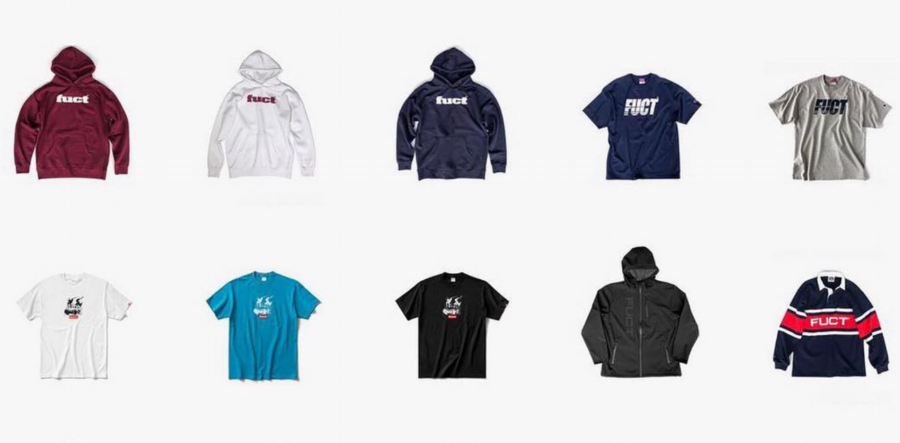

Fuct. More than merely the name of the cult-followed brand that Erik Brunetti founded in Los Angeles in 1990 alongside then-partner, professional skateboarder Natas Kaupas, the word – which Mr. Brunetti says “can pronounced ‘fucked’ and at the same time, [serves as] an acronym for Friends You Can’t Trust” – is at the center of a case set to be reviewed by the highest court of the U.S. On Monday, the nine Supreme Court Justices will hear arguments in the case, Andrei Iancu v. Erik Brunetti, in which the key question at issue is whether a trademark – such as “fuct” – can be refused registration because it is “immoral” or “scandalous.”

When Brunetti first attempted to register the name of his famed streetwear-slash-skatewear brand – in 2011, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) had one word for him: no. As Mr. Brunetti would soon learn the hard way, the USPTO, as the arbitrator of federal trademark registrations in the United States, has the authority to bar the registration of names, logos and other trademarks that it deems to be “immoral” or “scandalous.” In the eyes of the USPTO, “fuct” – the name of Mr. Brunetti’s brand – fit squarely within this territory.

From the outset the name of Brunetti’s brand – which he founded in Los Angeles in 1990 alongside then-partner, professional skateboarder Natas Kaupas – was something different, “something that wasn’t on the market.” In fact, the name, itself, was an entirely new word, something that would traditionally bode well for trademark protection. “It would be pronounced ‘fucked’ and at the same time it’d become an acronym for Friends You Can’t Trust,” Brunetti said in an interview with Godhood years later.

That name – and an attempt to secure sweeping federal rights in it for use on apparel (to coincide with the state law rights Brunetti had already amassed by using the mark on his products throughout the country)– is what would land Brunetti in front of trademark bodies and one court after another more than 20 years after his brand first rose to fame and achieved cult-like status.

You see, just as the Trademark Trial and Appeals Board was agreeing with the USPTO examiner’s decision that “fuct” could not be registered because it is “immoral” or “scandalous,” and refused to register Brunetti’s mark, an interesting case – Matal v. Tam, which centered on an Asian-American brand called, The Slants – was making its way through the court system.

In June 2017, the Supreme Court issued a unanimous decision in favor of The Slants. To be exact, America’s highest court held that the Lanham Act’s Disparagement Clause – the provision that prohibits the registration of trademarks that would serve to “disparage … persons, living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, or bring them into contempt, or disrepute” – violates the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment, which prevents Congress from making any law, including potentially, the Lanham Act, that prohibits the free exercise of speech.

The ruling meant that Simon Tam and the other members of The Slants could not legally be barred from obtaining federal trademark protection due to the nature of their band name. It also meant that Brunetti’s luck would change.

As 2017 was close to coming to an end, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, having taken up Brunetti’s appeal of the Trademark Trial and Appeals Board’s decision to reject his trademark, cited the Supreme Court’s ruling in The Slants case, and handed Brunetti a win.

According to the Judge Kimberly Moore, writing for the Federal Circuit’s three-judge panel, fuct – which is the “past tense [version] of the verb ‘fuck,’ a vulgar word” – is, in fact, “scandalous.” However, Judge Moore stated that the First Amendment “protects private expression, even private expression which is offensive to a substantial composite of the general public,” and such protection extends to the fuct mark.

Brunetti walked away with a win.

However, his triumph could potentially be short-lived, as the Supreme Court agreed on Friday to review the Federal Circuit’s decision, after the USPTO’s formally requested that the Supreme Court take on the case. At issue, according to the petition filed on behalf of Andrei Iancu, the Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and the Director of the USPTO in September, is whether the Lanham Act’s prohibition on the federal registration of “immoral” or “scandalous” marks is facially invalid (i.e., unconstitutional) under the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.

According to the USPTO’s petition, the lower court erred in siding with Brunetti. In the 73-page filing, the USPTO argues that the Lanham Act’s ban on the registration of scandalous marks does not run afoul of the First Amendment because it does not restrict what may be used as trademarks, only what may be registered. In other words, the USPTO may refuse to register a mark (in accordance with the Lanham Act ban) but even then, it does not prevent the trademark application filing party’s use of that mark.

In the U.S. (and other jurisdictions that award trademark rights to parties that are the first-to-use a specific trademark), rights are not gained by way of a registration with the USPTO but through actual and consistent use of the mark on commerce. This means that even if Brunetti (or any other party for that matter) does not register his mark with the USPTO, he still maintains common law (i.e., state law) trademark rights, which he can assert against parties that are using his mark without authorization.

The 100-year old ban on the registration of “immoral” or “scandalous” marks “simply reflects Congress’s judgment that the federal government should not affirmatively promote the use of graphic sexual images and vulgar terms by granting them the benefits of registration,” U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco argued in the USPTO’s petition.

As for Brunetti, he is hardly staying silent. “The scandalous clause is not a content-neutral rule that rejects all profanity, excretory and sexual content,” he has asserted in connection with the Langham Act provision. “Instead, the government is selectively approving or refusing profanity, excretory and sexual content based upon the level of perceived offensiveness.”

His scandalously named brand will have its day in court o n Monday, with a decision from the court expected before July.

*The case is ANDREI IANCU v. ERIK BRUNETTI, 18-302 (SCOTUS).

This article was originally published in January 2019, and has been slightly updated exclusively to note SCOTUS’ hearing on Monday.