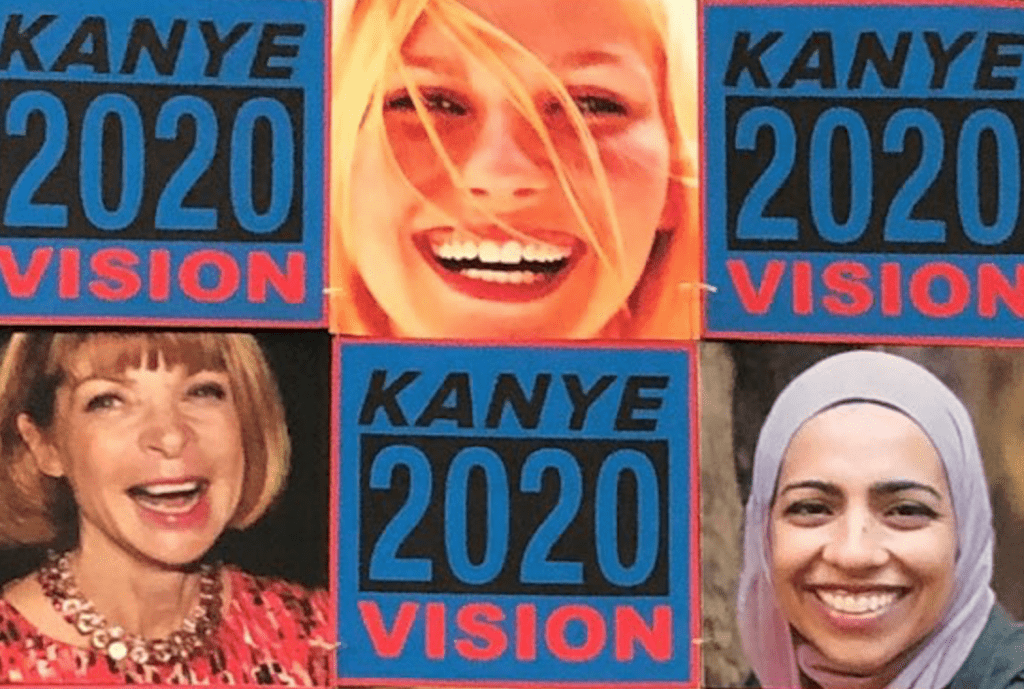

In the midst of a last-minute presidential campaign, one that has been rife with “reports suggesting that Republican-affiliated operatives are working to get [him] on the ballot in several states, part of a strategy to use [him] to siphon votes away from away from the major party candidates,” Kanye West posted what appears to be a campaign poster to his Twitter account on Tuesday. Alongside his “Kanye 2020 Vision” slogan, which is a close play on the logo of cult skate brand Vision Street Wear, the poster consists of an array of images, one features a laughing Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour, another depicts actress Kirsten Dunst by way of a photo from a 2002 Vanity Fair profile, and the list goes on.

As Vanity Fair’s Emily Kirkpatrick reported on Thursday, aside from Wintour and Dunst, the poster also includes “photos of singer Mike Yung, who was a semi-finalist on America’s Got Talent in 2017; Akhona, a man who appeared in a South African Gilette ad in honor of Women’s Day; Hena Din, a senior clinical research manager at the Allergy and Asthma Research center at Stanford University; a photo of a man at a 2017 pro-life vigil ahead of the March For Life; and [an array of] stock images,” including one of construction workers, among others.

It turn outs, the photo of Dunst has proven to be the most controversial one. On Thursday, the “Spider Man” actress posted a tweet of her own: “What’s the message here, and why am I a part of it?,” she asked. A representative for Dunst, who endorsed Senator Bernie Sanders for president back in March, confirmed to People magazine that she had not agreed to the use of her image. Meanwhile, a spokesman for Vogue revealed that “Anna has been a deeply committed supporter of the Democratic Party for many years, and is highly engaged in helping Biden/Harris win this November.”

Legally-protectable likeness is part of what is at play here, and it is (part of) what could turn an otherwise harmless(?) poster/tweet into a hypothetical legal battle.

A Right of Publicity Problem?

Since neither Dunst not her reps seem to have authorized Kanye to use a photo of her (i.e., her likeness) in a promotional capacity, the situation raises a red flag from a right of publicity standpoint. A state law doctrine, the right of publicity generally prevents the unauthorized commercial or promotional use of an individual’s name, likeness, or other recognizable aspects of one’s persona. West’s wife Kim Kardashian, for instance, has initiated a number of right of publicity cases over the years when others have used images of her without her authorization – from the $20 million one she filed against Old Navy back in 2011 to the more recent legal battle she lodged against fast fashion company Missguided.

In California, where there are common law and statutory causes of action for right of publicity violations, the state appeals court has held (in Eastwood v. Superior Court) that the common law elements typically include: (1) the appropriation of a plaintiff’s name or likeness to the defendant’s advantage, commercially or otherwise; (2) lack of content by the plaintiff; and (3) resulting injury to the plaintiff as a result. California’s right of publicity statute goes further, requiring that the use by the defendant be “knowing” and that there be a “direct connection between the use and the commercial purpose.”

Given that a photo that features Dunst’s likeness was, in fact, used without her authorization on the political poster, the issues in such a hypothetical case would likely turn on whether Kanye’s use of her likeness is for a “commercial” purpose or for “the defendant’s advantage, commercially or otherwise” (as opposed to falling within the bounds of the First Amendment). More than that, it is worth asking whether Dunst has been damaged as a result of such use.

In terms of the first point, when considering “commerciality,” advertising campaigns and things of that nature may come to mind, given that the California Statute (Civ. Code § 3344) defines “commercial use” as being “for purposes of advertising or selling, or soliciting purchases of, products, merchandise, goods or services.”

That is not exactly what is going on here; promoting a political candidate is likely not a commercial transaction (i.e., one that sees parties exchange goods/services for some type of remuneration). But the analysis does not stop there. As Loyola Law School professor Jennifer Rothmans sets out on her site, “Courts applying California law have allowed right of publicity claims in the context of non-commercial speech, including political campaigns, video games, comic books, and t-shirts.”

Similarly, Harvard University Berkman Klein’s center’s Digital Media Law Project states that that unlike the California state statute, “The common law right is not explicitly limited to commercial uses of a plaintiff’s identity.” Although, “the ‘less commercial’ a use is, the more that First Amendment concerns come into play.”

As for the issue of damages, in a hypothetical case, Dunst would almost certainly point to her reputation and call foul. In addition to remedying the financial harm that a plaintiff has suffered as a result of a right of publicity violation, courts may also take into account “injury to peace, happiness, and feelings,” as well as “injury to goodwill, professional standing, and future publicity value,” as the U.S. Court of Appeal for the Ninth Circuit has held in the past.

Here, Dunst may argue that the association with West’s political campaign has harmed her reputation and hindered her ability to commercialize her likeness on her own. Put simply, as a result of the fact that she appeared on the political poster, movie studios, consumer goods brands, etc., may think that she is in some way affiliated with – or endorses – “Kanye 2020 Vision,” thereby, making her less likely to get the jobs is in the running for, or maybe, has already booked.

Copyright, Too

Looking beyond the potential right of publicity cause of action at play for Dunst (and presumably the other individuals depicted on the poster), copyright law would also be a plausible claim, assuming that West did not license – or receive authorization to use – the images, themselves, (as distinct from the individuals’ likenesses) on his presidential banner from the respective copyright holders, whether it be Vanity Fair or Mario Testino (that would depend on the contract between the magazine and the photographer) for the photo of Dunst, Amy Sussman/Getty Images North America for the image of Wintour at Donna Karan’s Spring/Summer 2012 fashion show in New York, etc.

As for whether West’s use of the images would fall within the realm of transformative use, which would be a relevant defense for both right of publicity and copyright infringement claims, West might be able to fashion a creative argument on this front, particularly if his run is some elaborate and controversial art ploy or something in that vein. (As Vox’s Dylan Scott wrote recently, “As with much of West’s career, it is difficult to discern where the sincerity ends and the showmanship begins.”).

There is no telling what West is actually up to with his relatively newly-hatched presidential run. However, as University of Virginia Center for Politics’ Kyle Kondik told the publication, “I think we need to wait and see whether he actually makes the ballot in any crucial states before [making any] assessments.” The same would hold true for such a potential (although, almost certainly not viable) defense, as well.