Deep Dives

“Versace will debut a new pattern for clothes, handbags and other products” at its upcoming fashion show in March, one that “executives believe can singlehandedly rejuvenate the Capri Holdings-owned label as the luxury market looks to recover from a pandemic-fueled decline,” Bloomberg reported this month, citing Capri CEO John Idol, who stated on a Q3 earnings call that the new foundational pattern is expected “to change the trajectory of the company significantly over the next 24 months.”

Mr. Idol revealed that creative director “Donatella Versace’s design vision and her marketing prowess are working exactly the way that we had envisioned when we acquired the company” in 2018 for $2.1 billion. However, the Gianni Versace-founded brand is seemingly still in need of – and in the process of building out – a solid “base,” according to the group’s CEO, to bolster its “portfolio of recognizable, iconic products.”

A successful rollout of a proprietary new print “will improve the profitability dramatically for Versace,” Idol asserted on the recent conference call, noting that such critical source-identifying assets are something that Versace has been missing “compared to our luxury peers,” such as powerhouses like Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Chanel, and Prada, which have robust arsenals of thoroughly-monetizable (and legally-protected) branding elements as their disposal.

Versace has, of course, not been without such assets. As the company’s former worldwide head of marketing Lorenzo Conti stated in a 2018 deposition in a Versace trademark case, “For nearly four decades, Versace has marketed its products under the Versace name using a family of distinctive trademarks,” its Barocco pattern included, which he said he enabled Versace to “build a luxury brand that is widely recognized worldwide for glamorous and provocative designs, the finest quality and craftsmanship, and exclusivity.”

But while the Versace name and its black-and-gold Barocco print have helped to create brand awareness and sales for Versace for decades, from a brand asset perspective, Versace has routinely ranked lower than its high fashion/luxury peers in recent years when it comes to “brand value” – or what London-based business valuation consultancy Brand Finance defines as “the value of the names, terms, signs, symbols, logos, and designs” that a company uses to identify and distinguish its “goods, services or entities” from those of others.

For instance, the brand landed in the number 42 spot (up from 44 the year prior) on Brand Finance’s “Italy 50” 2020 report, a list that ranks Italian brands by the value of their intangible assets. On that same list, which included both fashion and non-fashion names, Gucci took the top spot in 2020, Armani came in at number 11, LVMH-owned Bulgari ranked at 12, and Moncler at 17. In the number 42 position, Versace ranked lowest of all fashion names.

Compared to all of its luxury and premium peers regardless of nationality, as represented on Brand Finance’s 2020 “Luxury & Premium 50” list, Versace ranked in at 40 out of 50, the same position it held the year before. (For a point of comparison, driving a top-10 ranking for Ferrari, for example, Brand Finance stated that in a testament to goodwill of the brand, as embodied in its source-identifying assets, “It is no wonder that many consumers, who might never own a Ferrari car, want a bag or a watch emblazoned with the Prancing Horse [logo].”)

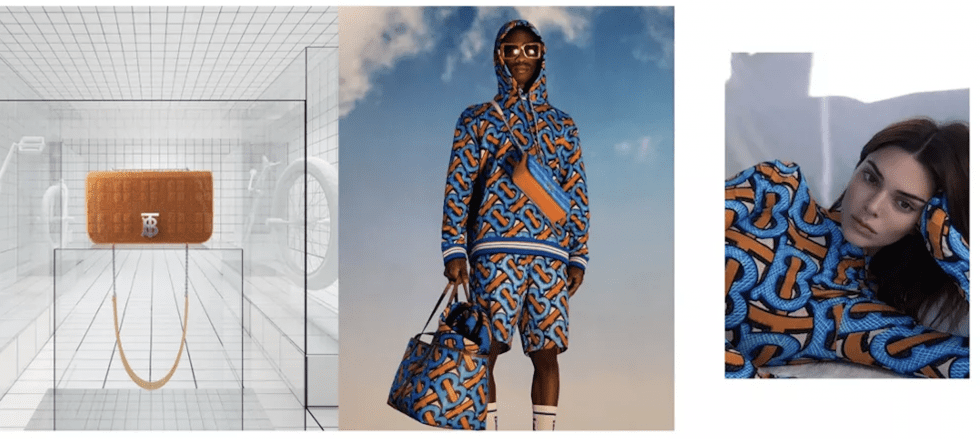

The path that Versace is taking is certainly not uncharted. Distinctive monograms have proven an effective asset for the likes of Louis Vuitton, Dior, Goyard, and Gucci, for example, which have maintained signature patterns for several decades – or longer. More recently, under the watch of Riccardo Tisci, Burberry rolled out a pattern of its own, the TB Monogram, in furtherance of a similar quest to reinvigorate the brand and boost brand awareness among new – and existing – customers, and ideally, generate better margins.

As of July 2019, Burberry reported that Tisci’s designs had helped increase revenues, enabling the brand to beat analysts’ expectations. The British fashion company saw a 4 percent increase in sales for the three-month period through June, which was the first quarter where there was a “meaningful” amount of new product from Tisci in stores. Burberry’s chief financial and operating officer Julie Brown revealed that monogrammed garments and accessories, in particular, had been a hit among Chinese millennials, with sales in China up by double-digits during the three-month period.

Bloomberg reported at the time that Tisci had “marked his arrival at Burberry by plastering a flashy new monogram print across store fronts and billboards, and on products including duffel bags, high-heeled shoes and trench coats in a bid to compete with logo-focused labels like LVMH flagship Louis Vuitton.”

And for good reason. Bloomberg’s Kim Bhasin aptly noted this month that in addition to “defin[ing] high-end brands,” high fashion and luxury goods companies’ source-identifying prints can “have a direct impact on sales,” with logo-emblazoned goods – from handbags and t-shirts to eyewear and footwear – enabling brands to achieve the high margins and high-volume turnover that their runway offerings lack. Echoing this well-established sentiment, luxury goods consultant Robert Burke says that there is “great value from a margins standpoint from logos for a brand, [as] the price ratio on a product goes up with a logo on it.”

And that is not expected to change due to the enduring impacts of the pandemic. Unlike in the wake of the 2007-2008 financial crisis, when brands fared well by shunning logos and other demonstrations of conspicuous consumption, some consumers may opt for less logo-centric wares post-Covid, but that will not be the case across the board. Boston Consulting Group has stated that coveted Chinese consumers, for example, “continue to prefer luxury items with embellishments, logos, and other visible adornments,” even in the wake of the pandemic.

With that in mind, and if Capri’s plan to aggressively boost Versace revenues, is any indication, an injection of new assets will certainly be a welcome – and likely, necessary – addition to the foundation of the Italian brand. As such, 43-year-old Versace is looking to “find a new hit design to follow the Barocco [pattern] that it has replicated across clothes, handbags, shoes, belts and jewelry” since it was first introduced by the brand in the late 1980s.