“For decades it’s looked like no company could ever topple Nike, the $86 billion global sneaker juggernaut,” wrote GQ’s Matthew Shaer a couple of years ago. As of early 2015, adidas was still underperforming its top rival in the key U.S. sportswear market and confronting headlines that it was even trailing behind Under Armour, a far smaller player. Yet, over the past two years in particular, adidas has made a markedly successful play for the top spot and the German giant is not letting up.

“For decades it’s looked like no company could ever topple Nike, the $86 billion global sneaker juggernaut,” wrote GQ’s Matthew Shaer a couple of years ago. As of early 2015, adidas was still underperforming its top rival in the key U.S. sportswear market and confronting headlines that it was even trailing behind Under Armour, a far smaller player. Yet, over the past two years in particular, adidas has made a markedly successful play for the top spot and the German giant is not letting up.

In recent quarters, Adidas has managed to sustain double-digit sales gains, principally in the crucial North American market. As noted by adidas-Group CEO Kasper Rorsted in March, “The one market that we have traditionally been challenged in, North America, we have made fantastic progress in the past two years so we have great momentum.”

“Nike is still growing. Its dominant position atop the athletic footwear and apparel business remains secure,” Oregon Live’s Jeff Manning stated in November. “But adidas is growing faster. For the first time in recent memory, they’re grabbing market share from Nike.” And adidas is doing so by way of what analysts have called a “sweet spot at the crossroads of sports and pop culture.”

In addition to purely athletic shoes, the brand is banking on athleisure apparel, fashion collaborations, reissues of timeless classics (such as the Stan Smith and the Gazelle, among others), and the headline-grabbing YEEZY collection with rapper Kanye West, who first collaborated with Nike in 2009, but switched to adidas in 2013. It is worth noting that in terms of the latter element, Matt Powell, Vice President of Industry Analysis and the Sports Industry Analyst for New York-based market search firm, NPD Group, noted recently, “Adidas’ sales were negative for 2 years after signing West. Of the top 10 adidas shoes [in 2016], only one was remotely related to West.”

Regardless of the actual impact that such big-name collaborations have on the companies’ bottom lines – practically speaking, only sneaker-heads and/or fashion fanatics actually respond to such projects – the two rivals have sparred in terms of which could land more desirable collaborators.

In the past several years, alone, Nike has teamed up with former Givenchy creative director Riccardo Tisci, Berlin-based tech brand ACRONYM, Supreme, Balmain’s Olivier Rousteing, Off-White’s Virgil Abloh, Louis Vuitton’s menswear director Kim Jones, and designer John Elliott, among others. In addition to West, adidas has landed Pharrell, Alexander Wang, Raf Simons, Palace Skateboards, Nice Kicks, and Mary Katrantzou.

In addition to fighting for market share and the coolest designers/brand names, the two sportswear giants have been battling on-and-off for years in courts across the U.S. and abroad, in connection with patent-protected footwear designs, trade secret-stealing employees, and an array of other legal matters. While active litigation has long been a tactic of both adidas and Nike (against one another and against third parties), adidas has made headlines recently for the slew of lawsuits that it has filed against entities ranging from Elon Musk’s Tesla to fast fashion retailer Forever 21.

In light of what Forever 21 recently referred to as adidas’ “overly-aggressive” stance on legal matters when it comes to intellectual property (“IP”) – one that rivals that of a luxury brand, such as Louis Vuitton, which has been pegged in courts as a “trademark bully” due to its widespread efforts to fight any and all unauthorized uses of its valuable trademarks – how do these two rivals compare?

We looked at the IP litigation and trademark/patent opposition activity of both Nike and adidas over the past year or so (from January 2016 through April 2017 and compared it generally to comparable activity in 2014 and 2015) to see which brand is more assertively working to ensure that others are not infringing its valuable IP assets.

Here is what we found …

OVERVIEW

The majority of both parties’ legal activity consists of trademark infringement litigation and trademark opposition proceedings. For the uninitiated, before a trademark may be registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”), a number of requirements must be satisfied. The mark must be published in the Official Gazette – a weekly publication of the USPTO – in order to give others a chance to oppose it. After the mark is published, any party that believes it may be damaged by registration of the mark has thirty days from the publication date to file either an opposition to registration or request to extend the time to oppose.

Nike and adidas’ other legal activities take the form of patent infringement suits and inter partes review (“IPR”) proceedings, the latter of which refers to the procedure to challenge the validity of already-issued patents. In short: a party may seek to invalidate another’s patent based on allegations that it does not meet the requirements of novelty and/or non-obviousness.

ADIDAS

Given the strength of adidas’ famous three-stripe logo, it is not surprising that most of the German sportswear giant’s legal endeavors – both in terms of lawsuits and oppositions – center on that mark.

As set forth in almost all of adidas’ infringement suits, “Sixty-five years ago, adidas first placed three parallel stripes on its athletic shoes, and the three-stripe mark came to signify the quality and reputation of adidas products to the sporting world early in the company’s history.” In connection with this mark, adidas has held federal trademark registrations extending to clothing, footwear, and other accessories dating back to the late 1960’s. It also has federal rights in its leaf design mark, as well as an array of word marks for its name and various other phrases, such as “ADIWEAR,” “adiPRENE,” and “THE BRAND WITH THE 3 STRIPES,” among others.

Its IP infringement-specific litigation has, for the most part, been rather consistent, despite increased coverage of adidas’ “litigious” strategy by the media over the past couple of years. The brand has filed between 10 and 15 IP-specific suits per year since 2014, including trademark infringement suits against Forever 21, Sears, Kmart and Marc Jacobs in 2015, and a design patent infringement suit against Under Armour, also in 2015. In 2016, adidas filed trademark infringement suits against APL, ECCO, and Italian footwear brand Bally, and a patent infringement suit against Skechers.

So far in 2017, it has filed trademark infringement lawsuits against Forever 21 (after filing and subsequently settling a suit with F21 in 2014), Juicy Couture, Puma, and another against Forever 21 earlier this month. It filed a utility patent infringement suit against ASICS this year, as well.

The rest of adidas’ IP-specific suits tend to take the form of trademark infringement/counterfeit suits filed against the operators of networks of websites – often Chinese-owned – containing the “adidas” name in their urls and/or offering counterfeit adidas goods for sale. Such suits are commonplace among brand owners, particularly luxury brands, and tend to be filed somewhat routinely as part of a larger legal strategy.

While we have seen little change in the number of lawsuits filed by adidas since 2014, the number of IPR proceedings and trademark oppositions initiated by adidas has increased notably within this timeframe. In 2014 and 2015, adidas did not file any IPR proceedings, whereas in 2016, it filed 5.

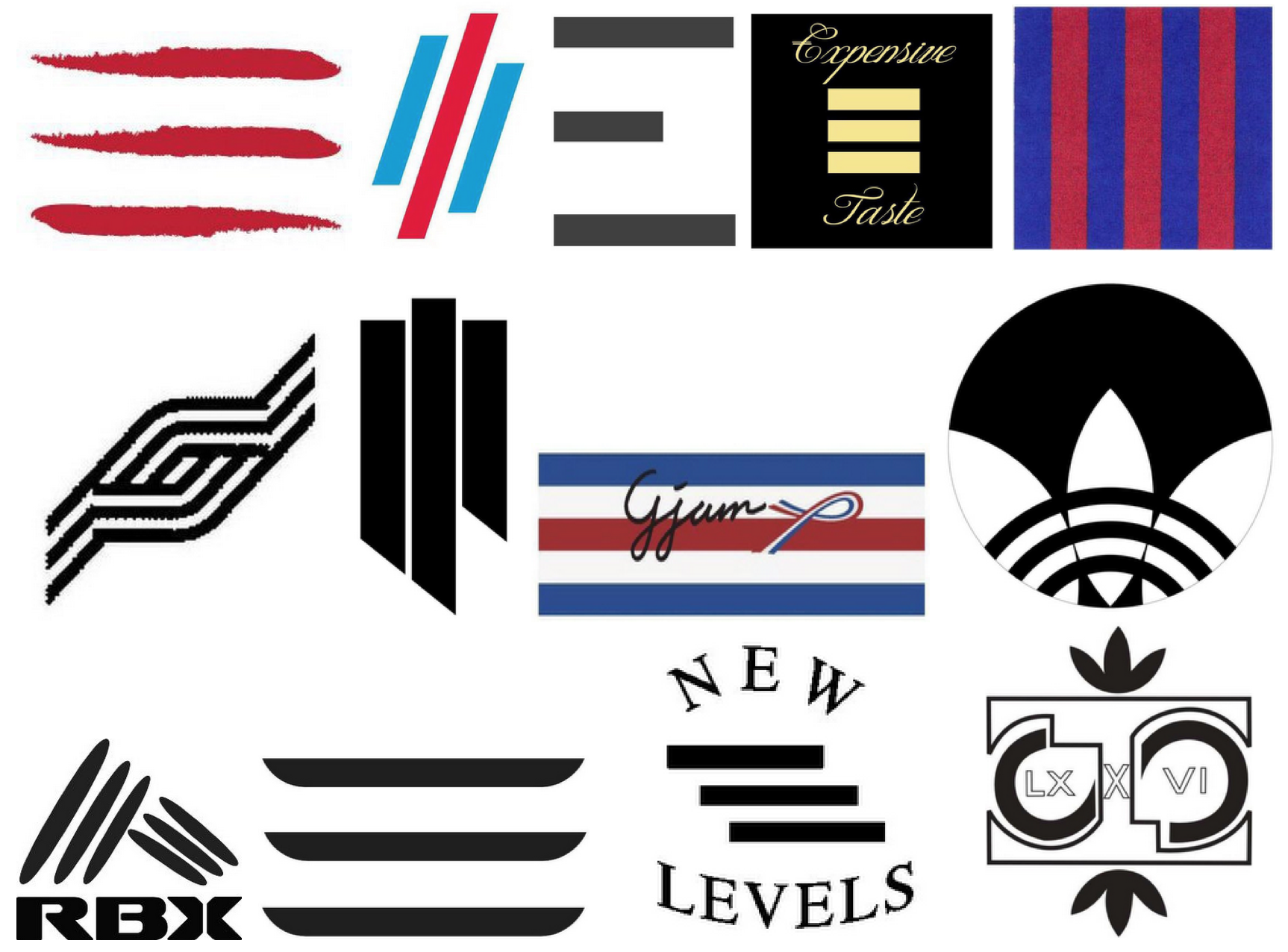

Some of the trademarks opposed by Adidas

Some of the trademarks opposed by Adidas

Its trademark opposition activity (both opposition filings and filing for an extension in order to file an opposition) has also increased consistently since 2014, with the brand filing less than 10 in 2014, roughly 20 in 2015, upwards of 30 in 2016, and over 21 so far in 2017.

The trademarks that adidas has filed to oppose and/or requested additional time to oppose range from those of apparel brands, including Seven for all Mankind and Ministry of Supply, to the marks of FC Barcelona, Tesla, and an organization seeking to register a mark for “God is Limitless” with a three-stripe design included therein.

NIKE

Unlike adidas, which is primarily concerned with its 3-stripe design trademark, the vast majority of Nike’s litigation and trademark oppositions stem from its “Just Do It” word mark. Nike has filed a smaller number of lawsuits than adidas, and the suits that it has filed largely center on patent infringement claims, plus a few trademark infringement/counterfeit suits against Chinese entities. The number of suits filed by Nike per year has decreased a bit since 2014, when it filed 6 or so suits.

Instead of filing throngs of lawsuits each year, Nike has focused its energy on procuring patent rights, in what Portland Business Journal has described as a “patent tear since it named Mark Parker CEO in 2006.” Nike has been issued roughly 50 patents so far in 2017; according to the USPTO database, adidas has been issued about 20 patents this year.

According Parker, the company’s patents have nearly doubled since 2009, burying Adidas and Under Armour in patents, as it looks to maintain its dominance with an avalanche of innovations in manufacturing and design while potentially toying with wearable devices. And if Nike’s increasing patent portfolio is anything to go by, big things are coming, as there is generally a correlation between a company seeking patent protection and its releasing innovative, game-changing products.

Globally, Nike has about 20,000 patents and pending patent applications. Adidas has roughly 2,500. Yet, despite the increased push for patent protection, Nike has engaged in only a small number of IPR proceedings over the years, filing less than 5 IPRs each year since 2014 – and none so far in 2017.

Additionally, Nike has engaged in a notable number of trademark opposition efforts over the past several years. The trademarks that Nike has filed to oppose and/or requested additional time to oppose include those from a cookie company (the mark at issue, “Just Dough It”), a range of consulting companies, and World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc. (“Just Bring It”), among others.

CONCLUSION

While adidas has been plagued with more press regarding its legal endeavors, the two companies fall on relatively common ground in terms of their legal activity as a whole.

Nike and adidas are well-matched in their pursuit of trademark filings – both parties have aggressively pursued them since 2014. While each has been granted roughly the same number of federal trademark or trade dress registrations over the past several years (5 for Nike in 2017 so far; 9 in 2016; 11 in 2015; and 10 in 2014. 6 for adidas in 2017; 12 in 2016; 8 in 2015; and 9 in 2014), adidas has filed a greater number of applications than Nike. For instance, in 2017, Nike has filed 3 applications thus far, whereas adidas has filed 10. In 2016, Nike filed 9 applications and adidas filed 20. (Note: adidas’ numbers do not take into account its recently offloaded golf division).

In terms of litigation, Adidas has undeniably filed more lawsuits than its most direct competitor over the past three years, and it has also filed more trademark oppositions. Nonetheless, the two are almost evenly matched on IPR proceedings.

Nike has been more aggressive in its patent-related efforts, whereas adidas has largely focused on trademark filings in recent years. This is not surprising given the range of new fashion-related adidas lines, among others, that it has introduced recently.

None of these findings are put forth to bolster the assertion that these brands’ legal strategies are static. As previously indicated, both companies have shown growth in various areas (adidas has amped up its patent-seeking activities over the past 10 years; whereas adidas has shown growth in the number of lawsuits it has filed against fashion industry entities) in recent years. Moreover, they are not at all immune to larger legal trends, such as an increased reliance on IPR proceedings following the implementation of the procedure in 2012.

Nevertheless, their individual patterns in enforcement strategies and intellectual property protections of choice – which neither party opted to comment on at this time – do give us some direction as to where they may be headed in the near future, which is particularly interesting given the increasing amount of competition within this space.