Levi’s has named the owner of a recycled denim brand in a new lawsuit, claiming that by using the “Green Tab” name, he is running afoul of its rights in the mark, which is part of a family of “famous” marks, including its red tab. According to the complaint that it filed in a California federal court on Wednesday, Levi’s claims that Defendant David Connolly is on the hook for trademark infringement, dilution, and unfair competition for manufacturing, marketing, and selling products that bear “copies” of the Arcuate pocket-stitching trademark and of its “tab mark family,” namely, its “GREEN TAB” mark and green tab device.

In the newly-filed complaint, as first reported by Bloomberg, Levi’s claims that began to using its tab trademark (i.e., “a textile marker or other material sewn into the pocket seams or one of the regular structural seams of the garment”) on the rear pocket of its pants in 1936 to provide consumers with “sight identification” of its products. Since them, the San Francisco-based company states that it has consistently used the tab across its denim and “a variety of other clothing products,” and in a variety of colors, including green, making it so that consumers across the globe have come to recognize the tab mark as “signifying authentic, high-quality LEVI’S garments.” Even more than that, Levi’s alleges that “retailers and the public know refer to [its] iconic products as RED TAB, ORANGE TAB and SILVERTAB, among other references, depending on the color of the tab trademark.” And taken together, Levi’s contends that the various colored tabs and the “TAB-formative word marks” form the famous “Tab Mark Family.”

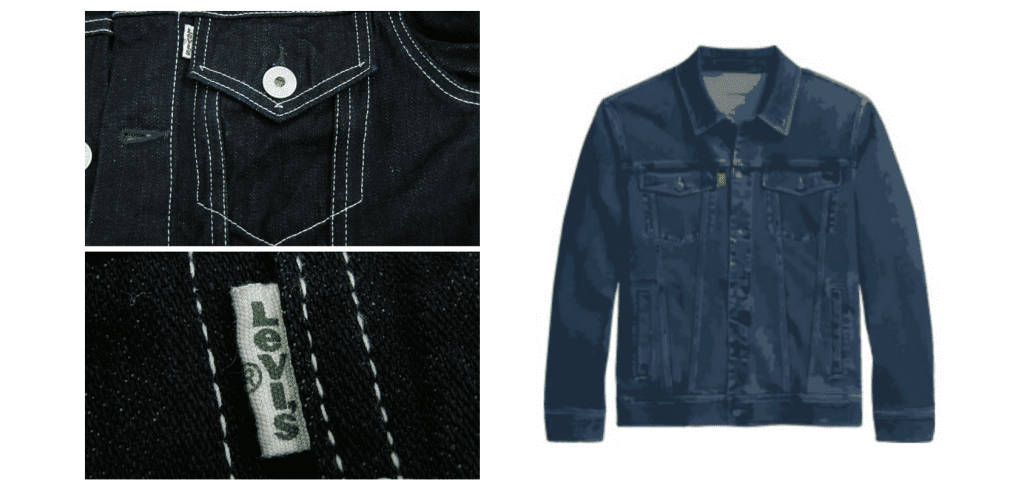

At the same time, Levi’s asserts that it has used its Arcuate trademark, which refers to the stitching pattern that appears on the back pockets of “almost every pair of Levi’s brand jeans,” continuously since 1873. (Fun fact: Levi’s claims that the Arcuate mark, which consists of “a distinctive pocket stitching design,” is the “oldest known apparel trademark in the United States still in continuous use.”)

And still setting the stage, the denim-maker contends that, for many years, it “has devoted substantial resources and effort to environmental initiatives and sustainability and has marketed services and products related to these initiatives using some or all of its famous trademarks.” Among these initiatives, Levi’s claims that it has “used, within its tab mark family, a green lettered tab to denote its efforts to create jeans produced with more climate friendly processes.”

Against this background, Levi’s claims that Connolly is “misappropriat[ing] its famous trademarks as symbols for his own jackets and denim recycling services,” including using “the GREEN TAB business name,” and in at least one mock-up, a green tab on denim jackets, which Levi’s contends “will lead the public to conclude, incorrectly, that he is or has been, or that his goods and services displaying or offered under the GREEN TAB mark are or have been, authorized, sponsored, or licensed by [Levi’s].” The likelihood of confusion is “exacerbated,” per Levi’s “by the fact that Mr. Connolly is using the GREEN TAB mark to promote and sell the same types of apparel products and sustainability services that [it] markets and sells in connection with its famous trademarks, including the tab mark family.”

While it “encourages some of the environmental initiatives associated with [Connolly’s] business,” Levi’s says that it “cannot tolerate [his] use of infringing trademarks to brand and commercialize those initiatives.” As such, Levi’s sets out federal and common law claims of trademark infringement, dilution, and unfair competition, and is seeking injunctive relief and monetary damages.

The most interesting issue in Levi’s newly-filed lawsuit is (in my opinion) is its argument about its “family” of tab trademarks, likening the various colored fabric tabs and the related word marks (which is where I scratch my head) to “a group of marks having a recognizable common characteristic, wherein the marks are composed and used in such a way that the public associates not only the individual marks, but the common characteristic of the family, with the trademark owner.” (As the Federal Circuit stated in the J & J Snack Foods Corp. v. McDonald’s Corp. case in 1991, “Simply using a series of similar marks does not of itself establish the existence of a family. There must be a recognition among the purchasing public that the common characteristic is indicative of a common origin of the goods.”)

Levi’s likely does not suffer from a lack of consumer awareness for its tabs; it states that it “has sold hundreds of millions of products, all over the world” that bear the fabric tabs and that account for “billions of dollars in sales.” In that same vein, it may not be an uphill battle for Levi’s to show that consumers connect the various colored tabs that appear on the pants pockets and that peek out from the breast pockets of its shirts (especially the red ones) with a single source.

What is more difficult to imagine is that Levi’s has strong of an argument when it comes to the various “Tab” word marks. It is worth noting that it is unclear from the complaint if Levi’s actually uses the “Green Tab” mark in the same way as it does with “Red Tab” (Levi’s has, for instance, named its customer loyal program “Red Tab”) – or if it exclusively makes use of a fabric tab that is green. It does not point to specific use of the “Green Tab” word mark and in fact, states that it “owns registered and common law rights in word marks that reference the history and heritage of the Tab trademark, including [its] RED TAB, ORANGE TAB, and SILVERTAB marks,” with no mention of green.

Such potential lack of use of – and rights in – the “Green Tab” word mark on its own (as distinct from the alleged family) is presumably why the denim-maker advances the “family” of marks theory, not unlike how McDonald’s did in the aforementioned case. In that case, the fast food giant argued that J & J’s use of “McPretzel” (a mark that McDonald’s was not using) infringed its family of “Mc” marks (think: McMUFFIN, McCHICKEN, McRIB, etc.), and the Federal Circuit held that McDonald’s had established a family of marks that consisted of a variety of generic food names preceded by the “Mc” prefix, even if it has not used or registered the “Mc” prefix by itself.

Also interesting is the broader adoption of sustainability-centric marks by brands in the fashion/apparel space. The Levi’s lawsuit comes as a growing number of brands are adorning certain wares – ones that stem from sustainability-focused initiatives – with specific indicators, which, in many cases, consists of plays on one of the brand’s existing marks. As we first reported early this year, the likes of Prada, Louis Vuitton, Valentino, and Moncler are among the brands that have introduced logos that suggest elements of sustainability, such as recycling, amid a surge in consumer awareness about and demand for sustainably made and marketed products. Levi’s green tab appears to fall pretty neatly into that category.

A rep for Connolly was not immediately available for comment in response to the Levi’s lawsuit.

The case is Levi Strauss & Co. v. David Connolly, 5:22-cv-04106 (N.D. Cal.)