Districts in northern Tanzania and southern Kenya are home to the Maasai, one of the the most widely copied groups to date. Turns out, the Maasai have somewhat recently become aware that brands are “profiting at their expense,” namely, by using the Maasai name without the authorization to do so. As a result, Maasai leaders came together for a two-day presentation on intellectual property a couple of years ago and have since embarked on a fight to claim their IP rights.

The result has come in the form of the Maasai IP Initiative, which “is dedicated to reclaiming the Maasai ownership of its famous iconic cultural brand by enabling the Maasai tribe to take more control over their own Intellectual Property.”

While over 10,000 companies have reportedly used the Maasai name on products in the past, Ron Layton, a New Zealander who specializes in advising developing world organizations on copyrights, patents, and trademarks, says, “Six companies have each made more than $100 million in annual sales during the last decade using the Maasai name. In 2003, Jaguar Land Rover sold limited-edition versions of its Freelander called Maasai and Maasai Mara.

Layton continues on to note, “Louis Vuitton’s 2012 Spring/Summer men’s collection [pictured above] included scarves and shirts inspired by the Maasai shuka. The shoe company Masai Barefoot Technology, bedding by Calvin Klein, shirts and trousers by Ralph Lauren, and cushions by Diane von Furstenberg have all been sold using the tribe’s name.”

As for whether the Maasai have a cause of action against such entities, Layton is working on it. He has spent the last four years on the Maasai case, helped by a $1.25 million grant from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Much of the effort so far has reportedly centered on creating an organization that could credibly represent the Maasai.

Layton estimates that if the Maasai play their cards correctly they could see licensing revenues as high as $10 million a year within a decade. The first step, he says, will be to seek out friendly companies who will publicly recognize [the Maasai’s] assertion of brand ownership. Layton says that Jaguar Land Rover has told him it plans to affirm the claim.

In a statement, Jaguar Land Rover confirmed it “has been engaged in constructive dialogue with representatives of the Maasai Intellectual Property Initiative with respect to the Maasai and Maasai Mara trademarks, which Jaguar Land Rover were the registered proprietor of.

Masai Barefoot Technology, which has recently come under new management, says it’s moving “away from using the ‘Masai’ word in its terminology which was the previous strategy of the past owners.” Calvin Klein says it no longer uses the Maasai’s name and has no plans to do so in the future. Diane von Furstenberg did not reply to requests for comment; spokespeople for Ralph Lauren and Louis Vuitton declined to comment.

A Larger Trend

This is not the first time a fashion brand has come under fire for using indigenous prints and trademarks without authorization to do so. The Navajo Nation famously filed suit against Urban Outfitters for making use of its name in connection with products, including underwear, jewelry, and flasks.

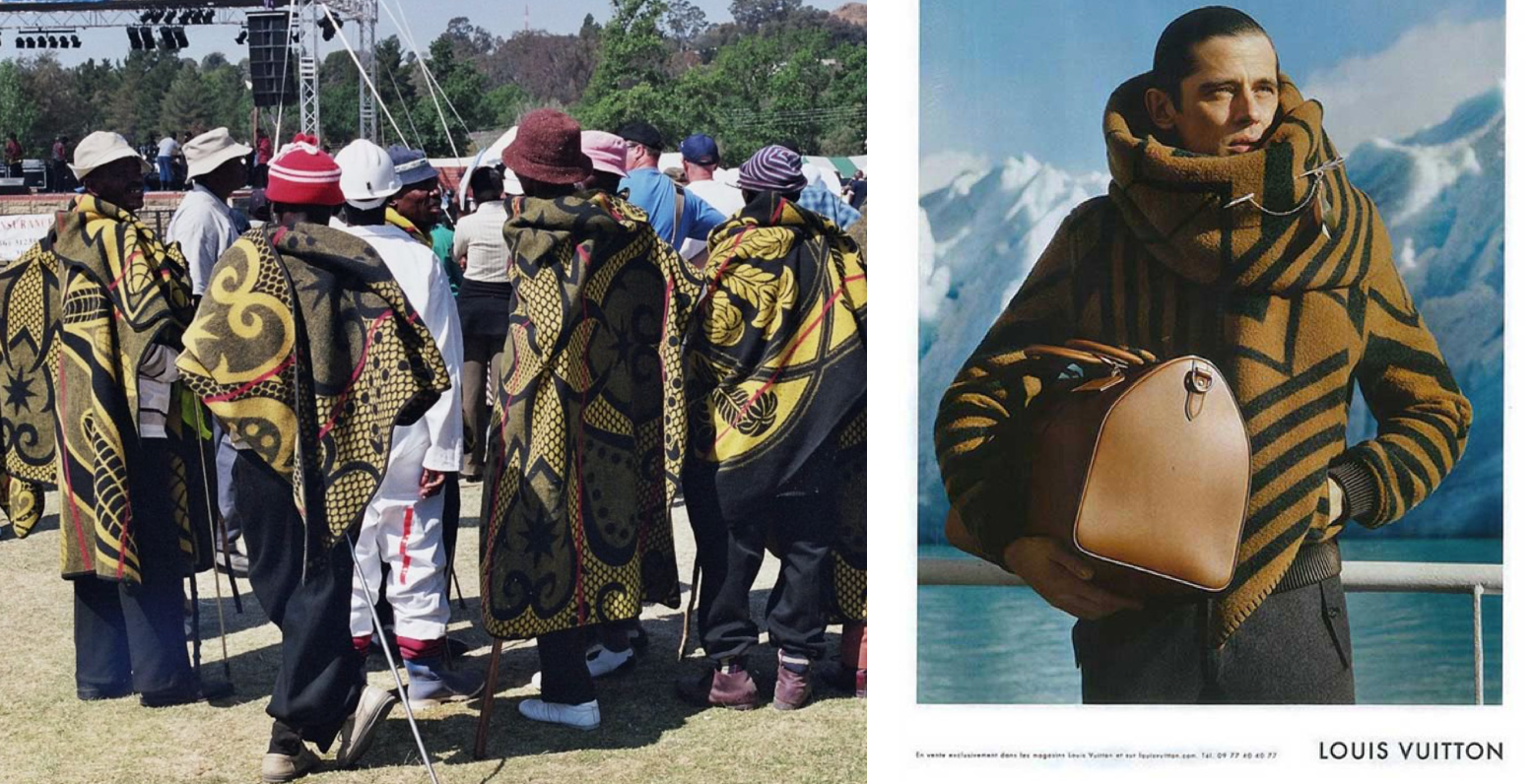

Louis Vuitton has also been called out for looking to others’ cultures for “inspiration.” On the heels of its Fall/Winter 2012 menswear show, Louis Vuitton was met with criticism from South Africans for allegedly turning the culturally significant Basotho blanket into a fashion trend for men. The Basotho – a Bantu ethnic group whose ancestors have lived in southern Africa since around the fifth century – say the blanket signifies a sacred ritual and normally does not go for more the R1,000 ($77) much less than the Louis Vuitton hefty price tag of R33, 000 ($2,553).

“We are angry because we feel exploited. It’s not just that they are inspired by us. That’s a compliment, but you need to take it a bit further and involve us, otherwise it is theft,” says well-known South African designer Maria McCloy.

“African artists are also artists and designers. We also have names. It is not just something blank that everyone has the right to come and take,” further stated.

UPDATED (7/19/2017): Louis Vuitton has subsequently been met with additional push back, as a more recent menswear range features a small cashmere and wool version of the Basotho blanket.

According to City Press, a blanket and shirt from Louis Vuitton Spring/Summer 2017 collection “references a blue and yellow version of a traditional Seanamarena design, with an exaggerated graphic maize cob and giraffe dominating the pattern. The Louis Vuitton products at issue also include the yellow ‘wearing stripes’ which traditionally designate the direction a blanket should be worn.”

Chere Mongangane, the co-founder of Bonono Merchants in Lesotho, a design collective aimed at putting the country’s fashion design capabilities on the map, said Louis Vuitton failed to make its products look any different from those being offered by Aranda Textiles, which produces the Basotho blankets.

According to Mongangane, “The person who made the blanket such an important cultural item is the founder of the Basotho nation, King Moshoeshoe I, and because of his heroic status among his people, every Mosotho wanted to own one. In the early years, it was a ceremonial garment worn mainly by the local chiefs and rich families around Lesotho, as it was not as accessible as it is today.”

“Fast forward to 2017 and Louis Vuitton has a range that does not say anything about Basotho beside mentioning the name –that’s the obvious problem. It is appropriating a culture, but isn’t willing to tell their story,” he said.

Despite the price tag and the backlash, the blankets have sold out, representatives for Louis Vuitton told City Press, in the brand’s Johannesburg and Cape Town locations. “The sad part of the situation, for me, is that the African consumer would rather consume the Louis Vuitton version than support small businesses who are already offering the same products,” said designer Thabo Makheta this week.

She continued on to note, “The downside is, of course, they are making a profit out of it. But at the same time, they sold out at the Johannesburg and Cape Town stores. As much as people are quite upset about what has happened, there are still people who are consuming those goods.”