UPDATE (July 14, 2022): Since this article was published, TFL spoke with the plaintiffs’ attorney Edward Greenberg, who stated that all he could reveal is that the parties “amicably settled the action.”

A group of nearly 50 runway models are voluntarily dismissing their claims against Condé Nast in the almost two-year-old lawsuit that they filed against it and e-commerce retailer Moda Operandi. After settling out of court, counsel for Abby Champion and dozens of other big-name models – who have appeared in dozens of ad campaigns and walked in runway shows for the likes of Chanel, Dior, Louis Vuitton, Versace, Prada, and Lanvin, among other big-name brands – and counsel for the Vogue publisher alerted a New York federal judge in a stipulation of dismissal that they are looking to dismiss their respective claims with prejudice and without costs or fees for either party, as first reported by TFL.

The July 8 stipulation will serve to dismiss the models’ only remaining claims against Condé. These consist of an array of right of publicity claims (under New York Civil Rights Law s. 50 and 51), as the federal false designation of origin claims that they filed against the New York-headquartered publisher were dismissed by the court last year. It will also see Condé voluntarily drop the anti-SLAPP counterclaim that it lodged in November 2021 in response to the suit.

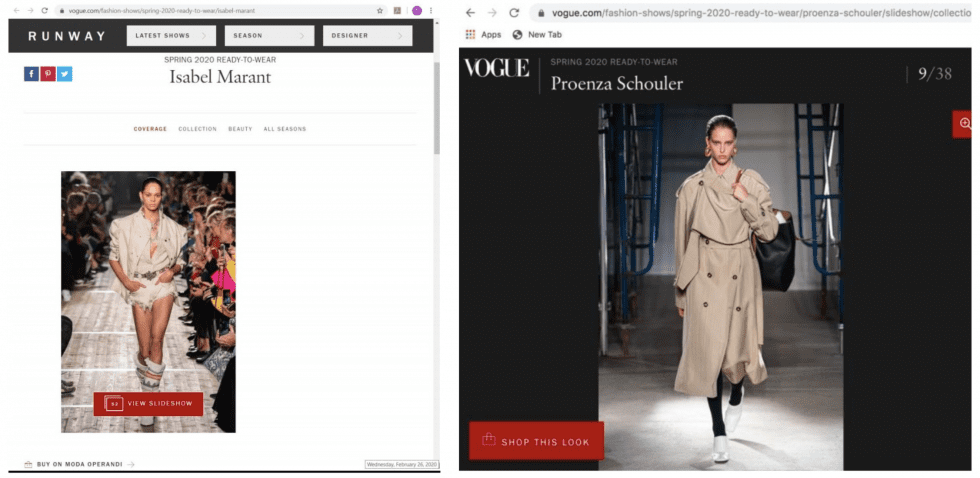

Dozens of Next Management-represented models first filed their lawsuit against Condé Nast and Moda Operandi in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York in September 2020, alleging that in furtherance of a commercial arrangement, the defendants used photos and videos of them walking in seasonal runway shows in order to “steer traffic” to Moda Operandi’s e-commerce site, where consumers can then purchase the specific runway looks, all without “seek[ing] or obtain[ing] their prior written consent,” thereby, engaging in false designation of origin and violating New York’s right of publicity law.

In furtherance of their false designation of origin claims, the models alleged that they are “routinely hired by companies for their modeling services to sell products,” and thus, when Condé Nast and Moda Operandi include links that enable consumers to “Shop This Look” next to images of them on the runway, “the general public is likely to be, and has been, deceived and/or confused into thinking that the plaintiffs have provided their respective sponsorship or approval to the services offered by Moda and Vogue.” Beyond that, they have also alleged that Condé and Moda’s unauthorized use of their images and likeness flies in the face of New York right of publicity law, which prohibits the unauthorized commercial use of another’s name, portrait or picture.

In response to the lawsuit, Condé Nast and Moda argued that the models failed to make their case for a number of reasons, including because Condé’s use of the photos is protected by the First Amendment, and given that “Moda’s typical consumers” will understand the use of the images not meant “to imply source, sponsorship, or endorsement of Moda or its products,” they will not believe that the models are endorsing or associated with it.

Judge Colleen McMahon agreed with the defendants, in part, dismissing all of the models’ false endorsement claims against Condé, more than a dozen of their false endorsement claims against Moda Operandi, and most of their right of publicity claims against both defendants in an order in September 2021. In that order, Judge McMahon stated that a number of the models had engaged in “a blatant effort to federalize a state [right of publicity] law claim and extend its reach to individuals who have no rights under this state’s law.” The judge asserted that “the mere fact that a majority of [the plaintiffs’] modeling work takes place in New York is not sufficient to establish domicile, when [they] reside elsewhere.”

The judge also took issue with the models’ false endorsement claims, stating in her order that “Vogue’s Runway [vertical] is an expressive work” and its “use of the plaintiffs’ images is artistically relevant.” There is “no question that Vogue’s use of the photos, taken on the runway, in a summary document about the season’s new fashions intends an ‘artistic’ and non- commercial purpose,” the court stated, noting that Vogue’s use of the photos does not “explicitly mislead as to the source or content of the work.” As such, Condé’s use of the imagery “easily falls within the safe harbor of the Rogers test.”

With Condé out of the picture, Moda Operandi is the sole defendant, and it is facing more than half of the models’ false endorsement claims, which Judge McMahon kept intact in her September 2021 order. (In her order, the judge stated that “there is no question of journalism or application of the Rogers test to Moda’s use of the plaintiffs’ photos,” as the retailer “displayed the runway pictures on its website for one reason only: to show off clothing it had for sale.” Despite keeping 25 of the the models’ false endorsement claims against Moda in place, Judge McMahon, nonetheless, said that she is still not convinced that they will ultimately prevail, pointing to the sophistication of Moda audience, for instance, as weighing in its favor. It is “unlikely that individuals who can afford to” – or are in the habit of “purchas[ing] designer clothing and who follow fashion design would be easily misled about what it was that the plaintiff models were, and were not, doing.”)

Reflecting on some key takeaways from the case in November, Reed Smith LLP’s Stacy Marcus, Deborah Bessner and Jenny Waxman stated in a note that “not all states protect a right of publicity and attempts to gain a backdoor entry to state law protections will likely not work,” noting that “this will limit the pool of potential plaintiffs bringing right of publicity claims and lessen a brand’s exposure based on where talent resides.” At the same time, they assert that it is worth keeping in mind that “an expressive work need not be exclusively expressive to garner constitutional protections, [as] if a brand creates work that has both commercial and expressive aspects to it, the company may still be protected from false endorsement liability if the purpose of the work, as a whole, is expressive.”

*This article was initially published on July 12, and has been updated with a comment from the plaintiffs’ counsel.

The case is Champion et al., v. Moda Operandi, Advance Publications d/b/a/ Conde Nast, 1:20-cv-07255 (SDNY).