BAPE cannot escape the trademark lawsuit that Nike lodged against it over its “escalating infringement” of some of Nike’s most well-known sneaker designs. On the heels of BAPE seeking an early escape from Nike’s infringement and dilution claims, arguing that Nike has failed to adequately identify the elements of its sneaker trade dress, Judge Paul Gardephe of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York refused to grant the Nigo-founded brand’s motion to dismiss. The judge held that while the court is not ready to rule on whether Nike has met its burden of establishing the elements of its trade dress, it did shed light on the important – and often contentious – issue of what is (and is not) required of a plaintiff when it comes to pleading its trade dress.

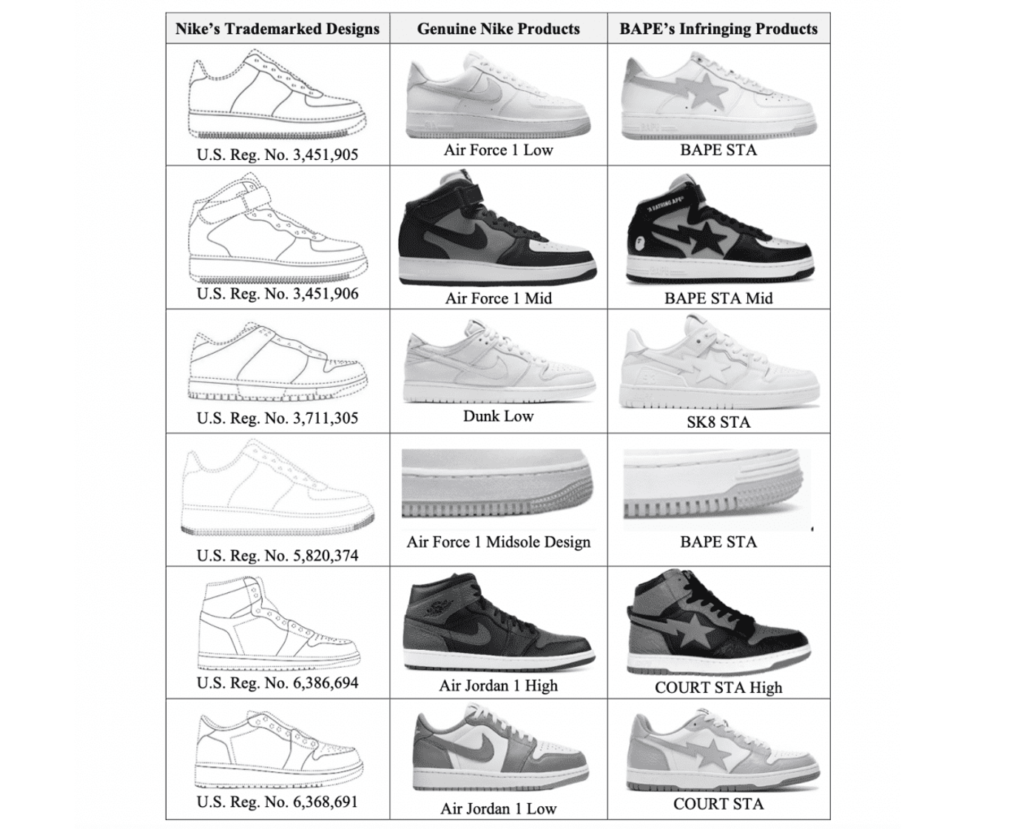

Some background: Nike filed suit against BAPE in January 2023, alleging that while BAPE first introduced infringing footwear in the U.S. in 2005, for most of that time, BAPE’s infringement was “de minimis and inconsistent,” and thus, did not warrant litigation. It was not until 2021 that the company began to escalate its infringement scheme, prompting Nike to wage trademark claims on the basis that BAPE sneakers infringe its Air Force 1, Air Jordan 1, and Dunk sneaker designs, according to Nike.

Delving into the critical issue at play, whether Nike has sufficiently articulated the elements of its various sneaker trade dress, Judge Gardephe considered both parties’ arguments as to the relevant standard.

> BAPE “contends that ‘the standard for pleading trade dress protection is particularly high for product configuration trade dress’ and that ‘Nike’s allegations in the complaint fall short of what is required for a cognizable trade dress claim,’” the court stated. Because Nike relies exclusively on “the [trade dress] registration numbers, the drawings attached to the asserted registrations, and photographs containing images of certain shoes allegedly bearing the [allegedly infringed] trade dress,” BAPE claims that it “has failed to identify ‘which of the trade design elements are distinctive and how they are distinctive.’”

> Nike, on the other hand, argues that it is not required to plead the specific elements of its trade dress that are distinctive and how they are distinctive, as the heightened pleading standard only applies to trade dress that has not been registered, which is not the case here.

Trade dress case law: Turning its attention to BAPE’s argument that Nike’s complaint is deficient even if it has registrations for the sneakers’ trade dress, the court states that BAPE relies on two cases: E. Remy Martin & Co. v. Sire Spirits, 21 Civ. 6838 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 10, 2022) and Heller Inc. v. Design Within Reach, 09 Civ. 1909 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 14, 2009).

In E. Remy Martin, a case over the design of liquor bottles, the court granted the defendant’s motion to dismiss after finding that although plaintiff’s marks were registered, the complaint was nonetheless deficient because it did not provide “a list of clearly and separately identified elements [of the trade dress]” entitled to protection.

Meanwhile, in Heller case, which centered on the alleged infringement of the design of two chairs, the court rejected the plaintiff’s attempt to rely on the images of the chairs attached to the complaint (in addition to “vague description of its claimed trade dress as an ‘ornamental and sculptural chair’”), arguing that they “provide the most precise definition of the trade dress possible.” The court found that the plaintiff had not provided “any written description of its protected trade dress” and that “images alone do not satisfy [its] obligation to articulate the distinctive features of the trade dress.”

Judge Gardephe also noted that the court in Heller also rejected plaintiff’s argument that as a result of its registration it was not required to list the protectible elements of its trade dress.

In his March 4 order, Judge Gardephe said the court would decline to follow either of those cases “to the extent that they hold that the owner of a registered mark is obligated to plead facts showing that their trade dress is protectable under the Lanham Act,” as the “Second Circuit and numerous courts in this District have repeatedly held that registration creates a presumption of protectability as to … scope, distinctiveness, and secondary meaning.” He also pointed to a recent finding in a trademark case waged by Nike, in which an SDNY judge denied a motion to dismiss premised on the same argument that BAPE makes here, finding that Nike “satisfied the first prong of the infringement test by registering its trade dress with the USPTO and attaching the certificates of registration to the complaint.”

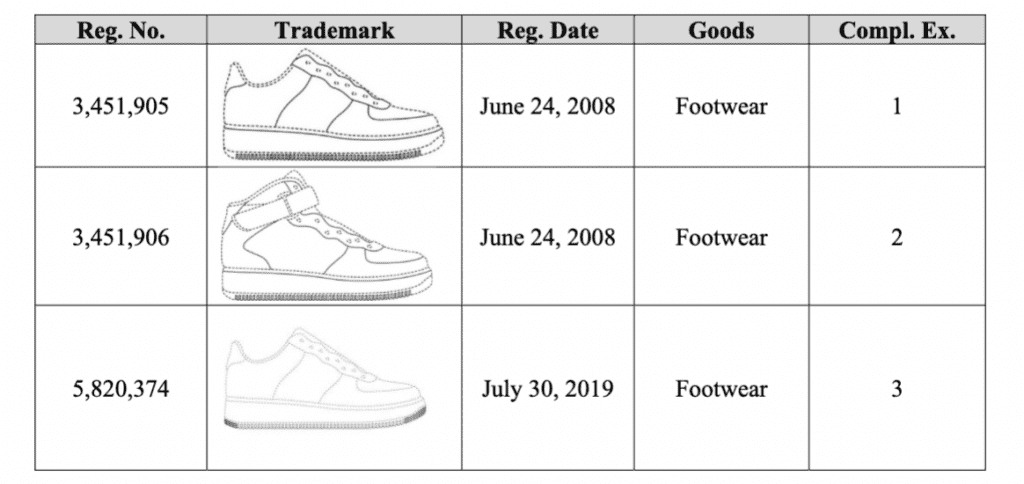

TLDR: “Nike’s certificates of registration, as incorporated in the complaint, adequately articulate the scope of Nike’s asserted trade dress,” per Judge Gardephe, as they “contain detailed written descriptions as well as diagrams that specifically denote which parts of the trade dress are being claimed as distinctive.” And while BAPE argues that “three of the six descriptions are completely identical, and two of the other three are nearly identical, the diagrams of the trade dress are sufficient to identify the scope of the trade dress that is being claimed as distinctive.”

With the foregoing in mind, the court said that it is “not prepared to rule that Nike’s written descriptions and trade dress diagrams are insufficient articulations of ‘the specific elements of the trade dress that should be protected.’”

THE TAKEAWAY: The court’s order is noteworthy in light of enduring ambiguities when it comes to the articulation of the trade dress. “Even armed with knowledge of the legal test for trade dress validity, it can be a challenge to articulate precisely which aspects of a company’s myriad and often complex designs constitute the company’s trade dress,” as Foley & Lardner’s Jean-Paul Ciardullo previously put it. He notes that trade dress plaintiffs typically face two pitfalls: “(1) the failure to define which particular combination of elements of a design are protectable; and (2) the failure to identify a specific universe of accused infringing designs.” This order and others like it should provide some additional insight for parties looking to wage (and defend against) often less-than-straightforward trade dress infringement claims.

The case is Nike, Inc. v. USAPE LLC, 1:23-cv-00660 (SDNY).