Nike is waging a new lawsuit against Lululemon, accusing its rival sportswear company of infringing a trio of the utility patents that it holds for its Flyknit technology. According to the relatively brief complaint that it filed with the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York on January 30, Nike claims that it “invests heavily in research, design, and development,” and routinely takes steps “to protect its innovative technologies, including by filing and obtaining patents around the world,” and that these “efforts are key to [its] success.” Among the patents that it holds are three that protect elements of the Flyknit tech, which Lululemon is allegedly infringing by way of its own footwear.

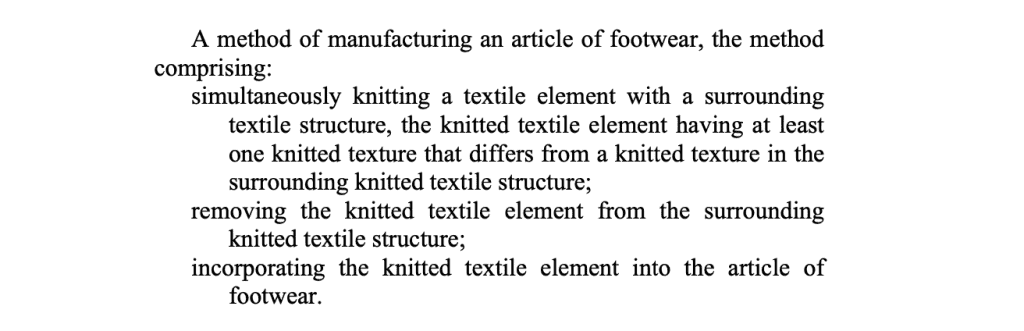

Specifically, Nike points to three patents (8,266,749; 9,375,046; and 9,730,484), which respectively protect: (1) “a method of manufacturing an article of footwear with a textile element, where the textile element is simultaneously knitted with a surrounding textile structure, and the textile element has a knitted texture that differs from the knitted texture in the surrounding textile structure;” (2) “an article with a textile element containing a plurality of webbed areas and tubular structures that are adjacent to each other and configured to stretch to move the webbed areas from a neutral position to an extended position when force is applied;” and (3) “an article of footwear with an upper including a flat-knitted element with a central portion having a domed, 3-D structure configured for extending over the top of a foot and that extends above the plane of a first and second side portion when in a flattened configuration.”

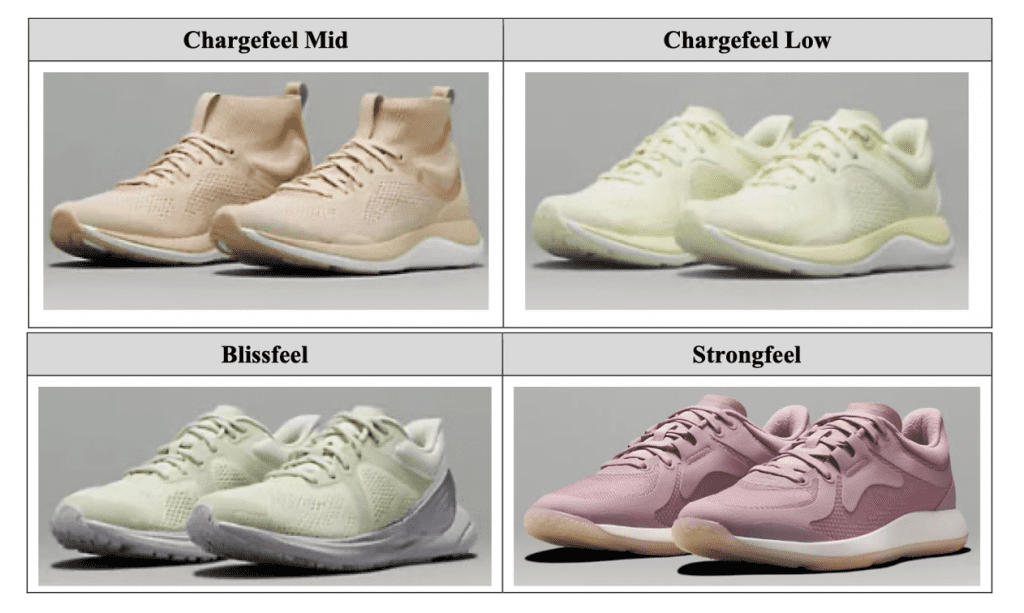

Without its authorization, Nike alleges that Lululemon is “mak[ing], us[ing], offer[ing] for sale, sell[ing], and/or import[ing] into the United States products that practice the claimed inventions of the asserted patents,” including the Chargefeel Mid, Chargefeel Low, Blissfeel, and Strongfeel footwear products.

Reflecting on its ‘749 patent, Nike claims that Lululemon imports into the U.S. that were manufactured using a process that “satisfies each and every limitation of claim 1” of that patent, as Lululemon “manufactures (or has manufactured for it) those shoes by simultaneously knitting a textile element with a surrounding textile structure, the knitted textile element having at least one knitted texture that differs from a knitted texture in the surrounding knitted textile structure; removing the knitted textile element from the surrounding knitted textile structure; and incorporating the knitted textile element into the article of footwear.”

The allegedly infringing sneakers “are not materially changed by subsequent processes after importation, nor do those products become a trivial or nonessential component of another product after importation,” per Nike, which claims that by offering up the allegedly infringing footwear Lululemon has “caused and will continue to cause [it] irreparable injury.”

With the foregoing in mind, Nike sets out three patent infringement claims, and is seeking injunctive relief and an award of damages against Lululemon “to compensate Nike for the infringement, but in no event less than a reasonable royalty as permitted under 35 U.S.C. § 284, together with prejudgment interest and post-judgment interest and costs.”

This is not the parties’ only pending scuffle. Nike sued Lululemon last year, alleging that it is infringing other patents in Nike’s portfolio via its Mirror Home Gym and accompanying mobile applications. According to the complaint that it filed in a New York federal court in January 2022, Nike claims that the Lululemon Mirror relies upon tech that is protected by six of the utility patents that it maintains for an interactive athletic equipment system, as well as for athletic performance sensing and/or tracking systems and methods, and monitoring fitness using a mobile device, among other things.

In response, Lululemon has argued that not only are Nike’s patents are not relevant to the Mirror, they are invalid on the basis that they are do not meet the subject matter and non-obvious requirements, among other things.

THE BIGGER PICTURE: The larger context here is rising competition in the sportswear space, which is inundated with a large number of brands vying for market share. Companies like Lululemon, which made its name in yoga-wear (read: sports-bra and leggings), are branching out into other aspects of activewear to gain access to greater revenue, and are challenging the traditional players in the space – like Nike – in the process. Lululemon, for one, is currently aiming to double its revenue to $12.5 billion by 2026, and is angling to do so by way of new products, as well as international expansion.

This overarching trend of expansion (and thus, increasing competition in an already fiercely competitive sector) into sportswear – or into different segments of the larger sportswear market – is not limited to Lulu, of course, and is coming in the form of fashion brands that are looking to cater to their existing consumers, as well as a potentially broader pool, via more diversified wares that complement their fashion-focused offerings.

Michael Kors, for example, landed on the receiving end of a trademark infringement, false designation of origin, and trademark dilution lawsuit that New Balance waged against it in 2021 over the fashion brand’s sale of sneaker styles that New Balance says are confusingly similar to its own. More recently, expansion and competition was one of the most important elements in the adidas v. Thom Browne trademark case, with adidas (unsuccessfully) arguing that Thom Browne’s use of a four-stripe motif was particularly problematic in light of the fact that Thom Browne, which made its name by way of tailored men’s fashion, has been increasingly engaging in “direct competition with [it] by offering sportswear and athletic-styled footwear that bears confusingly similar imitations” of its three-stripe mark.

The case is Nike, Inc v. Lululemon USA, Inc., 1:23-cv-00771 (SDNY).