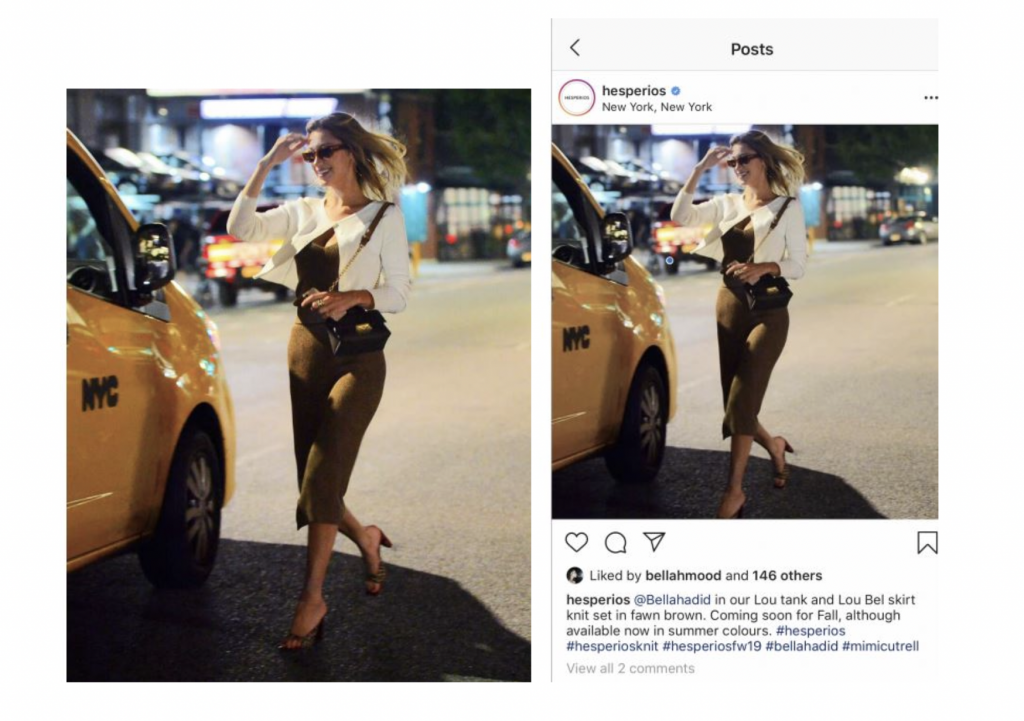

A photo of Bella Hadid was at the center of a fashion brand’s recent bid to escape copyright infringement liability. On the heels of being sued by paparazzi photographer Jawad Elatab in October 2019 for posting a photo that he took of the supermodel on Instagram to promote its brand without licensing the photo or otherwise receiving Mr. Elatab’s authorization, Hesperios argued that the case should be tossed out of court because its use of the image – along with the caption “@Bellahadid in our Lou tank and Lou Bel skirt knit set in fawn brown. Coming soon for Fall, although available now in summer colors” – amounts to fair use or at least de minimis use because of the “negligible amount time” for which it appeared on the brand’s Instagram story.

In an order early this month, Judge Andrew Carter of the U.S. District Court of the Southern District of New York, sided with the photographer, in part, and the New York-based brand. First addressing Hesperios’s fair use argument, Judge Carter pointed to four nonexclusive factors that inform whether a given use is fair: “(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” Beyond that, he stated that while courts have, in fact, “granted motions to dismiss infringement claims based on a defendant’s fair use defense … as this Court has previously observed, ‘there is a dearth of cases granting such a motion.’”

Against this background, Judge Carter looked to the purpose/character of Hesperios’s use of the photo of Hadid, noting that the fashion brand argued that its use of the image was transformative (and thus, fair) because it “created the clothes that the model was wearing, and [its] purpose in posting the image was to invite its Instagram followers to provide commentary on the photograph.” The court did not buy that argument, saying that Hesperios did not make “any modifications” to the photo before it posted it, and instead, opted to include “a description of what the model was wearing, as well as when the item would be available.” Beyond that, Judge Carter stated in his memo and order that “nowhere in [Hesperios’s] posting of the image does [it] invite its Instagram followers to provide commentary,” not does it “provide its own critique of the image.”

“While commentary and critique have been considered fair use,” the court stated, that is not what is going on here, and “the court cannot credit [Hesperios’s] assertion that its posting of the photo alters the original message of the photograph.”

Also on the purpose/character front, Judge Carter says that Hesperios failed to successfully make its argument, as it “posted the photograph on Instagram as marketing to promote their brand,” a fact that is bolstered, according to the court, by Hesperios’s PR company pushing it to post the image online, and to “send [it] to potential wholesale clients as well,” a “subfactor” that the court says “counts against finding fair use as [Hesperios]has failed to demonstrate that its post was anything other than commercial use to advertise its clothing.

In terms of the nature of the work, the court cited its determination in an earlier case, one that fashion photographer Mark Iantosca filed against Elie Tahari, in which it held that “a photograph of a model, is a typical ‘creative’ work and therefore entitled to copyright protection,” again, siding with Elatab.

Looking to the amount and substantiality of the original work that was used by Hesperios, the court stated that “this factor weighs against a finding of fair use,” as well, as Hesperios used the entirety of Elatab’s image, and the court was not persuaded by its argument that “the full use of the photograph was required because the purpose of the photograph was to invite its members to comment.” Judge Carter says that such a claim “is bellied by the actual Instagram post in which [Hesperios] advertises its clothes that are being worn by the model in the photograph and provides it viewers with when it will be available.”

The final factor, which considers the potential competitive effect that Hesperios’s allegedly infringing use of the photo has on the market for Elatab’s original photo, also weighs against a fair use finding, as Hesperios’s “posting of the photograph to promote its clothing certainly has the potential to supplant the market for [Elatab] to license the photograph.” Having found that Hesperios failed to make sufficient arguments for each of the fair use factors, the court denied Hesperios’s motion to dismiss.

With fair use out of the way, the judge turned his attention to Hesperios’s argument that “its singular posting of the photograph for a negligible amount time was de minimis and thus the complaint must be dismissed for failure to state a cause of action,” which he similarly shot down on the basis that “because [Hesperios] has used the photograph in its entirety, [it] cannot claim that [its] use was de minimis.” Still yet, the court refused to dismiss Elatab’s copyright infringement claim, stating that he has a valid copyright in the image and that Hesperios posted it on Instagram without his authorization, thereby, engaging in infringing activity.

The one place where Hesperios did nab a win in this round was in regards to willfulness, as it successfully argued that Elatab failed to adequately allege that its infringement of the photo was willful, and thus, that he is entitled to an enhanced award of statutory damages. Judge Carter did, however, grant allow Elatab a chance to amend his complaint to adequately allege willfulness, also stating that he “encourages the parties to discuss settlement.”

The case that Elatab filed against Hesperios falls neatly within a sizable number of cases that paparazzi photographers have filed against celebrities, models, and fashion brands over the past several years for posting photos – most often of themselves and/or of their designs – on Instagram without licensing the imagery in an aim to market the products or themselves on social media.

The case is Jawad Elatab v. Hesperios, Inc., 1:19-cv-9678 (SDNY).