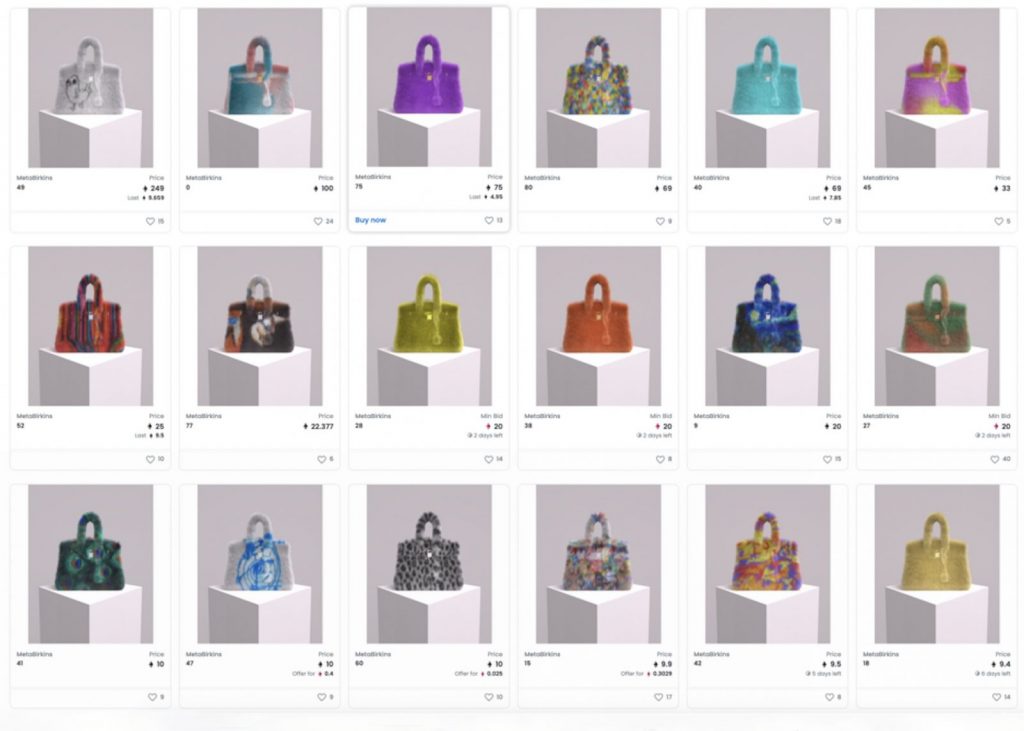

Brooks Sports’ and Skechers have settled a trademark clash over their uses of the “BEAST” mark in connection with running sneakers. In a notice of voluntary dismissal on Wednesday, as first reported by TFL, Brooks alerted the court that the parties have reached a settlement and accordingly, it is voluntarily dismissing its trademark infringement, false designation of origin, and unfair competition claims against its fellow footwear maker with prejudice. The terms of the parties’ resolution have not been disclosed, as of the time of publication, but Skechers’ website is devoid of any sneaker styles bearing the “BEAST” mark, suggesting that it will refrain from using the mark as part of the deal.

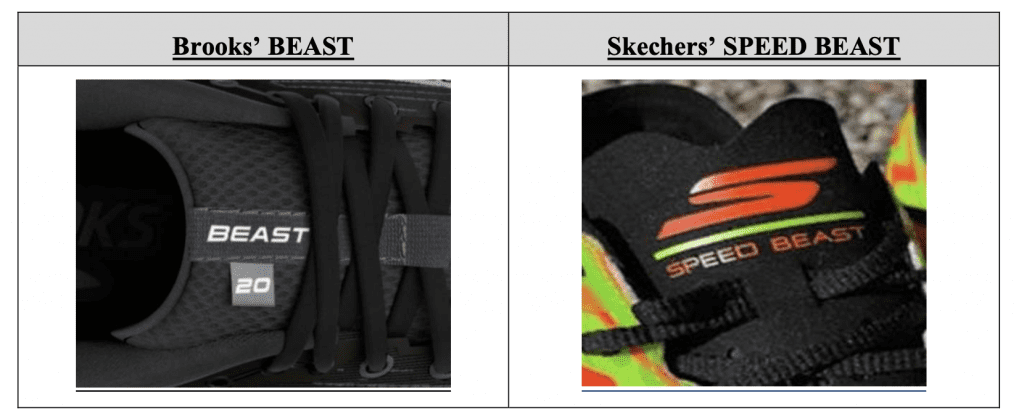

The short-lived lawsuit got its start when Brooks filed its complaint in April 2023, telling the court that it was looking to “stop Skechers from using [its] BEAST trademark on running shoes and to prevent the resulting public confusion and damage to Brooks” as a result of such use. One of its “most enduring models” is the BEAST sneaker, which it has sold in various iterations for more than three decades, Brooks asserted. In a bid to piggyback on the appeal of the Brooks brands and its offerings, it claimed that “Skechers’ recently-released SPEED BEAST shoe irreparably harms [its own] BEAST brand and causes consumer confusion.”

The tension between the brands as Skechers is not limited to this case: the parties faced off in a separate – and since-settled – trademark fight last year when Skechers accused Brooks of infringing – and diluting – its “famous ‘S’ logo” by using a “confusingly similar ‘5’ mark” on footwear. Skechers alleged that the stylized number “5” that appeared (and still appears) on Brooks’ sneakers is “substantially identical to many of Skechers’ ‘S’ marks and is used on similar products marketed to the same consumers, making it highly likely that consumers will be confused as to whether Skechers is responsible for, distributes, has authorized or licensed, or is otherwise involved with the shoes Brooks sells.”

(In the case at hand, Brooks argued that “Skechers’ appropriation of [its] rights in the BEAST mark was no accident,” as in the immediate wake of the “S”-centric trademark lawsuit, which saw Skechers “carefully review Brooks’ product line,” the Southern California-based brand released its SPEED BEAST running shoe, “intending to capitalize on the goodwill of one of Brooks’ staple products – the BEAST.”)

Competition-Driven Claims

Bigger than a battle over “BEAST,” the Brooks-initiated lawsuit appears to be just as much a clash over competition amid an effort by Skechers to branch out from “comfort, ‘family’ footwear” into more serious athletic sneakers, which is 109-year-old Brooks’ main market. Berkshire Hathaway-owned Brooks argued in its complaint that “Skechers cannot use [its] well-known BEAST trademark to pivot its brand in order to attract serious athletes.” By offering up a sneaker adorned with the word “BEAST,” Brooks argued that Skechers “seeks to ride the coattails of Brooks and profit from Brooks long-standing trademark, BEAST, and Brooks’ hard-earned reputation for building premium products for runners.”

The most telling language in the “BEAST” case is, of course, Brooks’s assertion that “the parties’ running shoes are directly competitive with each other, sold to the same customers through the same trade channels, and marketed through the same marketing channels.” In other words, Skechers’ new performance offerings – which it introduced in order to take a piece of the running sneaker market, one that is expected to reach almost $75 billion in value by 2031 – hit a bit too close to home compared to its previous offerings (think: chunky white walking sneakers and fashion-inspired wares) and thus, were likely to confuse consumers.

If this case and others – including the trademark suit that adidas waged against Thom Browne – are any indication, as brands make inroads into new areas of the market or even, as is the case here, new corners of the same larger market segment, trademark squabbles between players that previously co-existed are likely to follow. Part of the key to successfully escaping such suits? Establishing that despite expansion efforts, the companies and their wares still occupy distinct parts of the market with different sets of consumers – as evidenced, in part, by vastly different price points – worked for Thom Browne.

The case is Brooks Sports, Inc. v. Shechers USA, Inc., 2:23-cv-00598 (W.D. Wash.).