Hermès is pushing for an early win in its lawsuit against the creator of non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) marketed as “MetaBirkins.” In a motion and memo of law in support lodged with the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York on October 8, counsel for the French luxury brand argues that it is entitled to summary judgment on its federal and state law trademark infringement claims, as well as its trademark dilution claim, marking the latest development in the headline-making case that Hermès filed in January, accusing Rothschild of “attempt[ing] to capitalize on the goodwill of a leading luxury brand … and one of its most iconic trademarks and products,” the Birkin.

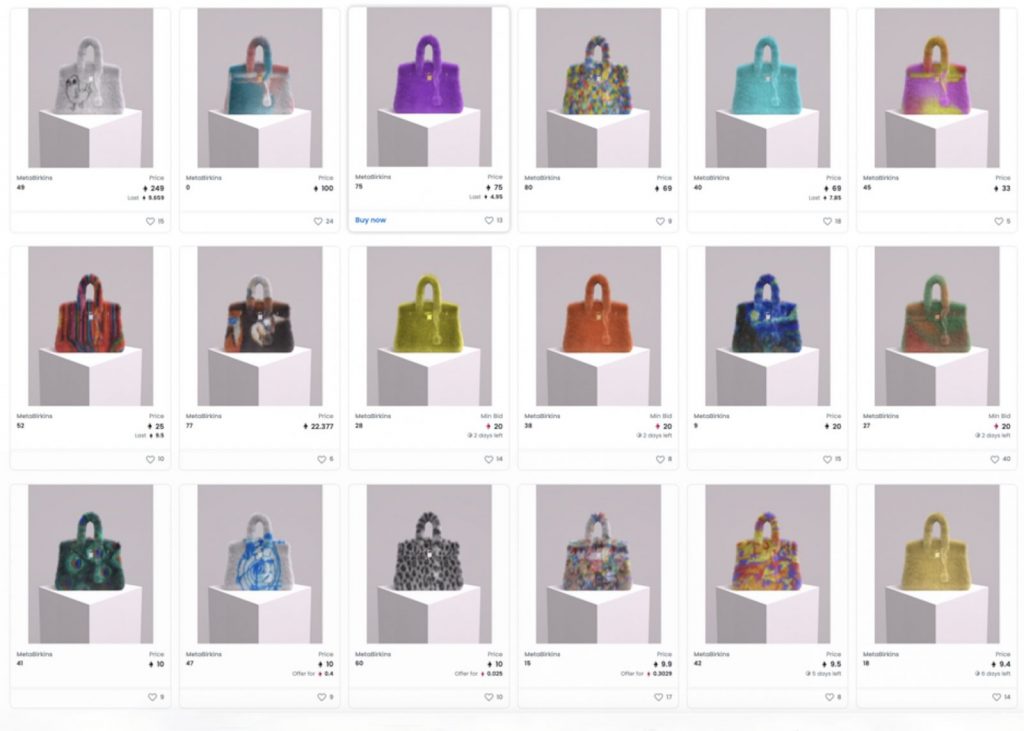

Setting the stage in its summary judgment bid, Hermès asserts that in December 2021, Mason Rothschild began selling the MetaBirkin NFTs. In addition to co-opting its federally registered “Birkin” trademark, Hermès holds that the images that Rothschild tied to the NFTs “appropriate the design elements (including shape and other features) of the trade dress covering [its] BIRKIN handbags.” After it “objected to” the MetaBirkins NFTs, Hermès maintains that Rothschild argued that the project amounts to “artistic expression,” and that Hermès is “trying to stifle his art.”

Hermès also contends in the newly-filed memo that while “Rothschild’s unlawful use of [its] trade dress and imagery is an aggravating factor, it was [his] unauthorized use of the BIRKIN name for NFTs … that gave rise to this action.” As such, the primary issue is Rothschild’s use of the Birkin trademark “to refer to and promote the NFTs themselves,” (i.e., the underlying smart contracts) which Hermès claims “have value separate and apart from any associated images.” (This is an interesting issue, and one that is simultaneously being explored in the Nike v. StockX case.)

On this point, counsel for the Birkin bag-maker states that “it is important to note that Hermès’s complaint is about the NFTs, not necessarily the images associated with them.” The brand attempts to bolster its argument here, asserting that, among other things, “the METABIRKINS smart contract assigned the name ‘METABIRKINS’ to NFTs before they were associated with any images,” which means that Rothschild can “change the digital files associated with the METABIRKINS NFTs at any time,” including with “a 3D file compatible with any platform.” In other words, Hermès says that “the digital images are not permanent and can be easily replaced, as Rothschild already did after minting, when the image associated with the NFTs was changed from a shrouded object to the digital BIRKIN handbags.”

“Clear and Undisputed”

With that background out of the way, Hermès alleges that its claims for trademark infringement and unfair competition are “clear and undisputed,” and mirroring earlier arguments, it points to the test described in Gruner + Jahr USA Publ’g v. Meredith Corp. as the appropriate one for analyzing Rothschild’s alleged infringement. The two-prong Gruner test asks: (1) whether the plaintiff’s mark is entitled to protection, and (2) whether the defendant’s use of the mark is likely to cause consumer confusion (applying the Polaroid factors to assess likelihood of confusion).

On the first point, Hermès maintains that “it is undisputed that [it] is one of the most iconic luxury brands known for its luxury goods,” and that its BIRKIN word mark is “federally registered, incontestable, and continuously used since 1986.”

Moving on to the second prong, Hermès argues that Rothschild “used ‘METABIRKINS’ to identify the collection of NFTs that he offered for sale” in a number of ways that amount to use of the mark as a mark in commerce. At the same time, Rothschild’s “commercial use of the METABIRKINS mark is likely to, and already has been shown to, cause confusion,” according to Hermès.

Despite the court “previously indicat[ing] that the digital images of handbags” that are associated with the NFTs “‘could constitute … artistic expression,’” and thus, use of the Rogers test (to balance trademark and First Amendment protections) was necessary, Hermès claims that “the undisputed facts developed since” show that “the Polaroid factors provide the applicable framework without the need to balance any First Amendment concerns.” Even if the Rogers test does apply, and “MetaBirkins” is found to be artistically relevant (the first prong of that test), Hermès argues that Rothschild does not meet the second prong, as he has “made various explicit statements that misled the public and the press into believing his NFTs were associated with Hermès.”

Turning its attention to the eight Polaroid factors, Hermès asserts that “unlike most trademark cases, the salient facts … are undisputed,” and ultimately, declares that each of the factors weighs in its favor. Among some of the points that Hermès makes here …

Similarity of the BIRKIN Mark and METABIRKINS Mark – Hermès states (as it has in prior filings) that “instead of dispelling confusion, Rothschild’s modification [of the Birkin mark]” with the “addition of the generic term ‘META’ to [the] BIRKIN Mark creates the explicitly misleading impression that Hermès … is offering BIRKIN handbags in the METAverse. This confusion is exacerbated by the appearance of the digital handbag, which looks like a BIRKIN handbag.”

Competitive Proximity of BIRKIN Handbags and METABIRKINS – “It is undisputed,” according to Hermès that it and Rothschild “market the same types of goods – a luxury handbag.” Despite the court’s earlier statement in its memo order that the parties “do not dispute” that the MetaBirkins are “digital images of … Birkin bags, and not virtually wearable Birkin bags,” Hermès contends that “similar to real life BIRKIN handbags, the METABIRKINS NFTs as minted were immediately usable in certain metaverses.” Adding to its attempt to show that Birkin bags and the MetaBirkins NFTs are competing products, Hermès states that Rothschild, himself, agreed that the “difference between [the real life and digital handbag] is like getting a bit blurred now because we have this new outlet, which is the metaverse, to showcase our product, showcase them in our virtual worlds, and even just show them online.”

Evidence of Actual Confusion – Rothschild’s promotion of METABIRKINS NFTs “caused precisely the confusion he intended,” Hermès asserts, stating that shortly after he released the MetaBirkins, “commentators and consumers … and even intellectual property attorneys all assumed that Hermès was involved with the METABIRKINS NFTs.” Such alleged confusion “created significant difficulties for Hermès, including its plans for legitimate NFT projects.” (Was Hermès really planning an NFT venture of its own? That is somewhat difficult to imagine.)

Beyond that, Hermès asserts that “Rothschild admitted that there was actual confusion” as to the nature/source of the MetaBirkins NFT, and “his agents and partners said the same.” And still yet, it points to a survey that it commissioned to “measure the likelihood of confusion between [its] BIRKIN handbags and the METABIRKINS NFTs.” The result “confirms actual confusion,” per Hermès, which states that the survey found “net confusion among the NFT audience of 18.7 percent.” This level of net confusion is “evidence of a substantial likelihood of confusion,” the brand claims.

Rothschild’s Bad Faith in Adopting METABIRKINS – While the majority of Hermès’ arguments here are redacted, the company claims that Rothschild created the MetaBirkins NFTs in bad faith, seeking “to capitalize on the goodwill associated with Hermès’s BIRKIN mark” and “make money by replicating those fashion brands and created ‘the same kind of illusion that [the BIRKIN handbag] has in real life as a digital commodity.’”

Sophistication of Consumers in Marketplace – “Rothschild’s consumers are well aware that brands have expanded into digital goods,” per Hermès. “However, as evidenced by consumers’ comments on social media and the survey Hermès conducted, consumers are not particularly sophisticated in determining whether the METABIRKINS NFTs were authorized, affiliated, or sponsored by Hermès.”

With the foregoing and the other Polaroid factors in mind, all of which it says tip in its favor, Hermès contends that there is no genuine dispute as to a material issue of fact, and thus, summary judgment on the infringement claims should be granted.

A Famous Mark

Hermès also calls on the court to grant summary judgment as to its trademark dilution claim, asserting that its “Birkin” trademark rises to the level of fame required to prevail on a dilution claim under the Lanham Act. (“[A] mark is famous if it is widely recognized by the general consuming public of the United States as a designation of source of the goods or services of the mark’s owner.”) “Hermès is well known for its iconic and universally known BIRKIN handbag, which was first sold in U.S. commerce in 1986,” the company claims, noting that even “Rothschild gushed about the BIRKIN handbag’s fame, noting that ‘there’s nothing more iconic than the Hermès Birkin bag,’ as it is a ‘holy grail’ handbag.”

Aiming to bolster its claim that the Birkin mark is famous, Hermès states that it “has sold over [a redacted amount] worth of BIRKIN handbags in the United States since 1986,” and in the past 10 years, alone, “has annually sold over [a redacted amount] worth of BIRKIN handbags in the U.S.” (For some context, Bernstein analyst Luca Solca previously estimated that Hermès makes/sells 70,000 Birkins every year, with a million-or-so already in circulation.)

“Many of the factual allegations underlying the Polaroid factors also support dilution,” Hermès argues: “The trademarks are highly similar; the BIRKIN Mark is strong and distinct; Rothschild acted in bad faith by adopting the METABIRKINS mark with the intent to create an association with Hermès and the BIRKIN Mark; and there has been actual confusion as to the association between the METABIRKINS collectible digital handbags and Hermès and its BIRKIN Mark” These facts “establish that Rothschild’s use of METABIRKINS is likely to cause dilution, harming Hermès’s goodwill and capacity to exploit and to use” the BIRKIN Mark in the metaverse,” counsel for Hermès claims.

Accordingly, Hermès states that summary judgment should also be granted as to its trademark dilution claim.

The brand’s motion comes in the immediate wake of Judge Rakoff refusing to certify Rothschild’s appeal of a May decision, in which the court denied Rothschild’s motion to dismiss Hermès’s claims that he “violated” Hermès’s trademark rights by way of his headline-making MetaBirkins project. In his September 30 opinion, Judge Rakoff determined that the issues at play in Rothschild’s appeal are not so “exceptional” as to warrant immediate appellate review, and thus, denied Rothschild’s motion in full.

The case is Hermès International, et al. v. Mason Rothschild, 1:22-cv-00384 (SDNY).