About a year ago, on February 14, 2013, Tiffany & Co. filed suit against Costco in New York federal court. The discount retailer, according to Tiffany’s complaint, was selling counterfeit engagement rings. The jeweler alleged that Costco was confusing consumers into thinking they were getting a Tiffany product by displaying signs in a Huntington Beach, California store that used the word “Tiffany” to describe rings being sold. Tiffany owns many trademarks related to jewelry, and the thought of consumers believing they could buy such an iconic product at Costco was definitely concerning, so it was not surprising to hear that Tiffany was more than just a little displeased. We’re here to tell you all about how the case has progressed, i.e. the very interesting back and forth between Costco and Tiffany, since last February.

Here are some of the highlights from Tiffany’s original complaint (which alleged Costco was guilty of trademark infringement, dilution, counterfeiting, unfair competition, injury to business reputation, false and deceptive business practices and false advertising): the high-end jeweler pointed out that Costco does sell branded jewelry, like Cartier, apparently, at a discount, which adds to the theory that consumers are likely to be confused; Costco was not using the Tiffany trademarks online for the same products, allowing it to avoid “detection of unlawful activities by Tiffany’s normal trademark policing procedures”; Costco’s “no-frills” approach to retailing is in stark contrast to the personalized attention offered at a Tiffany store; and “Costco knowingly, intentionally and willfully used the Tiffany Trademarks to misrepresent the jewelry items described herein because they were far more valuable than its Kirkland Signature brand could ever be for jewelry items”.

Costco counterclaimed pretty quickly, and this is where things get really interesting. Costco claimed that the “word Tiffany is a generic term for ring settings comprising multiple slender prongs extending upward from a base to hold a single gemstone.” And in an effort to show that there was no intent to confuse consumers, Costco provided images of the unbranded, beige boxes that its rings were sold in, which are in no way similar to the iconic Tiffany Blue boxes that accompany a Tiffany purchase. Costco also relied on the so-called fair use defense from the Lanham Act in arguing that its use of the word Tiffany constitutes “use, otherwise than as a mark, … of a term … which is descriptive of and used fairly and in good faith only to describe” the ring settings. In other words, Costco is not using the word Tiffany as a trademark, but rather as a good faith description of a ring’s setting.

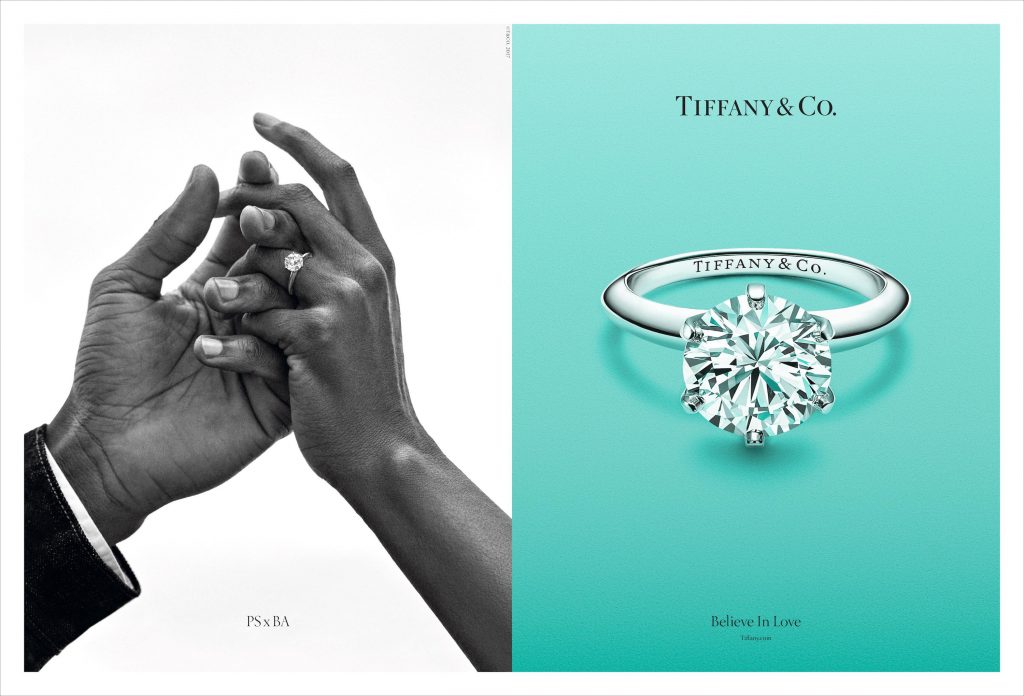

Within days, Tiffany filed a response, which stated that the phrase “Tiffany Setting” describes one thing and one thing only: a style of engagement ring designed by Charles Lewis Tiffany. In its response, the jeweler goes on to say, “a Tiffany Setting is only one that is manufactured and certified by Tiffany as being in accordance with Tiffany’s strict standards and specifications. It is available from only one place – Tiffany. Anything else is fake.”

Several other responses and motions have been filed by both Costco and Tiffany – including one in which Costco illustrated the idea that a trademark can become a generic term for a physical object by comparing the Tiffany setting to a Phillips screwdriver. But a recent federal court ruling on the issue has finally shed some light on how this may all end. And it doesn’t look good for Tiffany.

Southern District Judge Laura Taylor Swain denied Tiffany’s motion to dismiss Costco’s counterclaim on January 17. Judge Swain first pointed out that whether a mark has become generic is generally an issue of fact, meaning reserved for a jury to decide, and then went on to say that a jury may find that the term “Tiffany setting” is, in fact, generic. Judge Swain ruled that “[w]hile none of the evidence is by any means conclusive of the proposition advanced by Costco it is, taken together and read in the light most favorable to Costco in this pre-discovery context, sufficient to frame a genuine factual dispute as to whether the terms “Tiffany” and/or “Tiffany Setting” have a primarily generic meaning in the minds of members of the general public in the context of ring settings.”

That a Tiffany mark may be deemed generic, and therefore not protectable, is hard to swallow. But, all personal difficulty aside, in the eyes of the law, the Tiffany mark in the context of ring settings may very well be a victim of genericide. A Second Circuit Court of Appeals decision explains genericism as follows: “[e]ssentially, a mark is generic if, in the mind of the purchasing public it does not distinguish products on the basis of source but rather refers to the type of product.” In accordance with the Lanham Act, the key determination to be made when determining if a mark has become generic is the significance of the mark to the relevant public: “The primary significance of the registered mark to the relevant public rather than purchaser motivation shall be the test for determining whether the registered mark has become the generic name of goods or services on or in connection with which it has been used.”