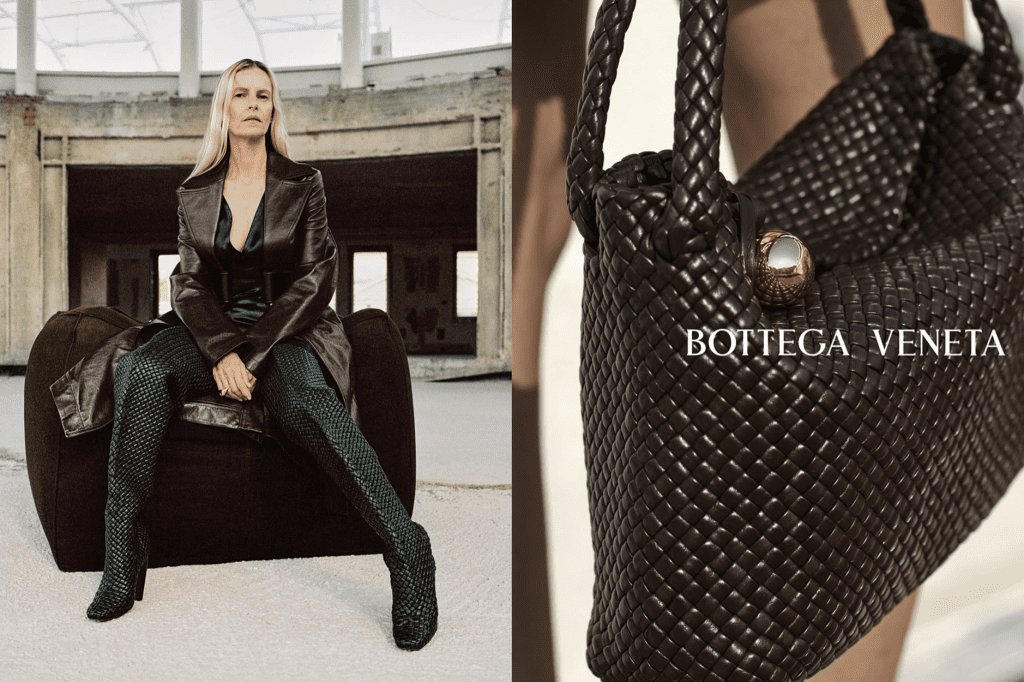

Something interesting appears to be underway at Bottega Veneta. In the wake of former creative director Daniel Lee’s tenure, which was dominated by millennial-focused “it” accessories, many of which featured an exaggerated take on the brand’s intrecciato weaving technique, a largescale return to Bottega Veneta’s classic woven pattern may be making a comeback. One need not look further than new creative chief Matthieu Blazy’s debut ad campaign for the Kering-owned company to see that he might be forging his path at Milan-based Bottega Veneta by bringing the traditional intrecciato pattern back to the fore; the well-known design can be found adorning an array of handbags and some stand-out over-the-knee boots in the ad campaign that the Milan-based brand released this summer.

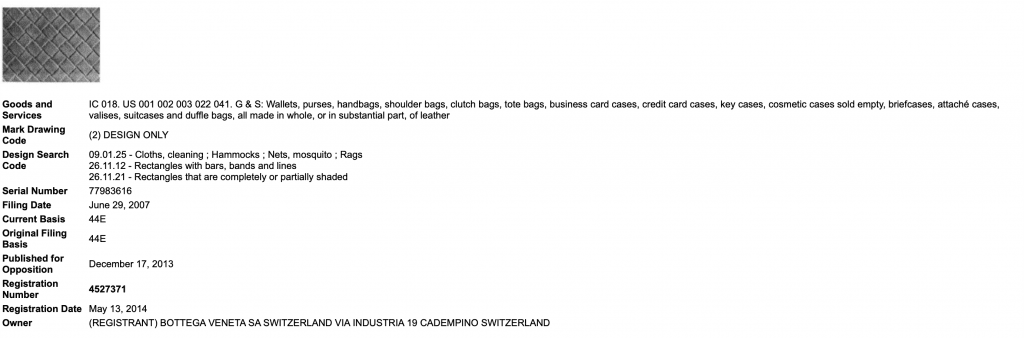

The potential re-popularization of the traditional intrecciato weave is a notable one, as it comes with a backstory about the nature of the design and the brand’s trademark rights in it. The matter dates back to 2007 when counsel for Bottega Veneta filed an application to register the appearance of the weave with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) for use on leather handbags (as well as wallets, card cases, etc.) (in Class 18) and footwear (Class 25). In the end, Bottega was awarded a registration for the mark for use on handbags (Reg. No., 4527371), but only after a protracted back-and-forth between its legal counsel and the USPTO and then the USPTO’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (“TTAB”) in the wake of a USPTO examiner refusing to green-light registration of the mark on the basis that it was aesthetically functional and merely ornamental.

According to the USPTO examiner, in addition to the weave being viewed by consumers primarily as a decorative feature of Bottega’s bags (instead of as an indicator of their origin), the inability of other brands to use the woven pattern without engaging in infringement of Bottega’s rights would put them at a competitive disadvantage. Against that background, the USPTO lodged a final refusal.

Unhappy with the outcome, Bottega appealed to the TTAB, which ultimately reversed the aesthetic functionality and ornamentality refusals in September 2013, and held that the Italian luxury goods brand’s mark – which consists of “a configuration of slim, uniformly sized strips of leather, ranging from 8 to 12 millimeters in width, interlaced to form a repeating plain or basket-weave pattern placed at a 45-degree angle over all or substantially all of the goods” – could be registered for use on various types of leather bags. (The original application was divided to create two separate applications, one for handbags and one for footwear, and the latter (Ser. No. 77219184) was shut down by the TTAB in 2019.)

Deciding the appeal over the intrecciato mark for use on handbags in 2013, the TTAB determined that a registration for Bottega would not deprive competitors from using a woven leather design for handbags of their own as long as the weave pattern is not “an identical or nearly identical design” to the one described on Bottega’s registration. In addition to overcoming the USPTO’s aesthetic functionality argument, Bottega also beat the ornamentally issue, establishing that the weave had acquired the necessary distinctiveness in the minds of consumers to indicate their source. It did so by presenting evidence of extensive use of the mark beginning in 1975, advertising expenditures (between 2005 and 2009 Bottega spent over $22.9 million advertising products bearing its weave design in the U.S.), and sales (between 2001 and 2007, Bottega generated U.S. sales of more than $275 million, with the weave design appearing on over 80 percent of its goods), among other things.

Scope & Strength of the Mark

The back-and-forth between Bottega and the trademark bodies made for one of the most intriguing trademark prosecutions in fashion at the time and a notable win for Bottega. But fast forward to 2022 to what appears like it could be the beginning of a big push to put intrecciato weave accessories at the center of the brand, and it is not exactly clear how strong the brand’s rights in the weave actually are. It is well-established that the scope of protection for the intrecciato is limited: The configuration elucidated in Bottega’s registration is narrowly construed – down to the millimeter, and the TTAB even said so much, asserting in its 2013 opinion that the weave is not aesthetically functional “based on a very narrow reading of the proposed mark, and the scope of protection to which it is entitled.” The TTAB also noted that a registration for the mark would not be an issue from an esthetic functionality standpoint because Bottega’s rights only extend to “identical or nearly identical design[s] comprising the elements listed in the description of [its] mark.”

Looking beyond the scope of the registration, which appears to leave quite a bit of room for third parties to legally sell bags that bear patterns consisting of non-leather strips, thicker strips of leather, and/or a leather weave pattern positioned at different angles, the strength of Bottega’s intrecciato trademark is not necessarily obvious. After all, we have not seen the mark challenged in connection with litigation, for instance. In fact, Bottega does not appear to aggressively enforce its rights in the mark by way of infringement lawsuits in the U.S., despite potential infringements coming by way of handbags from other brands and a huge array of Amazon and Etsy sellers. The brand has filed trademark suits against counterfeit sellers and Alibaba, alike, in the past, but it does not appear to be in the business of filing regular enforcement-centric lawsuits in the U.S. like many of its peers do. (This could potentially provide infringers an opportunity to argue against the strength of Bottega’s mark.)

One place where we have seen some action testing the strength of the intrecciato weave mark is on the footwear front – albeit not from Bottega, but in the form of a successful opposition from footwear brand Marc Fisher, which sought to block the application filed by Bottega back in 2007 (Ser. No. 77219184) for the same intrecciato weave for use on footwear. Marc Fisher argued – and the TTAB agreed in June 2019 – that Bottega’s mark for use on footwear was merely ornamental and that the brand had failed to establish acquired distinctiveness.

As a takeaway point, the Marc Fisher opposition should serve as a lesson for brand owners involved in lengthy prosecutions. While Bottega had previously put forth a mountain of evidence of acquired distinctiveness for the weave pattern, which is what enabled it to amass a registration for the mark in Class 18, the TTAB refused to consider much of that evidence because it was at least ten years old by the time the board decided the Fisher opposition, a reminder that such evidence should be kept up to date. Based on the record as a whole, the TTAB concluded that Bottega had failed to overcome Marc Fisher’s prima facie case of lack of acquired distinctiveness, and sustained the opposition as a result, finding it unnecessary to reach Fisher’s claim of aesthetic functionality.