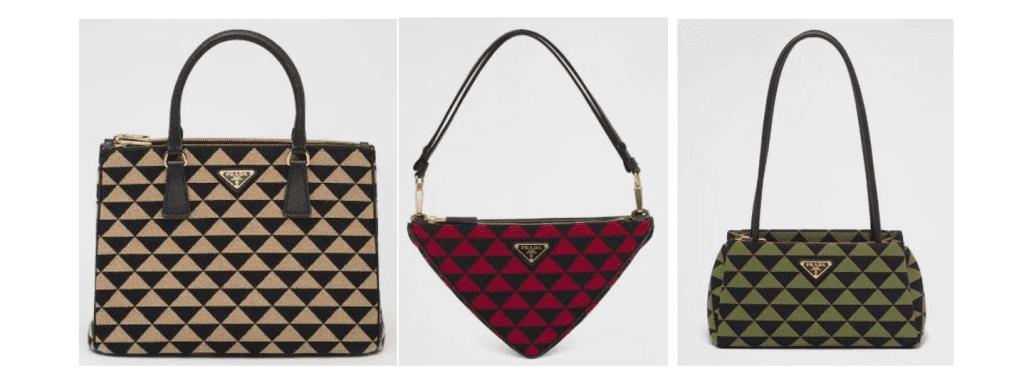

When you think of Prada (at least from a trademark perspective), what Prada itself refers to as its “iconic Triangle” comes to mind. Technically an isosceles triangle positioned upside down, the Prada Triangle is not only used in association with the word “PRADA” but is also employed as a 3D (think of, e.g., the Triangle Bag or Paradoxe perfume) and 2D self-standing shape. As far as the latter is concerned, the Triangle pattern has become somewhat unavoidable: it is used in connection with bags, scarves, garments, etc. The question thus becomes: can Prada’s Triangle pattern be protected as a trademark?

According to the EUIPO Second Board of Appeal (“Board”) in its decision on December 19 (R 827/2023-2), the answer is mostly not, at least if the argument is that such a pattern would be inherently distinctive.

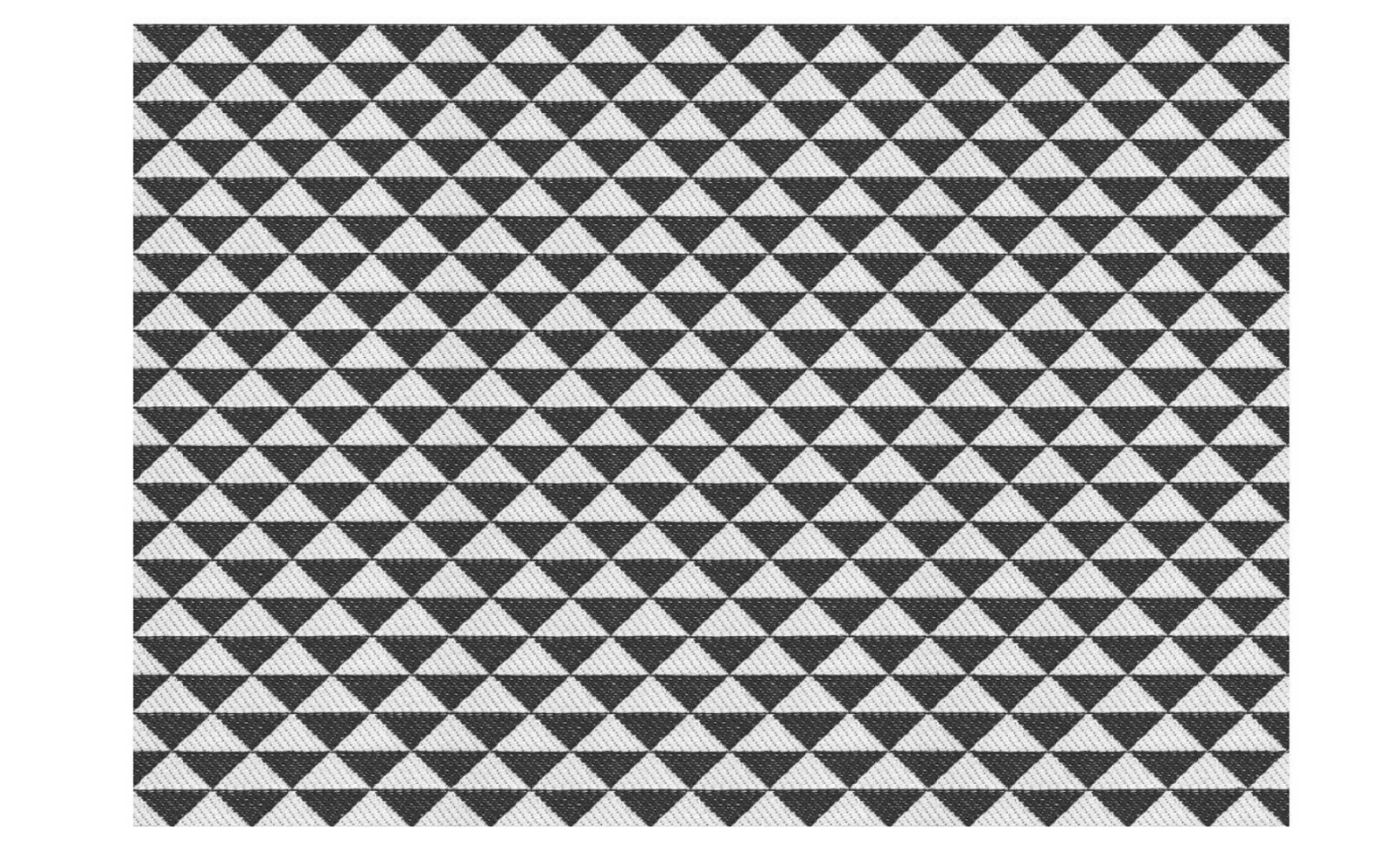

Background: In 2022, Prada filed to register the triangle pattern mark below as an EU trademark (EUTM; No 18683223) for goods and services in classes 3, 9, 14, 16, 18, 20, 24, 25, 27, 28, 35 of the Nice Classification. The EUIPO Examiner raised an objection pursuant to Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR – that is: lack of (inherent) distinctiveness – for most of the claimed goods and services.

Prada’s response was, among other things, that: (1) “the iconic upside-down isosceles triangle … has clearly become PRADA’s iconic signature;” (2) it has already successfully registered “Triangle” figurative trademarks with the EUIPO; and (3) it has used and promoted the pattern extensively. Eventually, the Examiner’s decision was to refuse registration in great part, including having regard to class 25.

More precisely, the application was only allowed for some goods and services, specifically: Class 9: Recorded and downloadable media, computer software, blank digital or analogue recording and storage media; LED [light-emitting diodes]; electronic publications; Class 20: Shells; yellow amber; and Class 35: Business management; business administration; office functions; auctioneering; business research; import-export agencies; marketing research; marketing studies; modelling for advertising or sales promotion; public relations; shop window dressing; organization of fashion shows for promotional purposes.

An appeal appeared unavoidable, and of particular interest is the point made by Prada that, in the fashion sector, it is an “established trade practice” to use patterns, with the result that consumers would attribute “an identifying function for pattern signs” when these are used systematically.

The Board’s Decision

In reaching its decision, the Board first provided a summary of relevant case law concerning pattern marks and their inherent distinctiveness, including the well-known leitmotif that, while there is no different or enhanced standard of distinctiveness, consumers may see less conventional marks like 3D shapes and patters as not communicating commercial origin in themselves unless they represent a significant departure from the norm and customs of the reference sector. The Board’s conclusion was that “the triangle-shaped pattern at issue is a basic and commonplace figurative pattern” which “does not contain any notable variation in relation to the conventional representation of triangle-shaped pattern and is the same as the traditional form of such a pattern.”

With regard to clothing, textiles, etc., in particular, the Board found that the Examiner had been correct to find that the pattern in question is “commonly used,” with the result that “the targeted public would merely perceive the repeating pattern as a typical design of decorative elements, as opposed to a trademark.” It would follow that the average consumer, when seeing the Prada pattern, would consider it “immediately and without further thought … as an attractive detail of the product in question, or as a banal decorative element, rather than as an indication of its commercial origin.” In short: the Triangle pattern would not be inherently distinctive.

But could the Prada pattern have acquired distinctiveness through use? The Board could not say, since Prada had “explicitly refrained from relying on Article 7(3) EUTMR.”

The Board also addressed Prada’s argument that, in the fashion sector, it is customary to use patterns as indicators of origin. The Board appeared to agree that that is the case. HOWEVER, that practice would serve precisely for a pattern to gain distinctiveness on account of the use made of the sign. In other words, the Board found Prada’s appeal not particularly well-construed and made a remark that reads a bit like a (figurative) slap on the wrist: “since in the case at issue the applicant is exclusively relying on the inherent distinctiveness of the mark applied for, this argument cannot succeed, since, in particular, as it has been concluded, the elements forming the sign applied for do not allow to conclude that it diverges from the norm or customs of the sector concerned.”

Reflecting on the Outcome

It appears that the Board could not have decided this case otherwise. The key to protection for a pattern like Prada’s as a trademark is not and (correctly) cannot be inherent distinctiveness, but rather acquired distinctiveness. That could be found to subsist here, and consumers would see such a pattern as an indicator of origin rather than as a decoration. A word of caution, however, is warranted, as proving acquired distinctiveness is by no means easy, especially considering that” (i) the relevant territory here is that of the European Union and (ii) so far, EU authorities, including the EUIPO and the General Court, have rejected the idea that something like a “luxury consumer” does exist.

One example, also concerning a rather simple fashion pattern mark, comes readily to mind: it is Louis Vuitton’s (unsuccessful) attempt to register its Damier Azur pattern as an EU trademark. As readers might recall, not too long ago, the General Court (T-275/21) put an end to the Damier Azur’s lengthy trademark saga, by concluding that Louis Vuitton had failed to demonstrate the pattern’s distinctiveness as acquired through use. Like the Board had also done (R 32/2022-2) around the same time as the General Court’s ruling in a decision concerning registrability of the shape of Dior’s Saddle bag, in the Damier Azur case the General Court also dismissed that idea, advanced by Louis Vuitton, that “throughout the European Union, consumers engage in homogeneous behavior as regards luxury brands, particularly because they travel and use the internet regularly”

At this point for Prada the only (sensible) card to play (and the only card that it should have played from the outset) seems to be claiming and demonstrating acquired distinctiveness of its Triangle mark, with the awareness, though, that many worthy fashion brands have tried and fallen on this front already.

Eleonora Rosati is Professor of Intellectual Property Law and Director of the Institute for Intellectual Property and Market Law (IFIM) at Stockholm University. (This article was initially published by IPKat).