Virtual goods – including those tied to non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) – may be capable of infringing others’ trademarks for purely “real” world goods. That is what a New York federal court indicated in a memorandum order last month, in which it refused to toss out the trademark infringement and dilution lawsuit that Hermès lodged against Mason Rothschild, the maker of the MetaBirkins NFTs. Denying Rothschild’s motion to dismiss, Judge Jed Rakoff of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York held that while there may be an “artistic aspect” to the images tied to the MetaBirkins NFTs (making the Rogers test applicable), Hermès has, nonetheless, sufficiently set out allegations that Rothschild’s use of “MetaBirkins” was not artistically relevant or was explicitly misleading.

Rothschild had pushed for a dismissal of Hermès’ lawsuit on the basis that his “fanciful depictions of fur-covered Birkin bags and his identification of his artworks as ‘MetaBirkins’ are artistically relevant and do not explicitly mislead about their source or content,” and thus, are protected as artistic expression under the First Amendment.

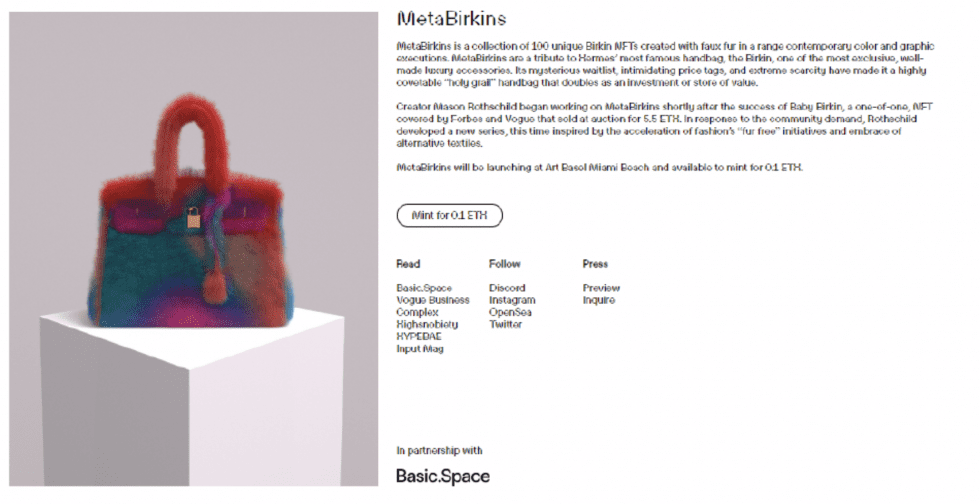

Among the key takeaways from the latest round of the closely-watched MetaBirkins lawsuit – which is one of the very first trademark matters to center on NFTs – is how the court construed NFTs. Relying largely on what Hermès sets out in its amended complaint, the court describes NFTs as “units of data stored on a blockchain that are created to transfer ownership of either physical things or digital media.” When an NFT is linked to digital media, the court states that “the NFT and corresponding smart contract are stored on the blockchain and are linked to digital media files (e.g., JPEG images, .mp4 video files, or .mp3 music files) to create a uniquely identifiable digital media file.”

Meanwhile, the court noted that “the digital media files to which the NFTs point are stored” – and ultimately, exist – “separately” from the digital tokens, themselves.

In this same vein, Judge Rakoff stated that “because NFTs are simply code pointing to where a digital image is located and authenticating [that] image, using NFTs to authenticate an image and allow for tradeable subsequent resale and transfer” does not make the image tied to an NFT a commodity cut off from potential First Amendment protection “any more than selling numbered copies of physical paintings would make [them] commodities for the purposes of Rogers.”

The court goes further in its discussion of the fundamentals of NFTs (and the different types of assets that can be tied to NFTs), asserting in a footnote that “an NFT could link to a digital media file that is just an image of a handbag” – as is the case here. Alternatively, the judge suggests that an NFT could be associated with “a different kind of digital media file that is a virtual handbag that can be worn in a virtual world,” such as a metaverse platform. This distinction is significant, as it seems to clearly indicate that not all digital images linked to NFTs would invoke the Rogers test. (Under Rogers, the unauthorized use of another’s trademark in an expressive work is shielded from liability under the Lanham Act unless it “has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever” or has “some artistic relevance, [but] explicitly misleads as to the source or content of the work.”)

While some allegedly infringing works – such as the MetaBirkins images – that are linked to NFTs might warrant an analysis under Rogers because of their expressive nature, Cowan, Liebowitz & Latman’s Eric Shimanoff noted recently that “a traditional trademark analysis might apply if, for example, the MetaBirkins were sold as virtually wearable goods for use in the metaverse, thus, making them more akin to commodities as opposed to artistic works.”

In a separate footnote, the court asserts that Rothschild “seems to concede” that Rogers “might not apply if the NFTs were attached to a digital file of a virtually wearable Birkin, in which case the ‘MetaBirkins’ mark would refer to a non-speech commercial product.” That is, of course, not at play here since the 100-or-so MetaBirkins consist of static images, and the court does not delve further into this, stating that Hermès’ only contention on this front is that “Rothschild might branch out into virtually wearable ‘MetaBirkins.’” Since the amended complaint does not contain “sufficient factual allegations that Rothschild uses, or will in the immediate future use, the mark to sell such products,” the court did not consider this in connection with the motion to dismiss.

The court’s discussion of what an NFT actually consists of is noteworthy, as it is one of the critical – and largely untested – questions in a number of lawsuits, including the one that Nike has filed against StockX over its sale of NFTs. It also sheds light on the potential for courts to distinguish between the types of media that can be tied to NFTs, which brands and creators should take note of.

Beyond that, the court’s order seems to suggest that the trademark rights that brands have amassed for use on purely physical goods (and “real” world services) could very well extend into the metaverse and allow for infringement claims in the event that the assets tied to the NFTs – or potentially, just virtual goods themselves that are not tied to NFTs at all – are capable of functioning in the metaverse. Hermès, after all, has yet to make use of the protected Birkin name or trade dress in connection with any virtual products or NFTs, but that seemingly does not stop its existing “real” world rights from extending into the virtual world. (It likely helps, as Hermès has argued – and the court notes in its order – that many other similarly-situated brands are beginning to “branch out into offering virtual fashion items that can be worn in virtual worlds online (most commonly, for now, in the context of video games, but with the potential to expand into other virtual worlds and platforms as those develop), and NFTs can be used to create and sell such virtual fashion items.”)

This takeaway comes as no shortage of brands have lodged metaverse and/or NFT-focused trademark applications for registration (often on a 1(b) basis) with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) and other international trademark offices for marks that they currently use exclusively on goods/services in the “real” world. These applications largely list classes 9, 35, 41, and 42 as among those in which brands intend to use the marks. As TFL previously reported, brands appear to be “hedging” by way of the disparate classes they are filing for, which is an illustration that they are “not quite sure what they are going to do in the metaverse or how the USPTO is going to treat their applications.”

However, at the end of the day, as Martin Schwimmer, a partner in the Trademark and Copyright Practice Group at Leason Ellis, told TFL, with regards to “a company’s main line of work,” a company’s “existing trademark portfolio will probably cover the most predictable of their activities in the metaverse.”

The case is Hermès International, et al. v. Mason Rothschild, 1:22-cv-00384 (SDNY).