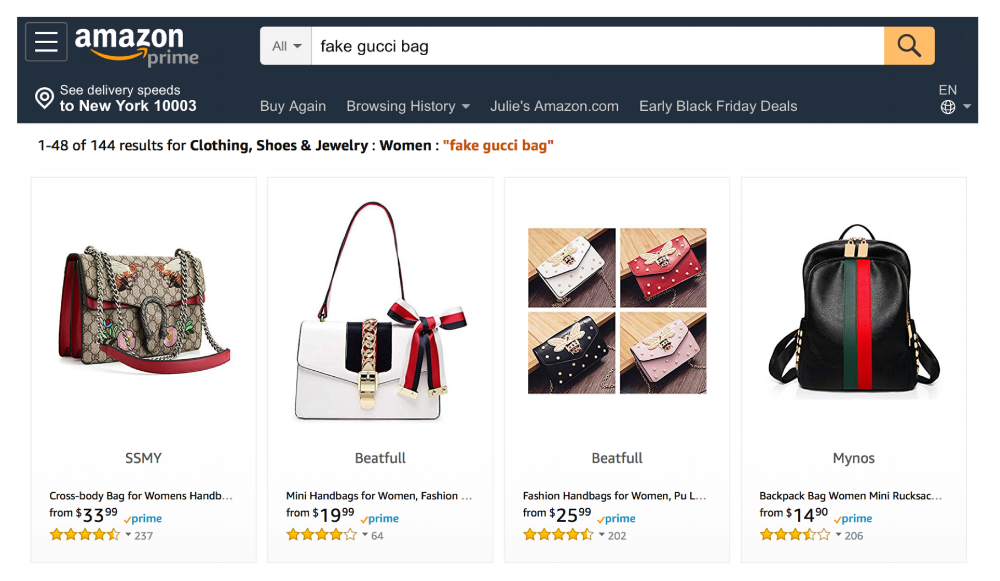

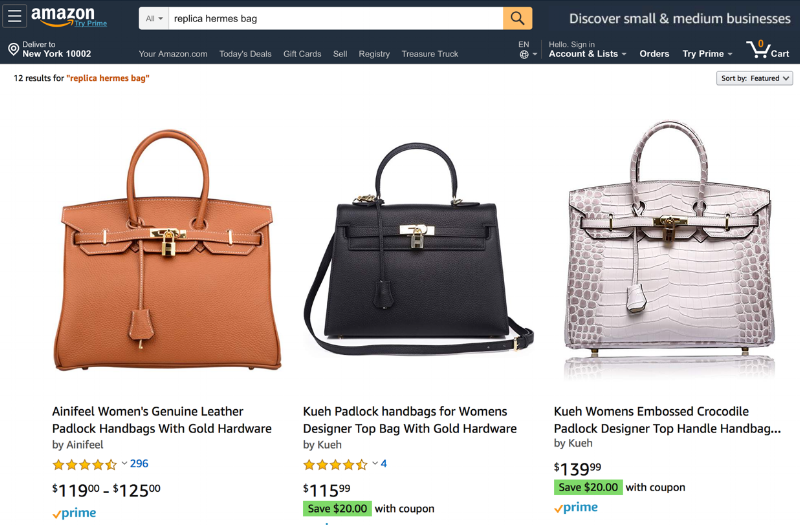

Even more telling than a search for a “Louis Vuitton bag” and the dozens of counterfeits (i.e., products that depict another’s federally registered trademark or one that is “substantially indistinguishable” from another party’s trademark on the same types of goods for which the trademark holder has registered its mark) that show up as a result, is what happens when a consumer searches for, say, a “fake Gucci bag.”

The result is the same: pages and pages of products show up on the screen. Most make use of at least one of the Italian design house’s federally protected trademarks, whether it be the interlocking “G” print or its red and green, and red and blue striped marks, meaning that they are counterfeits.

There are even counterfeit goods included in “Sponsored” listings and those spotlighted as “Amazon’s Choice.”

On a micro level, these results reveal that the $1 trillion giant enables third-party sellers to use brands’ trademark-protected names as meta tag keywords in connection with their product listing.

The use of brand-centric meta tags or keywords is not legally problematic when the resulting products are authentic. Similarly, courts, including the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals (in the MTM watch case), have held that Amazon is not running afoul of federal trademark law for providing a list of “aesthetically similar” products “manufactured by [a brand’s] competitors” when consumers search for a brand that is not available on Amazon, as long as the platform utilizes clear labeling as to the maker of those products.

It is problematic, however, when Amazon enables third-party sellers to use brands’ trademark-protected names as meta tags to offer and sell counterfeit or otherwise infringing products.

More broadly, these search results indicate that behind Amazon’s public relations campaign – which centers on its efforts to eradicate fakes from its platform, its practice of “invest[ing] heavily, both [in terms of] funds and company energy, to ensure our policy against the sale of [counterfeit] products is followed,” and its policy of prohibiting (on paper, at least) users from “providing misleading or irrelevant catalog information (title, bullet points, description, variations, keywords, etc.)” for listed products – there are some glaring inconsistencies.

Some of these points of oversight could prove relatively easy to remedy for a company with Amazon’s resources and capabilities; it would not be difficult, after all, for Amazon’s backend algorithm to be set to identify product titles and/or descriptions that contain specific words, such as “fake,” “knockoff,” “replica,” etc. A set of code could ensure that such products are flagged immediately and prevented from being listed on Amazon’s platform, not merely addressed after the fact (i.e., after a brand files a notice and takedown request with Amazon).

Similarly, Amazon could implement – and to some extent is said to be working on – a system that requires third-party sellers to prove that they are authorized to sell branded products when they are offering more than a certain quantity of goods. Still yet, Amazon could more thoroughly vet the products it lists as “Sponsored” or “Amazon’s Picks” (i.e., the products it promotes in exchange for monetary compensation) to at least attempt to ensure that these products are not counterfeit.

But as of now, the platform is rife with listings – and in many cases, dozens of listings from individual sellers – offering counterfeit goods, a move that could be, as some have argued, entirely intentional on Amazon’s part.

“Amazon is making money hand over fist from counterfeiters,” Chris Johnson, an attorney at Johnson & Pham LLP, which focuses on intellectual property and brand enforcement and represents clients including Forever 21, Adobe and OtterBox, told CNBC, which is likely why he says Amazon has “done about as little as possible for as long as possible to address the issue.”

Mr. Johnson is hardly alone in his sentiment. In September, the Los Angeles Times pointed to “two dozen brand owners, e-commerce consultants, attorneys, investigators and public policy experts,” who claim that Amazon has “actually thrived [by allowing the sale of fake goods]” thanks to the transaction and shipping fees that these sellers say to the platform “just like legitimate businesses” and that the platform simply is not doing enough to fight fakes.

The American Apparel and Footwear Association, a prominent Washington, D.C.-based trade organization that boasts members, such as Calvin Klein, Jimmy Choo, Marc Jacobs, Stuart Weitzman and Ralph Lauren, among others, has urged the U.S. Trade Representative to add Amazon’s intentional arms to its annual list of bad actors for this exact reason.

Others – ranging from multi-national giants, such as Mercedes Benz’s parent company Daimler, to individuals like Casey Hopkins, whose industrial design firm Elevation Lab has been the target of widespread counterfeits on Amazon – have argued that as a result of its failure to do more to stomp out counterfeits and protect rights holders, Amazon is legally complicit in its third party sellers’ foul play.

In a lawsuit filed last year, Daimler asserted that Amazon has repeatedly failed to “establish processes that would better detect and deter infringement.”

By opting to not take more robust steps to weed out counterfeit goods, Amazon is, according to Daimler, “opening the door for masses of counterfeiters and scammers to exploit the system at the expense of legitimate brands and customers alike.” And Amazon, which was valued at more than $1 trillion this fall, is making a whole lot of money in the process.

But do not take their word for it, search for a “fake Gucci bag” on Amazon for yourself and see what happens. The results are quite telling.