In February 2019, Daniel Lee sent his first main season collection down the runway in Milan. Among leather shift dresses, quilted leather puffer jackets, moto leather trousers, and a mix of vibrant knitwear, a wavey-shaped handbag in a green hue was tucked under the arm of a catwalker. What was little more than a passing accessory at the time, the bag was – in hindsight – an indicator of what was to come, albeit not so much from a design perspective but a branding one. In many collections since then, Mr. Lee has included “it” accessories, as well as apparel, in the same color, revamped its packaging to include the green, and also put the specific shade at the center of many of its retail outposts and pop-up installations, prompting the fashion press and consumers, alike, to begin referring to it as “Bottega Veneta Green” or simply, “Bottega Green.”

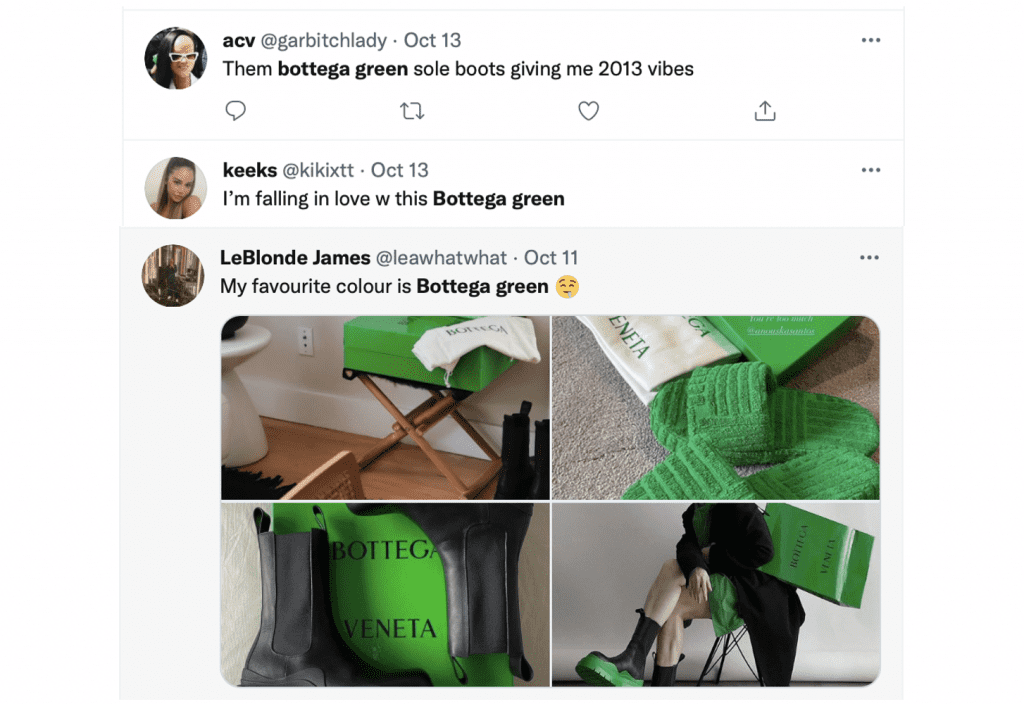

The potential for “Bottega Green” to serve as an indication of source when used on apparel and/or accessories in something of the same way as the Bottega Veneta name, for instance, is worth pondering given the rate at which consumers have come to connect – name-check – the brand in connection with the color. And it would not be the first time that a brand has been able to show that consumers link a specific use of a specific color to a single source.

Most commonly, this sees brands amassing (and enforcing) rights in the use of a specific color for their packaging. Hermès’ orange comes to mind, as does Tiffany & Co. blue, Glossier’s pink, and Cartier’s red. Seemingly less common (but certainly not unheard of) is the existence of trademark rights in a color for use on products, themselves. The most famous fashion industry example is, of course, Louboutin’s rights in “Chinese red” for use on the soles of contrasting color footwear.

The ability of brands to rely on trademark protection – a form of intellectual property protection that applies to “any word, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof” that is used to “identify and distinguish” one’s goods or services from those of others – when it comes to colors is not a novel phenomenon. Colors are not included within the statutory definition of trademarks, but the U.S. Supreme Court put any doubts to rest about their protectability in 1995 when it decided Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co., a landmark case that centered on the green-gold color of Qualitex’s dry cleaning press pads. In its decision, the Supreme Court explicitly stated that a color can be registered as a trademark, assuming, of course, that it identifies a single source for the goods/services at issue.

As Cooley’s John Crittenden and Bobby Ghajar asserted in a note last year, color marks have “a long and complex history under U.S. trademark law,” with certain brands being instantly associated with a specific color, such as Tiffany blue or pink fiberglass insulation.” However, just because colors can act – and be protected – as trademarks does not mean that all (or even many) uses of color by brands amount to trademark uses, as most companies “use colors as ornamentation [or decoration], rather than to signal the source of the product,” Crittenden and Ghajar assert.

Aside from potentially being inherently decorative in nature (and not functioning as a trademark as a result), colors can take on a non-source identifying role if they are “functional or utilitarian, such as colors that are used to indicate the flavor of a product (red for cherry) or allow the product to blend in better with its surroundings (camouflage for hunting gear).” Purely ornamental or functional/utilitarian use stands in the way of a color serving as a trademark, as in order to function as a mark, the color needs to identify a product or service’s source in the minds of consumers, rather than serving some other purpose.

And still yet, it is worth noting that should a brand seek to claim rights in (and amass registrations for) the use of a color mark, in addition to establishing that the mark is not being used in a purely decorative or a functional capacity, it would generally need to show that the mark signifies to consumers that a product comes from a single source. In other words, a company must “cultivate consumer recognition of the particular color as an identifier of source,” per Debevoise attorneys Megan Bannigan, Christopher Ford, and Kate Saba, which can be achieved by a brand “advertising and promoting the color as its trademark, and sold products and services bearing that color for a substantial period of time, such that the color acquired distinctiveness.”

What does all of this mean for Bottega Veneta, which has been utilizing Kelly green on its packaging and products and in its retail outposts with increasing frequency and consistency as of late? It may mean that the Kering-owned brand is well on its way to amassing exclusive – but limited – rights in the hue (one that is not earth-shatteringly novel but also not a terribly common shade for luxury brand packaging or for handbags, footwear, etc., either).

“The fact that the Bottega green color is not a shade one encounters on these particular items every day, combined with how often that color-product-source cluster is repeated, tends to make me think more than a few people are already making [a] cognitive connection” between the color and the brand, which, trademark practitioner and former USPTO examining attorney Ed Timberlake says is at the very core of the secondary meaning/consumer recognition equation.

It also bodes well for Bottega that the realm of relevant subject matter when it comes to trademark law is “vast,” and tends to be “categorically non-categorical,” Timberlake says; the pool of potentially protectable subject matter consists of “symbols,” regardless of whether those symbols be words, logos, designs, colors, etc. And “because the requirement for functioning as a symbol – which is basically that a human being able to attach some meaning to something – is essentially as broad as simply being perceivable (since we seem to be capable of attaching meaning to almost anything we can perceive),” he says that not very many things are really ruled out.

As for whether Bottega will have an easier time showing that consumers have come to associate “Bottega green” with its clothing and accessories or its packaging, Timberlake does not place much emphasis on this distinction, stating that “the kinds of things that might influence whether a connection is made between stimuli and a product has less to do with the categorical distinction – such as packaging vs. product, or color vs. text – and more to do with how unusual the stimulus is in that context.” Also telling is “how often the exposure is repeated.”

For a “very mildly unusual color on a particular product,” such a Kelly green used on leather handbags, he says that “it might take 1000 repetitions before people start to make the connection, whereas with a very unusual color in a specific context it might only take a handful of repetitions.”

As of now, Bottega Veneta has not sought to register its green in connection with any marks, but that does not mean, of course, that it is not accumulating rights anyway by virtue of its use of the color on certain goods/services ahead of potentially seeking registrations at a later date. It is also worth noting that the brand is no stranger to amassing registrations for slightly-more-difficult to claim marks, including for its weave design (i.e., “a configuration of slim, uniformly-sized strips of leather, ranging from 8 to 12 millimeters in width, interlaced to form a repeating plain or basket weave pattern placed at a 45-degree angle over all or substantially all of the goods”).

Beginning in 2007. counsel for the brand sought to register the weave design for use on leather goods, including handbags, in the U.S., and ultimately, was able to overcome pushback from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”), including on aesthetic functionality and non-distinctiveness grounds, which ultimately registered the design in 2014 in a widely-reported development that was touted as shedding light on the scope of trademark rights in the U.S.

Among other things, Bottega argued – and the USPTO’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Board agreed – that the weave design was not merely ornamental, but rather it functions as a trademark to indicate the source of the goods as a result of consistent use of the mark, upwards of $18 million in advertising spend between 2001 and 2007, and U.S. sales of more than $275 million sales during that same period, with more than 80 percent of those sales consisting of goods sold that included the weave pattern.

Chances are, Bottega could – and very likely will (at some point down the road) – make similar arguments about the function of its green hue.