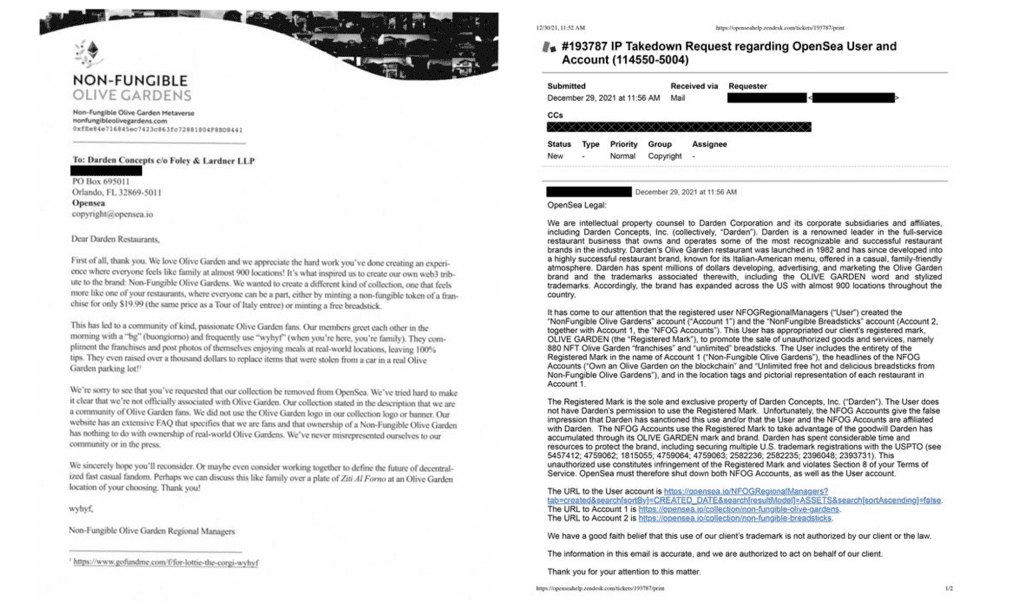

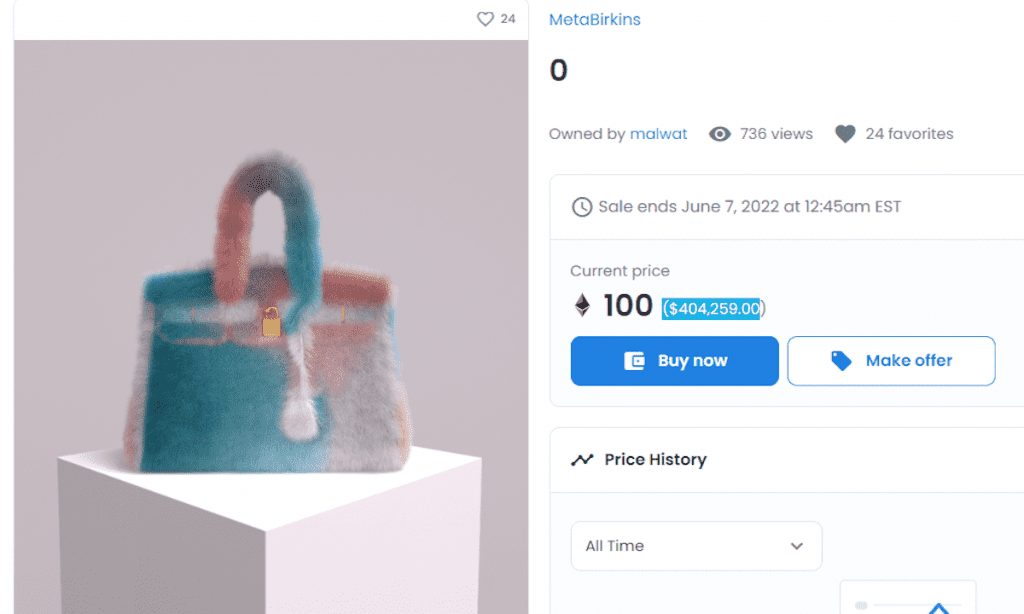

The battle between brands and unauthorized non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) has really started to bubble. Over the past few weeks, Hermès allegedly sent a cease-and-desist letter to the creator of the MetaBirkins and presumably filed a takedown notice with OpenSea to have the NFTs removed from the platform. Olive Garden owner Darden Restaurants lodged an IP Takedown Request with OpenSea to get NFTs linked to images of 880 physical outposts of the restaurant chain, which Darden claims violates its trademarks and OpenSea’s terms that prohibit infringement. Still yet, OpenSea recently banned some $2.2 million worth of PHAYC and Phunky Ape Yacht Club NFTs – both of which include mirrored images of the unrelated Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs – on copyright grounds.

Taken together, these individual instances shed light on some of the burgeoning legal issues that are beginning to pop up in connection with the metaverse (i.e., the virtual reality construct that marries reality with the online 3D virtual environment, and that enterprising brands and other entities are readily populating in order to connect with consumers and generate revenue). Many of the issues stem from the fact that while a growing number of the digital offerings that are being introduced on gaming platforms like Roblox and Fortnite, ecosystems like Decentraland and the Sandbox, and via NFT marketplaces are the result of collaborations with brands, many are not. Neither the creator of the headline-making MetaBirkins nor the anonymous group behind the Non-Fungible Olive Gardens received the respective trademark holder’s authorization to use these well-known marks, hence, the upheaval.

The law is relatively well-established when it comes to trademark clashes over tangible goods and corresponding services. For instance, the unauthorized use of Hermès’ name and/or its Birkin trademarks in a way that might confuse consumers, such as on physical handbags and related offerings, or that would not confuse consumers but that would otherwise damage the French luxury goods brand make for easy infringement and/or dilution claims for Hermès. The same can be said for Darden in the event that an unaffiliated third party started using the trademark-protected Olive Garden name in connection with physical restaurant operations or similar goods/services.

And while I would argue that existing trademark law is capable of protecting trademarks in the virtual world, the rise of the metaverse and things like NFTs is, nonetheless, starting to pit brands against makers of NFTs with increased frequency, and raising some compelling questions – from how far companies’ existing trademark rights extend to new technologies to what infringement (and secondary liability for marketplace platforms) might look like.

Virtual Trademarks

As I addressed in a recent article about the MetaBirkins, one question that immediately stands out is the extent to which brands have the requisite trademark rights to successfully claim infringement or dilution in connection with virtual goods/services if they are not actually operating in the metaverse, themselves. Trademark rights, including the right to stomp out infringement, are generally amassed via use of a mark in certain classes of goods or services. Yet, it may not be a deal-breaker that Olive Garden or Hermès do not exist in the metaverse (yet), as a trademark holder may successfully halt unauthorized uses of its mark even if the allegedly infringing mark is not being used on identical – or in some cases, even competing – goods and services. After all, trademark holders can legally prevent others from using their mark or a mark that is similar to theirs on “related goods or services.”

Reflecting on the Non-Fungible Olive Gardens NFTs, trademark attorney Ed Timberlake recently stated that given the similarity between the Olive Garden and Non-Fungible Olive Gardens marks, it is “easy to imagine that restaurant services and whatever we want to call what is going on in the metaverse would be related, especially since we know that plenty of owners of federal trademark registrations for services in the non-metaverse are applying to register the same marks for use in the metaverse.”

Brands v. NFTs: Use in Commerce & Confusion

Beyond that, and assuming that there are enforceable trademark rights at play, there is the question of infringement. In order to prevail on a claim of trademark infringement, a plaintiff need not only establish that it has a valid mark; it must establish that the defendant has used the same mark or a similar mark in commerce in connection with the sale or advertising of goods or services without its consent. In the context of the sale of NFTs, such as 100 MetaBirkins or nearly 900 Olive Garden outposts, the commercial element seems relatively obvious: it is the offering up and sale of these NFTs.

(Even if these NFTs were offered up for free, they could still undercut another party’s market for the goods/services at issue. That is what Candidus Dougherty and Greg Lastowka argued in their 2008 paper, Virtual Trademarks, stating that “even activities intended as non-commercial could fall within the jurisdictional reach of the Lanham Act.” In other words, the unauthorized distribution of virtual swoosh-bearing sneakers, for instance, “even if done for free, could undercut [Nike’s] market for virtual sneakers.”)

Is There a Likelihood of Confusion?

The commercial nature of such NFTs is only part of the equation here, as a trademark holder plaintiff would also need to establish that there is a likelihood of confusion in order to make a trademark infringement case. This is established by way of a number of factors, which generally include: (1) the strength of the plaintiff’s mark; (2) the degree of similarity between the two marks; (3) the proximity of the products; (4) the likelihood that the owner will bridge the gap/expand its product lines; (5) evidence of actual confusion; (6) defendant’s intent in adopting the mark; (7) the quality of defendant’s product; and (8) the sophistication of the consumers.

Staying with the example of virtual swoosh-bearing sneakers, proposed by Dougherty and Lastowka, an example that could also apply, for example, to NFTs tied to depictions of swoosh-bearing sneakers, the first factor is something of a no-brainer, as Nike’s name and swoosh logo are a couple of the most famous marks in the market, and certainly, among the most famous in the sportswear segment.

Assuming that the unaffiliated virtual sneakers bear a swoosh logo or a reproduction of the Nike word mark, then the second factor, the degree of similarity between the two marks (in sight, sound and meaning), would weigh in Nike’s favor, as well.

The proximity of the products – which considers whether the products are complementary, sold to the same class of purchasers, and similar in use and function – is a particularly interesting factor in the context of the metaverse and things like NFTs. While physical sneakers versus those that exist exclusively in a digital capacity maintain obvious differences, primarily in terms of their medium, there is an argument to be made about similarly when it comes to the role that trademarks play in both the tangible and virtual worlds.

In many ways, just as brands’ logos are capable of indicating source in the “real” world, they may also communicate a physical wearer’s values as a result of the goodwill embodied in those logos (which is part of what serves to drive up margins for brands’ trademark-bearing offerings). At the same time, though, trademarks likely function in the very same way no matter whether they are presented in a physical or virtual form. Nike’s marks, for example, have meaning in the minds of consumers – and thus, have status-signifying or community-indicating power – when they appear on physical products. This core messaging does not change if the trademarks appear in virtual form.

In addition to part of the underlying function of trademark-bearing goods being the same no matter the medium, Dougherty and Lastowka assert that it is also “possible to view the virtual sneakers as complementary products to or marketed to the same class of consumers as the real sneakers.” For example, they state that “virtual world users who wear Nike apparel in real life would probably be more likely to purchase such apparel [or footwear] for their avatars.” As such, while “the products are [technically] very different, the consumers purchasing the products could be the same, which would increase the risk of association.”

In terms of the trademark holder’s likelihood of expansion of its product lines, this is another intriguing factor and one that seems as of now to weigh heavily in favor of trademark holders given the number and the range of brands that actually are operating in the virtual world via gaming, AR/VR, NFTs, and so on, or that appear to be eying expansion into this space based on the swiftly growing number of intent-to-use trademark filings.

Still yet, evidence of actual confusion is highly fact specific, as is a defendant’s intent in adopting a certain mark. However, in instances where a defendant knowingly makes use of an exact (or near exact) replica of another’s mark, that may strongly suggest an intent to derive benefit from the reputation of the plaintiff’s mark.

The final two factors are similarly worthy of attention. The quality of defendant’s product is a factor that does not necessarily translate neatly from physical goods to virtual ones. “What constitutes quality with regard to a virtual sneaker? Can a virtual sneaker have material qualities that are only revealed after purchase?,” Dougherty and Lastowka ask. Given the difficulty that comes with gauging the quality of an intangible product and then comparing that quality to the quality of a tangible product, what might be a more apt approach is a consideration of the defendants’ online services versus those of the trademark holder.

It might be more reasonable to try compare the services or experience provided to consumers by Nike via its authorized Nikeland experience in Roblox, for example, versus whatever the buying experience offered up by the defendant entails. But even that feels like a bit of a stretch, which may be a testament to the fact that existing legal doctrines and the corresponding standards are not always perfectly suited for novel technologies.

Finally, there is the sophistication of the consumers and the level of attention/care exercised, which could vary significantly depending on the product. Consumers shelling out upwards of $200,000 for a Bored Ape Yacht Club NFT are arguably both sophisticated and exercising a degree of care that patently differs than when someone is spending $17 for a virtual Gucci sneaker.

Going Forward

Brands are currently weighing the merits of operating in the metaverse, and it is entirely unsurprising that some are a bit more hesitant (and defensive) than others. Putting aside the strength of any potential legal action, the response by many fashion and particularly, luxury players will likely mirror the way that they have responded to other developments that have come before the mainstreaming of NFTs. In other words, should the metaverse turn out to enjoy the $1 trillion market valuation that is currently being projected, the industry’s biggest brands will almost certainly follow the roadmap set out in connection with things like the adoption of e-commerce, the evolution of licensing, or the rise of the resale market.

Some brands will undoubtedly look to own the space and respond to unauthorized endeavors with legal action. Chanel’s lawsuits over the resale market come to mind. Meanwhile, in much the same way as companies have responded to the enduring demand for pre-owned goods and omnichannel retail experiences, others will opt to engage but aim to do so by bringing their virtual operations as close to home as possible – either via in-house operations (i.e., Balenciaga’s digital arm and OTB’s new metaverse division) or joint ventures or partnerships (think: Nike and Roblox or Gucci and Roblox) – in order to exert a certain level control over the market of virtual goods bearing their trademarks and the conditions in which these goods are offered up.

It is certainly still very early days when it comes to the metaverse and corresponding technologies, but either way, as more unauthorized uses come to light, it will not be surprising if otherwise skeptical or hesitant brands opt to enter in metaverse ventures with the aim of amassing stronger rights in their valuable assets and thus, more easily stomp out infringements and control over their images.