A handful of “bad actors” are on the receiving end of a new Nike-initiated trademark infringement and dilution lawsuit. In a complaint that it lodged with the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York on November 30, Nike claims that By Kiy LLC and its founders Nickwon Arvinger and David Weeks, and Reloaded Merch and its owner Bill Omar Carrasquillo – as well as their common supplier Xiamen Wandering Planet Import and Export Co. – (collectively the “defendants”) are on the hook for “near-verbatim copying” of its Air Jordan 1 and Dunk sneakers, which it characterizes as “two of the most iconic and influential sneaker designs of all time … that have transcended sports and fashion and are coveted by sneakerheads throughout the world.”

According to the newly filed lawsuit, Nike alleges that By Kiy and Reloaded Merch are “currently promoting and selling” Air Jordan 1 and Dunk “knockoffs” in several colorways. Specifically, the two companies are allegedly co-opting the trademark-protected body design (including the exterior panels, stitching, eyelet placement, etc.) and designs of the treads on the soles of the Dunk and AF1 sneakers in furtherance of a “scheme to intentionally create confusion in the marketplace and capitalize on it.” (Nike points to registrations for the Dunk and Air Jordan trade dress – sans its famous swoosh logo – for use on footwear as the basis for its infringement and dilution claims.)

And there is, in fact, confusion at play, per Nike, which alleges that By Kiy’s and Reloaded Merch’s infringing offerings – some styles of which are labeled as “Air Kiy” and “Air Reves,” and “Air Omi,” respectively – have “led to initial interest confusion, post-sale confusion, and confusion in the secondary market. Given that the sneakers “travel in identical channels of trade and are sold to identical consumers as Nike’s genuine products,” Nike claims that “consumers and potential consumers [are likely] to believe that [the] infringing products are associated with and/or approved by Nike, when they are not.”

As evidence of consumer confusion, Nike points to a comment on one of Reloaded Merch’s Instagram posts, in which a consumer asks, “These are jordans?” – and claims that there are “consumers selling [the] infringing products on the secondary market refer to [them] as ‘Dunk[s],’ ‘Air Jordan 1s,’ ‘Jordan 1s,’ and ‘AJ1s.’”

At the same time, Nike claims that the “bad actors” at play here go beyond By Kiy and Reloaded Merch and include “various others in the supply chain, including manufacturers and distributors who provide material assistance to direct-to-consumer infringers.” Xiamen Wandering Planet Import and Export – which is “one such behind-the-scenes actor that provides material assistance to infringers,” per Nike – is also running afoul of the law by “manufacturing and supplying footwear bearing [Nike’s] trademarks and/or confusingly similar marks to direct-to-consumer sellers of knockoff Nike sneakers,” such as By Kiy and Reloaded Merch.

(Nike contends that Reloaded owner Bill Omar Carrasquillo “admits in several [YouTube] interviews that he and Kiy share the same manufacturer, which purportedly caused a conflict between the two.”)

Confusion, Control

Amid a bigger picture of Nike-initiated lawsuits, including customization-centric cases (which is not what is going on here, as the defendants’ sneakers do not consist of altered-but-originally authentic Nike shoes), the Nike lawsuit includes a number of notable issues/takeaways. Particularly interesting is Nike’s argument that as a result of the defendants’ sneakers, it “loses control over its brand, business reputation, and associated goodwill, which it has spent decades building.” This “loss of control” argument that Nike advances in the lawsuit seems to assume that people are confused and/or are opting to purchase the infringing sneakers instead of Nike footwear, and that its brand is being damaged as a result.

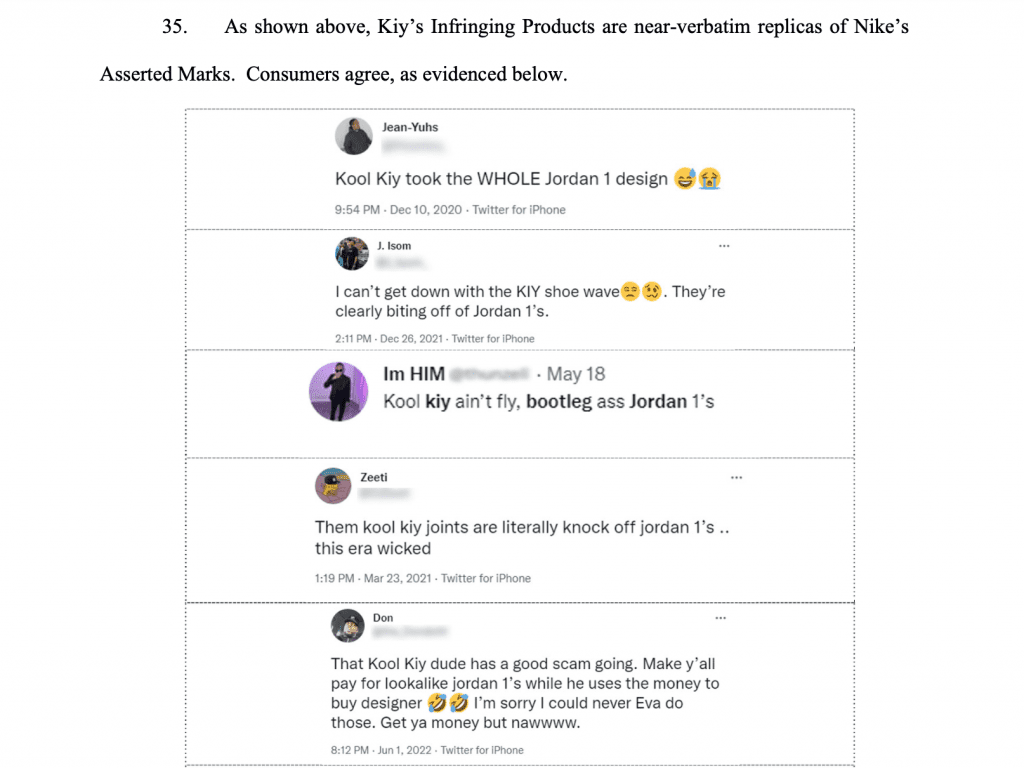

This raises a number of questions, including: Are people really confusing the defendants’ sneakers for ones that are authorized by or affiliated with Nike? Nike claims they are. But at the same time, some of the social media posts included in Nike’s complaint include comments that call out the defendants’ offerings as being copycat versions of Nike sneakers.

With this in mind, it is worth considering who the relevant consumer is here. Chances are that the likelihood of confusion is probably not significant among “sneakerheads,” who “covet” the Air Jordan 1 and Dunk sneakers, per Nike, and who – presumably – are well-schooled on what sneakers come from Nike, including as a result of a collaboration, for instance, and which do not. The potential for confusion is much greater when it comes to casual sneaker-buyers (i.e., those just looking for a new pair of sneakers and not logging on the Nike’s SNKRS app to get access to the latest drops). Nike would certainly argue that the relevant pool is the latter and that the level of attention that they pay in connection with a sneaker sale is low, and thus, they are likely to be confused about the source/nature of the defendants’ allegedly infringing wares.

Courts have routinely stated, as Judge David Carter of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California did in his preliminary injunction order in Vans v. MSCHF, that “typical purchasers of athletic shoes are ‘unlikely to exercise a high degree of care in selecting shoes.’” This is likely due, at least in part, to the price of the goods at issue, which are generally low compared to say, …. a car or a Rolex.

Another point worth noting: Nike argues that the damage at play goes beyond mere confusion. In particular, Nike alleges that the defendants are “building business[es] on the back of [its] most famous trademarks, undermining the value of those trademarks and the message they convey.” To this point, Nike states that in addition to “strict quality control standards for its products bearing [its trademarks],” which were not carried out here, it “maintains strict control over the use of [its trademarks] in connection with its products so that [it] can maintain control over its related business reputation and goodwill.”

Nike, for example, “carefully determines how many products bearing [its] trademarks are released, where the products are released, when the products are released, and how the products are released.” In other words, Nike claims that the defendants are interfering with its carefully crafted and meticulously maintained distribution model – which is an argument that companies – often in the high fashion and luxury segments – have made in lawsuits ranging from traditional trademark infringement suits (such as this one) to cases that have come out of the sale of authentic goods in the secondary market.

With the foregoing in mind, Nike sets out claims of trademark infringement, false designation of origin, unfair competition, and trademark dilution, and is seeking monetary damages, as well as injunctive relief. It has since followed up with another similar trademark lawsuit against a separate “bad actor,” Gnarcotic LLC, over its “intentional theft of Nike’s designs and associated goodwill.”

The case is Nike, Inc. v. By Kiy LLC et al, 1:22-cv-10176 (SDNY).