Chanel is shedding additional light on its stance on others’ use of its trademarks in a lawsuit over jewelry crafted from buttons bearing its famed interlocking “C” logo. In the complaint that it filed with the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York on August 2, Chanel alleges that jewelry brand Villo & Co. and its owner Neely Mullins (collectively, the “defendants”) are on the hook for trademark infringement, dilution, counterfeiting, false association, and false advertising as a result of “their ongoing, unauthorized misappropriation of Chanel’s iconic CHANEL and interlocking CC Monogram trademarks in connection with their creation and sale of costume jewelry.”

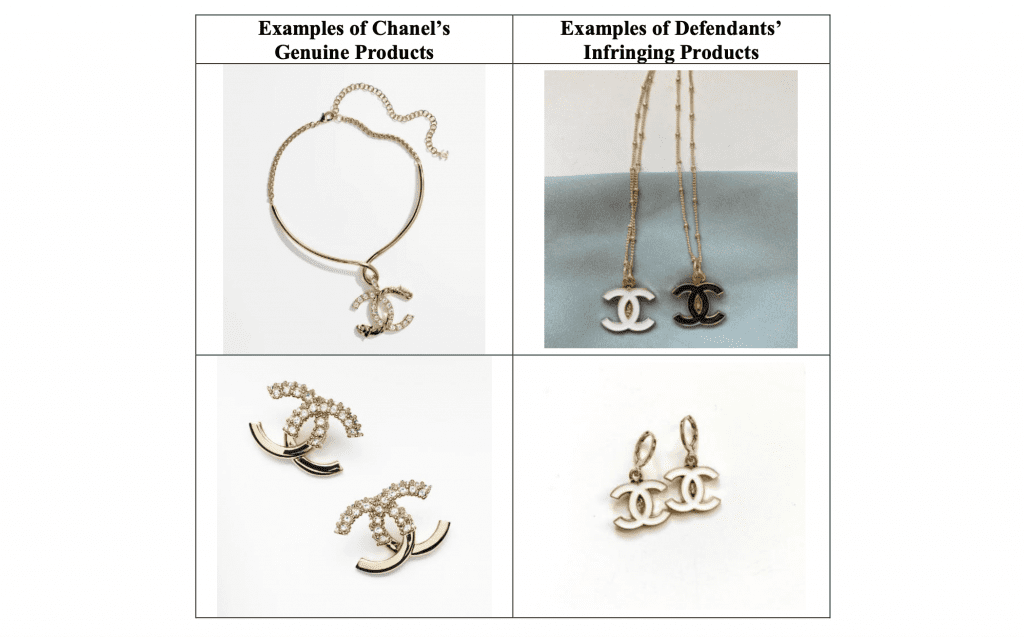

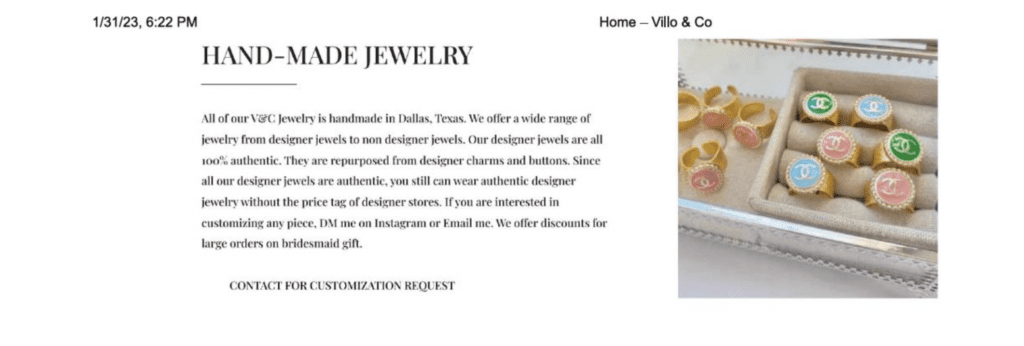

Setting the stage in the newly-filed lawsuit, Chanel claims that the defendants have taken buttons and other items bearing CHANEL trademarks and incorporated them into chains, earrings, and other jewelry items that are advertised and sold as “authentic” “designer” jewelry. From a product perspective, Chanel takes issue with the defendants’ use of: (1) seemingly straightforward counterfeit materials, namely, Chanel trademark-bearing items that it claims were “actually never used in genuine Chanel products” and that were obtained from “unknown third parties, which include counterfeiters,” and (2) trademark-emblazoned materials, such as buttons, that were potentially derived from authentic Chanel products.

The latter is the especially interesting aspect of the lawsuit, as while some of the logo-bearing buttons and other materials may have originally come from authentic Chanel products (and could – in theory – fall within the bounds of the first sale doctrine), Chanel contends that the defendants are still in the wrong because they: (1) have engaged in false advertising in connection with the “repurposed” jewelry products; and (2) are using those potentially authentic Chanel materials in ways that were “not intended or authorized for use by [them].”

100% Authentic?

First things first, in addition to trademark infringement and dilution claims, Chanel sets out false advertising and false association causes of action that stem largely from the defendants’ alleged practice of characterizing their jewelry as “100% authentic” and “designer” goods in “an attempt to deceive consumers into believing that their products are somehow associated or affiliated with Chanel or that parts of the products are directly obtained from Chanel.” There is no association between the parties here, per Chanel, as “none of the defendants’ products or component parts … are authenticated by Chanel, endorsed by Chanel, or at all associated with Chanel.”

In fact, Chanel states that it “has not authorized or approved [the defendants’] authentication of secondhand Chanel products as genuine.” And on the authentication front, in particular, while the defendants market the goods as “100% authentic,” Chanel alleges that they “do not have any process by which they may accurately verify and guarantee the authenticity of the products bearing the CHANEL marks, or component parts bearing the marks,” and it is “not involved in authenticating or approving any products sold by the defendants and does not offer any guarantee to consumers that any products sold by the defendants are authentic or approved by Chanel.”

If any of this sounds familiar, it may be because Chanel has made somewhat similar claims in its cases against The ReaReal (“TRR”) and other resellers, namely, in response to their sale of a mix of allegedly infringing/counterfeit and potentially authentic goods and their authentication-specific advertising of those goods. You may recall that Chanel filed suit against TRR back in 2018, accusing the reseller of offering up counterfeit goods, while also “represent[ing] to consumers that it ‘ensure[s] that every item on TRR is 100% the real thing thanks to our dedicated team of authentication experts.’” (Chanel has similarly taken issue with TRR’s authentication practices, arguing that none of its authenticators “have been trained by Chanel in the ways to properly authenticate a genuine Chanel product,” and “only products purchased directly from Chanel and its authorized retailers can be certain to be” – and thus, be advertised as – “genuine and authentic.”)

Around the same time, Chanel also filed suit against What Goes Around Comes Around for trademark infringement and false association over the resale company’s advertising and sale of Chanel-branded goods that allegedly “violate Chanel’s trademarks and improperly trade off [its] brand in order to create the false perception that WGACA is affiliated with Chanel.”

Both of those cases are still underway.

It is worth noting that beyond the defendants’ authenticity-specific claims, Chanel’s false advertising claims also center on their practice of referring to their offerings as “designer,” an issue that is not present in any of the resale cases (to my knowledge).

Unintended Use, Component Parts

Chanel also argues that the defendants’ use of even potentially authentic trademark-bearing “buttons and components” to create their own jewelry and accessories is problematic, as they are using these branded materials “as the featured element of [their] products” – which is something that Chanel says it “did not intend” when it released button-bearing products into the market. Chances are, Chanel is waging this claim in an attempt to get out ahead of any first sale doctrine-centric arguments from the defendants. After all, while parties commonly point to the first sale doctrine when reselling genuine trademark-bearing items in their entirety, they may also escape liability for their subsequent sale of trademark-bearing components of a larger product.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, for one, held last year in Bluetooth Sig Inc. v. FCA US LLC (citing SCOTUS’s 1925 decision in Prestonettes, Inc. v. Coty, and its own 1998 holding in Enesco Corp. v. Price/Costco) that the doctrine applies to the inclusion of component parts in new, downstream products. There are limits, and as the court held in Bluetooth, a first sale defense applies “in instances in which a trademarked product or a component is incorporated into a new end product so long as the seller adequately discloses to the public how the trademark product was used or modified in the new product.”

The ability for parties to rely on the first sale doctrine when they have used parts of a plaintiff’s product may not prove to be a home run for the defendants here due to their alleged failure to make the necessary disclosures. According to Chanel, the defendants – which claim that their “designer jewels are all 100% authentic” and are “repurposed from designer charms and buttons” – have not disclosed that “the jewelry is created without the authorization of Chanel or that the items are not authenticated by Chanel,” thereby, giving rise to potential confusion. This is especially likely since Chanel asserts that “there is no distinguishable difference between the appearance of the defendants’ infringing products and [its own] genuine products.”

With all of the foregoing in mind, Chanel claims that the defendants’ conduct has caused and continues to “immediate and irreparable injury” to its brand, and is seeking monetary damages and injunctive relief to permanently bar them from using the trademarks at issue in connection with the promotion or sale of any goods or services; marketing its goods in a manner that causes consumers to believe that they are associated or affiliated with Chanel in any way or that their goods “have been approved or authenticated by Chanel or individuals affiliated with Chanel;” and disseminating any false and/or misleading information relating to the “authenticity, nature, or origin of their goods” with respect to Chanel, among other things.

The case is Chanel, Inc. v. Villo & Co., LLC, et al., 1:23-cv-06781 (SDNY).