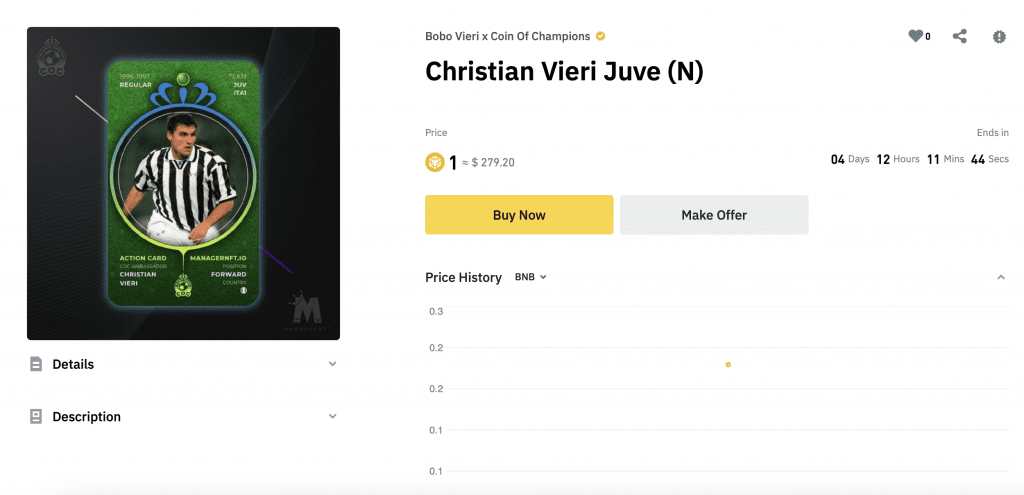

An Italian court handed Juventus FC a win in the most recent round of a legal scuffle over non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”). In an order this summer that was recently made final in lieu of an appeal, the Rome Court of First Instance granted the Turin-based football club’s bid for a preliminary injunction, barring Binance-hosted Blockeras s.r.l. from offering up NFTs that make use of the Italian club’s trademarks, including the Juventus and “Juve” word marks, as well as the design of its two-star-bearing black-and-white jersey. The court’s order follows from Juventus filing suit against Blockeras earlier this year, accusing the fantasy football game platform of infringing its trademarks by way of NFTs linked to trading cards featuring former Juventus player Christian “Bobo” Vieri.

In what is being characterized as “the first known judgment by a European court holding that NFTs reproducing a third party’s trademarks without authorization” amount to trademark infringement and warrant an injunction, the Court of Rome held that by minting and selling 68 NFT cards (from which it generated nearly $36,000), Blockeras ran afoul of Juventus’ trademark rights. (While Blockeras entered into an agreement with Vieri to use his likeness for the cards, it did not receive authorization from Juventus to use its marks.)

Some Notable Takeaways

In determining that Blockeras’ use of the Juventus marks is likely to cause consumers to be confused about the nature/source of the NFTs, and thus, siding with Juventus, the Court of Rome provided a number of notable takeaways for players in the NFT space – shedding light on the extent to which NFT-specific registrations are necessary and the distinction between NFTs and the assets tied to them.

Primarily, the court shot down Blockeras’ argument against an opposition, in which it asserted that an injunction should not be granted because, among other things, Juventus does not have registrations for the trademarks at issue for use on “downloadable virtual goods.” Unpersuaded, the court held that the Juventus trademarks are well known given that the club is the “the most successful Italian football team,” and as a result, it is not necessary to consider whether the marks are registered for use on “digital objects” or even more specifically, on “digital objects certified by NFT.”

Even if that were an issue, Juventus maintains registrations for its marks in Class 9 for use in connection with “digital downloadable publications,” which would suffice, according to the court. At the same time, the court also stated that Juventus “proved that it has become active in the field of … online games that are based on blockchain technologies and on the use of cryptocurrencies and/or NFTs through agreements with [global fantasy football game platform] Sorare.” (And beyond that, the court noted that the evidence on file shows the existence of “widespread merchandising activities [by Juventus] in various sectors (clothing, accessories, games) carried out online … with the use of the marks in question, and the company’s presence on the main social networks,” which also shows that it is using its marks in the digital world.)

The court’s determination here is in line with “the current mainstream approach that registration in Class 9 would [only] be required for non-well-known trademarks in order to obtain protection against infringing NFTs,” according to Trevisan & Cuonzo attorney Lorenzo Battarino. (It also mirrors our earlier arguments that despite a flood of companies rushing to file applications for registration for their marks in the quintessential metaverse classes, big-name brands likely do not need trademark registrations for goods/services that they are readily dealing in in the “real world.”)

Another critical takeaway comes by way of the court distinguishing between NFTs – or digital tokens recorded on the blockchain – and the digital images that are commonly tied to NFTs. This can be seen in the language of the injunction, which prohibits Blockeras from, among other things, engaging in any further “production, marketing, promotion and offer for sale” of the NFTs, as well as “the digital contents associated therewith.” The scope of the injunction seems to suggest that the NFTs, themselves, “have legal autonomy as compared to the images or [other] data associated with them,” Battarino says.

Some Broader Context: Other cases have paid a fair amount of attention to the potential token vs. token-tied-content dichotomy, with MetaBirkins creator Mason Rothschild, for example, arguing in response to the trademark complaint filed against him by Hermès that the NFTs, themselves, are merely a way to “authenticate” – and thus, are separate from – his artworks. StockX has similarly emphasized the difference between NFTs and any assets tied to them in the lawsuit waged against it by Nike. Meanwhile, Hermès has argued that its complaint is “about the NFTs, not necessarily the images associated with them.”

Reflecting on the court’s decision, which Blockeras did not appeal (it had already stopped marketing the NFTs), Battarino asserts that it “still leaves some questions open as to how such innovative orders may be effectively enforced by IP rights owners (e.g., in terms of the role of platforms hosting the infringing NFTs and related content, enforcement on the secondary market, assessment of damages, etc.).” Though, he states that there is “no doubt” that related litigation will arise and courts will inevitably be called on to resolve such outstanding issues.

The case is Juventus F.C v. Blockeras s.r.l.., No. 32072/2022.